For Bangladeshi people, February 21 – Ekushey February – is a day of the year when national pride is at an all-time high. People wear black and white, and display their enthusiasm and love for our mother language.

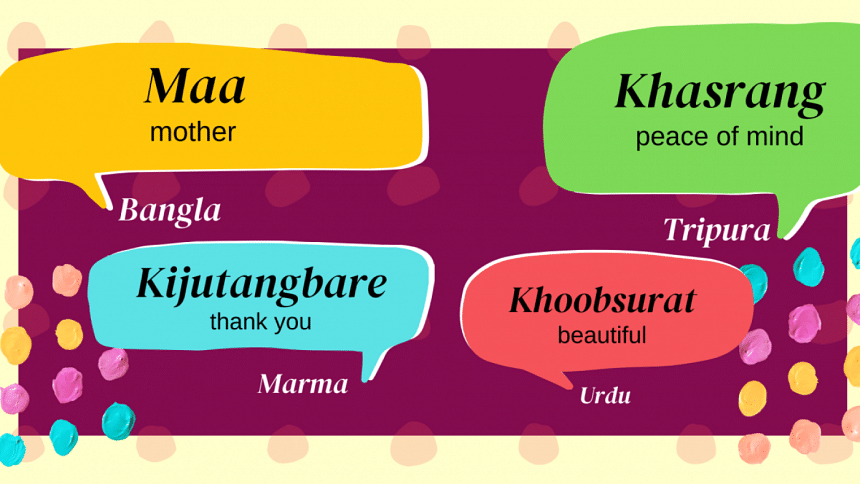

Under the semblance of ethnical homogeneity in Bangladesh, where Bangla is heralded as our national language, it is not always easily realised that the linguistic heritage of our country instead is varied, rich and diverse. Bangladesh is home to not one, but 41 different languages. Ubiy Prue Chowdhury, a 26-year-old teacher at the Vola Nath Para Government Primary School and a member of the Marma community, understands this perfectly.

"I speak only Marma, Chakma, and Bangla. I have students from the Tripura community who don't speak Bangla at all, and I don't speak Kokborok (language of Tripura people). I sometimes manage by communicating with them through their friends," she shares.

"When we were younger, schools didn't teach lessons in Marma," she recalls. "We were made to learn Bangla. There were people of different ethnicities in my neighbourhood so I learned Bangla from other children. Therefore, I didn't have a tough time learning Bangla at school. Interestingly, I had more issues learning Marma."

There are currently upwards of 1.5 lakh Marma speakers in Bangladesh, making it one of the major minority languages here. Although a Marma script exists, the language is mostly practised verbally.

"My grandfather can write Marma well, my father can speak well but not write it, I can only speak it," adds Ubiy. "We were never encouraged to learn Marma. The reasoning was that you study to get a job and you need Bangla for work. So, why learn Marma?"

Ubiy, however, agrees that the situation is changing now, saying, "Nowadays they do teach native languages at school. However, they only teach it in government schools in the towns. Kids who go to smaller or private schools in small communities and neighbourhoods aren't being taught their languages."

Despite there not being sufficient practice of Marma writing, Ubiy feels hopeful, "The Marma language is preserved well by our writers. As we have our own alphabet, we can use it to write about our own culture and history. Marma Unnayan Sangsad (MAUS) publishes many books to preserve our history and culture. But only a few people are doing this work."

The Chittagong Hill Tracts boast vibrant linguistic diversity as people from different indigenous communities hold on to their own cultures. However, the linguistic experience differs from one community to another, as, unlike Marma, not every language has its own script.

Bhuboneshwar Tripura is a final year university student in Dhaka. "Our language Kokborok is mostly passed down orally. We don't have any written form. This makes holding on to our language very difficult. Some people write Kokborok using Roman letters and some Indian states do have a written form, but not in Bangladesh," he says.

Growing up surrounded by other Bengali speaking families, Bhuboneshwar mostly acquired Kokborok and Bangla naturally, although not without glitches, "I speak Bangla fluently now. But when I was young, and even now sometimes, I face issues with pronunciation. I used to feel nervous and mispronounce words. Other kids in school would make fun of this."

Being mocked for her language is something Prachi Talukder, 23-year-old university student and a member of the Chakma community, shares experiences of. She says, "I grew up in Rangamati and there were many Bangla-speaking people around me so I kind of naturally learned Bangla. Before I was admitted to school, I was taught to write in Bangla from home."

"Sometimes when I speak in Bangla and I mispronounce or can't remember certain words, I receive negative attention and mean comments from people. It's not every day, but it does happen a lot. These instances make me feel a little isolated," Prachi adds.

Ubiy shares her sentiments, too. "Not everyone appreciates your culture," she comments.

Things have taken a positive turn for the Chakma language as awareness regarding language preservation is on the rise. Prachi explains, "When we were growing up, preservation of our mother tongue was not something people were aware of. Now, young people, especially, are contributing to preserving the Chakma language. Publications in Chakma language and representation through social media is also helping things change."

For indigenous people living in cities, Bangla is slowly taking over their own mother tongue. Such is the experience of Basil Kubi, who belongs to the Garo community. At home, Basil speaks in the Abeng version of Garo language, mostly popular in northern Bangladesh with about 1.25 lakh speakers.

"These days we are so used to speaking Bangla that even at home we mix up Bangla and Garo. Sometimes I can't remember certain words in my own language, but I remember them in Bangla. My friend circle mostly consists of Garo people, but we speak in Bangla among ourselves these days," Basil shares.

Apart from the gradual loss of spoken Garo, the written form of Garo language is also disappearing slowly. As Basil recounts, "We do not practice writing it at home or in the community. Even in villages, education is mostly given in Bangla; kids are not encouraged to learn writing in Garo. The Garo alphabet is mostly lost. Recently, the government has taken initiative to help primary students learn their mother tongue first. But for Garo children, they are mostly learning in Bangla."

The list of languages includes Khyang, Mru, Tanchangya, the ones spoken in the north west such as Santali and Kurukh, and those spoken in Sylhet region like Mon-khem. But there are speakers of other languages much closer to Dhaka.

Nahid Hassan, online entrepreneur and mother of two, recounts how language is a very important part of her family history. "Born in Pakistan, I came to Bangladesh in 1986 at the age of 9 or 10. I still speak to my parents in Urdu. Two of my sisters still live in Pakistan," she shares.

Nahid's journey learning Bangla while growing up largely revolved around her own choice, "It was very difficult for me to learn Bangla. My parents never forced us to learn anything. My chhoto chachi used to teach children so I saw her Adorsho Lipi (Bangla alphabet book) and was fascinated. There began my journey of learning Bangla."

But Nahid's connection to Bangla is more personal than that. "My father is Dhakaiya so I realised early on that Bangla is my father's language. My mother, however, is from Mumbai; she's a Memon."

For Md. Anisur Rahman, AutoCAD Designer at Integrated Design, learning Bangla was a natural process too. "When I first started working back in the 1990s, I was the only non-Bangla speaker in my office," he recalls.

"My father was a Sufi-like person who was obsessed with Urdu poets," Anisur says. "He used to speak Urdu. At home, I still speak in Urdu. However, after so many years, Bangla has become more prominent in my day-to-day life. I cannot write in Urdu, though. So, I generally just use it informally at home."

"As I grew up in Bangladesh, I have naturally picked up Bangla together with Urdu. I never felt any shame about it. In fact, I was always proud of knowing two languages where most people knew just one," Anis shares.

Celebrating International Mother Language Day, as a Bangladeshi, comes with recognising the cultural diversity within our own society. The stories of people from across our land reminds us of the many different languages Bangladeshi people call their own.

References

1. The Daily Star (February 22, 2019). Mapping our many mother tongues

2. The Daily Star (February 21, 2021). Dying in silence

Tazreen is a part time English major and full-time feminist attempting to be the 21st-century reincarnation of Judith Shakespeare. Reach her at [email protected]

Mrittika is a Sub-editor at SHOUT. Find her at [email protected]

Comments