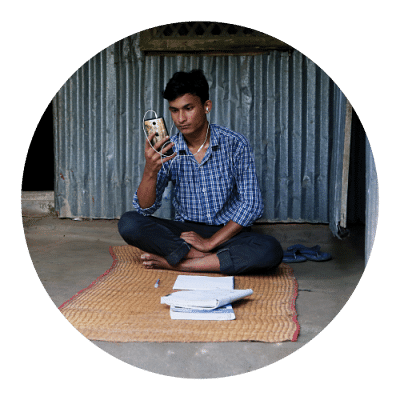

How students outside Dhaka miss out on opportunities

As much as we rant about how unlivable Dhaka city may be, most of us would blink in disbelief at the thought of having to move out. We are tied to this city — by obligations and attachments alike. Dhaka is so dense with opportunities that the opportunity cost of living outside it is disproportionately high. Take this from someone who has been incurring this cost for two decades.

I was doing a public speaking competition in 2018. While my competitors had to only think about preparing themselves, I had the extra headache of having to travel to Dhaka and arrange accommodation.

Despite the circumstances, I had been on the luckier side. I could at least attend the event. My parents always went out of their ways to support my extracurricular activities. This has not been the case for most of my peers living in Chattogram.

Days in school were pretty uneventful. Annual sports were held every winter. The only other competitions I remember are Olympiads and the Spelling Bee. These initiatives pooled participants from each district and then gradually funnelled them into the latter rounds, ensuring geographical inclusivity. Most other competitions made no significant effort to go beyond Dhaka.

The discrepancy was uncomfortably stark for Fahim Abrar Chowdhury, who had shifted to Chattogram after studying in Dhaka up to grade five. He recounted his days in Dhaka, where he was a member of his school's debate club. Their science club used to organise the biggest national science fair and other clubs kept the campus lively throughout the year.

"Shifting to Chattogram in class 6 felt like a drastic change," said Fahim. "ECAs mostly consisted of sports. The number of students interested in activities other than sports was very low and the institution did next to nothing to nurture the participants. There were no workshops for the debaters, in fact, there wasn't even a proper debate club until our time."

Most of my friends in Chattogram were completely deprived of such activities, as there is simply not much happening outside Dhaka.

Dhaka-centrism is a problem in almost all sectors in Bangladesh. But this discrepancy, especially when young people are involved, can run deeper to an unfair extent. It sets the stage for a gap that keeps widening over the years. Given the competitiveness drilled into our education and job sectors, people outside Dhaka are bound to have a hard time.

The harshest display of non-Dhaka residents having to walk the extra mile is during university admission when the stakes are much higher. Given the tremendous social pressure to get into a good university, many consider temporarily shifting to Dhaka for coaching. The trade-off is a tricky one — the proximity of good coaching institutions versus the convenience of taking preparation from the comfort of one's home. Either way, people outside Dhaka are forced to compromise.

The disadvantages of having grown up outside Dhaka trail behind even after getting into an institution in the capital. Non-Dhaka residents face difficulties when trying to find familiar faces in the capital. People residing in Dhaka end up finding a cohort of classmates and seniors they knew from before — either from school or debate or the MUN circuit. People from outside Dhaka are often left out from these groups and miss out on networking opportunities because of location barriers.

When Ipshita Maliat Rahman got into a business school in Dhaka, she didn't find anyone from her school, or even her town, Sylhet. "Most of the students in Sylhet don't want to go beyond medical and engineering," Ipshita said. Networking didn't happen as effortlessly for her as it did for most of her Dhaka-residing peers.

Having to move out of Dhaka after growing up there has its challenges, too. Fariha Sadek moved to Rajshahi to pursue her undergrad at Rajshahi University. The scarcity of opportunities makes her come back to Dhaka again and again, often at great inconvenience. For a case competition, she had to stay in the capital for thirteen consecutive days. The cost of doing one such competition is lost class attendance marks, missed content covered in those classes, with any possible quizzes or presentations held during that timeline. But the cost of living outside Dhaka doesn't end there.

"I tried to get a part-time job but couldn't because of my location disadvantage. Even organisations that allow remote work require employees at the office at least once a week," said Fariha.

I faced similar problems during my semester break. When the academic pressure finally let up and I felt like I had time to do other things, I was left with not many things to do because I went back home in Chattogram. Having to stay back in Dhaka — away from home even during semester breaks — to continue my part-time job seemed like stretching it too far. So, I took a break from work during a period when I actually had ample time to dedicate to it. Though I had a very good time with my family at home, I sort of felt like I was missing out. This wouldn't have happened had there been similar opportunities in my hometown too.

Thus, Dhaka keeps pulling us towards it. We have so many strings attached that being far gives a feeling of being detached or even abandoned. The missed opportunities become ghosts and haunt us. As a result, we make it a lifestyle to live with the constant fear of missing out.

Noushin Nuri is an early bird fighting the world to maintain her sleep schedule. She is on Instagram as @noushinnurii

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments