The Universal Appeal of Pahela Baishakh

The Bengali calendar came into existence under the rule of Mughal Emperor Akbar. He realised that the fosholi shon or crop year was asynchronous with the Hijri or lunar year being followed to collect annual taxes from farmers. In the end, farmers were caught off-guard and obliged to make payments out of season. To address this problem, he came up with the idea of a calendar reform that would save the farmers from trouble. Commissioned by Akbar, the royal astronomer Fatehullah Shirazi formulated the said calendar by aligning the Islamic calendar with the harvest season.

After several adjustments made to the lunisolar calendar in 1966 by the Bangla Academy, this culminated in the bongabdo as we know it, where Pahela Baishakh recurs on April 14 every year in the Gregorian calendar.

What is seldom realised is that alongside the panta-ilish, mela, and Mongol Shobhajatra we indulge in, there are other South and Southeast Asian nations and even communities within Bangladesh celebrating the same lapse of a harvest season in concert.

Around the same time every year with Baishakh, takes place Boisabi, a three-day-long festival of indigenous communities in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The name is an acronym – a fusion of individual celebrations – Boishu of the Tripuras; Sangrai of the Marmas, Sankran of the Mros, Sangran of the Kyangs, Sankrai of the Khumis; and Biju of the Chakmas, and Bishu of the Tanchangyas.

Boisabi celebrations vary among ethnicities yet resemble in some ways. The Chakmas begin the first day of celebration, Phool Biju, by offering flowers in rivers and lakes early in the morning to seek blessings for the new year. In Mulbiju, the last day of Bengali month Chaitra, the aroma of pajon embraces the hills. Pajon is a special delicacy cooked with over 20 vegetables; some of which are seasonal. Although the more, the better. Goijja Pojjya Din, the last day of celebration and the first day of the new year is spent in prayer for yearlong peace and prosperity.

The Tripuras observe Boishu in two parts: Hariboishu, which is similar to Phool Biju; Bishima; and Bishikatal, the new year. On the other hand, Marmas solemnise the occasion in three days. They begin on the first day of Boishakh – Sangrai – followed by Sangrai Aika and Sangrai Atada. They engage in pani khela to wash away the sins of the past and start anew with this fun sport, and have their own treat, the Sangraimu, a form of traditional cake.

Despite the diversified customs and norms, these ethnicities have a shared goal to welcome the new year in the grandest way possible.

Incidentally in India, the Sikhs celebrate Vaisakhi, the traditional harvest festival, on April 13 and on April 14 after every 36 years. The day falls on Vaisakh, the second month of the Nanakshahi calendar followed in Sikhism. To the farmers, the new year starts as the crops are harvested. Main traditions include Awat Pauni where a hoard of people harvests the season's produce to the beat of drums. The day also holds divine significance and commemorates the formation of the Khalsa Panth by Guru Gobind Singh Ji in 1699. Large processions called Nagar Keertan are led. Like Bangladesh's red-and-white colour duo, people in various states of India clad in yellow and orange. Celebrations include prayers, baptism, bhangra, giddha, and many more.

Vishu, the Malayalam new year is celebrated in Kerala and other adjoining regions in Southern India. The prime custom is the Vishukkani (meaning "which is first seen on Vishu"), an arrangement of konna flowers, betel leaves, oil lamp, rice, lemon, cucumber, jackfruit, money, and image or statue of Hindu deity Lord Vishnu, and such. This is the "auspicious sight" that family members wake up to. It is a strong belief in the community that seeing something lucky will bring a good year. Time-honoured feast, sadhya, comprising a vast variety of dishes is served on betel leaves.

Puthandu Vazhthukkal! This means "happy new year" in Tamil. The morning begins with kanni, a ritual similar to Vishukkani, and the feasts are dominated by vegetables. In Sri Lanka, Aluth Avurudu bears a close semblance to Puthandu.

To the northeast, Assam loves to celebrate and is known for marking Bihu thrice a year, each celebrating a milestone in the crop year. Coincidentally, the Rongali or Bohag Bihu comes at this time of the year and is the biggest, most popular festivity of all that lasts a whole week. Assamese ethnic groups sing bihugeet, perform folk dances, and eat pitha and laru. In the same way, the people in Bihar rejoice Vaisakha twice a year; first in April and then in November.

The Nepalese boast a great number of festivities one of which is the Navavarsha. The day typically falls on the second week of April and is the first day of the Vikram Sambat calendar. The occasion is accompanied by Bisket Jatra (or the Festival of Bisket) in Bhaktapur. The event memorialises the battle of Mahabharata. A game of tug-of-war between residents from the lower part of Bhaktapur versus those from the upper part is played. The winning team is believed to be blessed with a great year ahead.

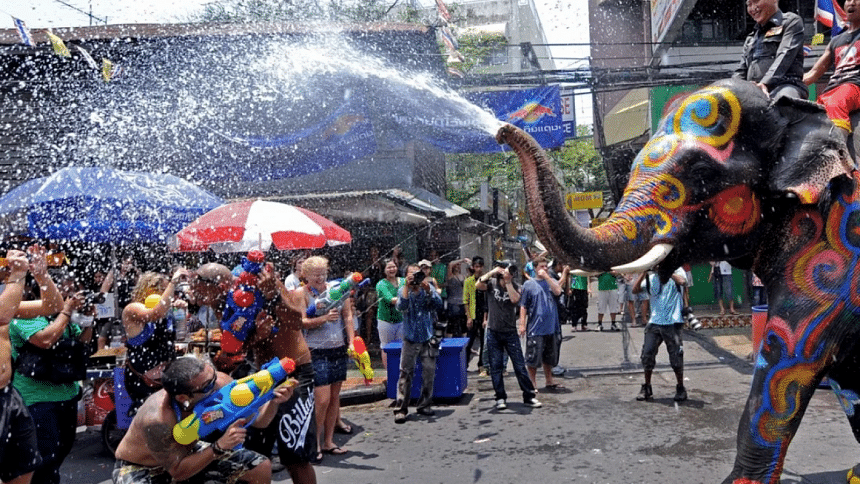

In Southeast Asia, mid-April is a season new years and water festivals. Thailand celebrates Songkran whereas in Laos it is called Boun Pi Mai. Myanmar calls it Thingyan and in Cambodia, it is Chol Cham Thmey.

The Songkran festival signifies the start of the Thai new year and is officially observed as a three-day national holiday (April 13-15). The days are Songkran (festive day), Wan Nao (day for paying respects), and Wan Payawan (day for good luck). The highlight of this event is the water splashing frenzy in Khao San Road, Bangkok's top spot for celebration. All in all, at this time around, stepping out on the streets is asking for a drench not just in Thailand but in Myanmar and Laos too.

Unlike its neighbours, Cambodia has its traditional water festival, Bon Om Tuk, taking place in November. These wild water-throwing parties are a great attraction for tourists. If you're ever here, make sure to pack extra towels and bring your best water-gun because no one leaves unscathed.

The Lao celebration is very alike to its Thai counterpart. The days are known as Sangkhan Luang (last day of the old year), Sangkhan Nao (neither part of any year), and Sangkhan Keun Pi Mai (first day of the new year. Locals don their finest silk and engage in baci ceremonies. Once again, there are processions, fairs, rituals, music, and dance. But also, a beauty pageant, Miss New Year (Nang Sangkhan) is held.

No matter where we are from, this time we pass yet another new year bereft of its glory and high spirits. Meanwhile, we can only hope to soon retreat to times when mass celebrations were not considered to be irresolute, sinister and regrettable.

References

1. The Daily Star (April 12, 2016). Boisabi in the air…

2. The Daily Star (April 13, 2019). Biju brings festivity to the hills

3. The Independent (April 13, 2019). Vaisakhi: what is the Sikh festival and how is it celebrated?

4. The Economic Times (April 13, 2018). Baisakhi, Bihu, Vishu, Poila Boishakh, Puthandu: what the new years of India mean.

5. The Hindustan Times (April 14, 2017). Vishu, Puthandu, Poila Boishakh: Here's what makes India's harvest festival special

6. Northwest Asian Weekly (April 21, 2011). Happy New Year (in April)! — A spotlight on Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Cambodia's new year celebrations.

Hiya loves food that you hate by norm – broccoli, pineapple pizza and Bounty bars. Find her at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments