A Walk to Victory

Trigger warning: Contains references to sexual violence, murder.

Leading up to Victory Day 2021, the SHOUT team recently visited the Liberation War Museum, Dhaka. As young individuals who have grown up only listening to the stories of 1971, it's an ongoing struggle to properly register the horrors of the war, to internally perceive the struggles that led up to it.

The idea was to put ourselves face to face with history, to look at the bloody and bruised artefacts of '71, to learn the stories of individuals, families, and communities destroyed over the course of those nine months. We wanted to achieve a state of mind where the significance of taking victory from the clutches of terrible doom dawns on us in a manner that's as close to the real thing as possible.

The Liberation War Museum takes visitors on a journey through the history of Bangladesh leading up to the war of 1971. Starting from prehistory to the first kings of this region, then onto the Pala and Sena empires followed by the Islamic conquest of the Turks and the Mughals, the exhibit gave us all the necessary background on our history before the British period rolled in and we started seeing the names and faces important to the story of our independence. 1947 came with the promise of a modern nation and the grumblings over a dysfunctional partition at the same time. Our country, known as the province of East Pakistan back then, was slowly reaching fever pitch with revolutionary fervour.

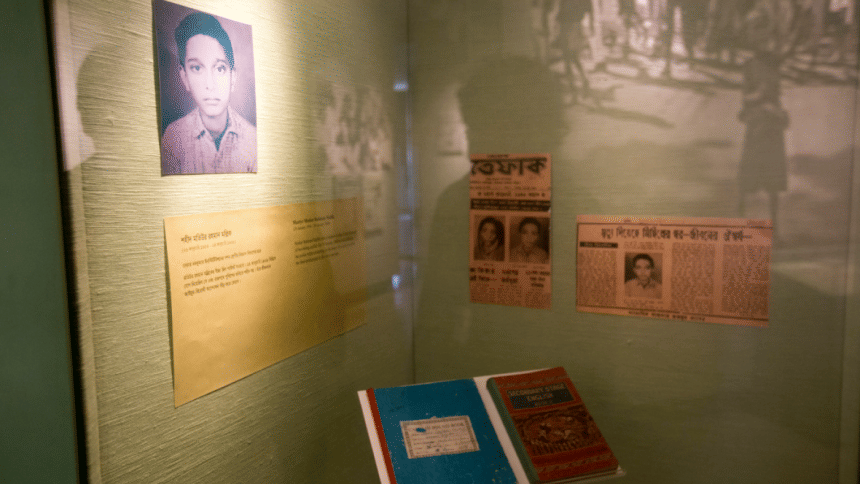

The first exhibit that made us stop in our tracks was the textbook and school notebook of Shaheed Motiur Rahman Mallik. In early 1969, he was a student of Class X in Nabakumar Institution, Dhaka, when he took to the streets and participated in protests that later came to be known as the 1969 Mass Uprising. He was killed by the police on January 24, two days before his 16th birthday.

While his death provided the final momentum to the uprising, this 15-year-old's Secondary Stage English textbook and General Algebra notebook bear testimony to the fact that even the most innocent souls felt passionately about the injustice that Bengalis were subjected to at that time. Motiur Rahman Mallik would have been 67 today, he would have hopefully been enjoying a pleasant retirement after a life full of ups and downs and love and pain. He chose to fight for his future, and that fight took away his life, paving the way for the war that followed and the independence that we were born into.

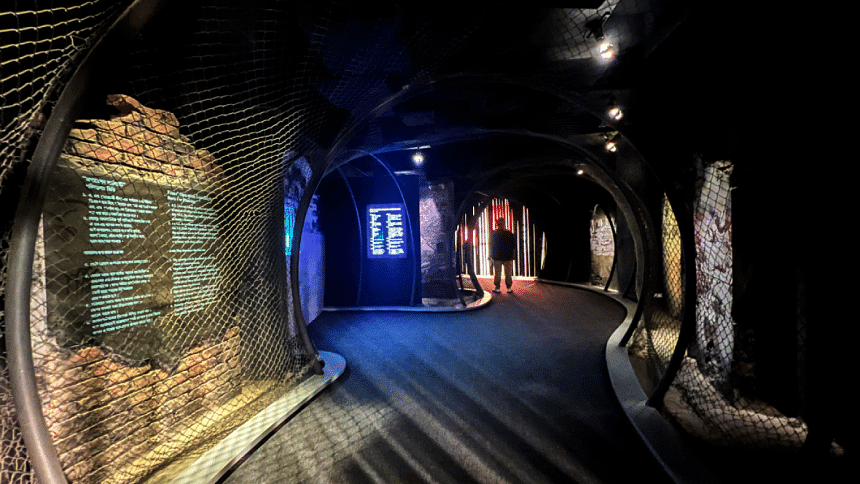

But more had to be sacrificed. Much, much more. As we walked into the next section of the museum, the atmosphere was heavy with dreadful anticipation. A dark tunnel awaited, and upon entering it, we were faced with the terrifying figure of an army jeep, headlights glaring. The enormity of the olive green vehicle imposed itself in that cramped space, and for a moment, the terror of March 25, 1971 was palpable. We could get a sense of what it must have felt like to stand in one of Dhaka's winding alleyways, cowering as one witnessed the onslaught of marauding invaders. What must have gone through the minds of those realising that this procession of olive green monsters was heading towards the part of the city where their families lived?

The ambience was further darkened by the sounds of some of the earliest news broadcasts of what was happening in East Pakistan on that night. Chilling radio communications between units of the Pakistani army were transcribed onto the walls, and helpless anger seethed inside when we read the words they used to instruct each other on how to carry out the massacre, and then congratulate themselves on a "job well done".

The tunnel felt like it lasted for days, and once we walked out of there, we came across the pages of the diary of a young girl, Swati Chowdhury. It immediately reminded us of the Diary of Anne Frank, and how far from reality reading it had felt. The pages were filled with fear that no one, let alone a seventh grader, should ever have to deal with. But she had been there, along with many other children who never deserved any of it.

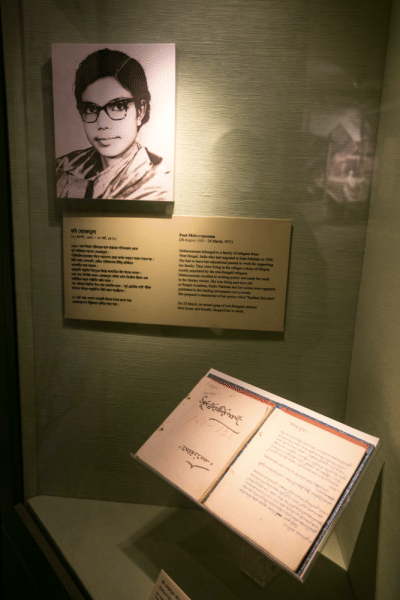

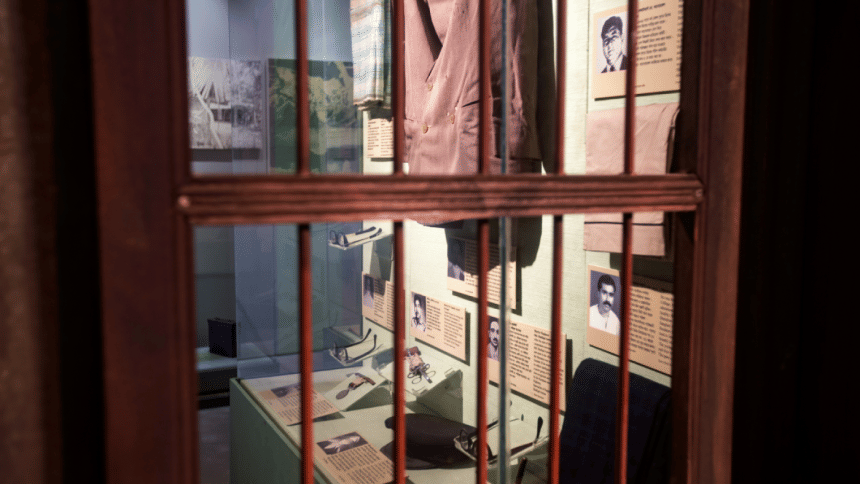

Moving forward, we walked into a dimly lit alley that, at first glance, seemed to have identical showcases mirroring each side with each step we took. A few steps in, we realised that each of these showcases contain memorabilia from the intellectuals murdered on "kalo raat". We had all studied the beginning of the Operation Searchlight through our textbooks and had heard numerous stories, however, that alley had somehow managed to capture the darkness and sense of loss that the words never did.

Out of all the shirts, cane and glasses we got to witness as we walked through the exhibits, the one we all had to stop for was another diary, belonging to the late Poet Meherunnesa. The diary lay open and it felt almost too personal to read. And we were right, the words to her poem Ononno Mukh were too personal. They delivered the essence of losing someone we love, strung together beautifully, and it struck a chord. So we looked up, eager to know this person and her life, and suddenly remembered where we were, and how she, along with all these people, lost their lives too soon. We walked further, holding on to her words, and contemplating her loss.

Independence wasn't achieved through losses alone. We fought back, and the next section of the museum spoke of the history of the armed struggle to drive back our enemies and reclaim our motherland. There were pictures, extended from the ceiling to the floor, of the Mukti Bahini with their guns, lying in wait for the enemy soldiers behind trees and inside tiny huts. There was an exhibit dedicated to the guerrilla warfare that was staged in order to cripple enemy defences, and create panic amongst them.

Guerrillas had very specific objectives. They would move fast and deal with small-scale operations, often behind enemy lines. Many of us already knew about the guerrillas and their contribution in our liberation war. At the exhibit, we got to take a peek at the lifestyle they led during their time as members of the liberation army.

The pictures on the walls set the scene for our introduction into the lives of the guerrillas. The entry was made to mimic the appearance of an actual tin-shed house. From the inside, when you peek out the windows, you get a feel of what it might have felt like for the guerrilla troops to lie in wait as enemy convoys approached their hideouts.

Going past the tin walls, we came across a set of ordinary clothes. These plain clothes, consisting of a shirt and a pair of pants, made up the guerrilla attire. No special uniform, no protective gear. Yet, they would spend hours after hours hiding in remote locations, waiting to pounce on enemy soldiers whenever they were in sight.

Then came a display of the tin plates and pots that these guerrillas used. Within the context of their nomadic lifestyle, these utensils were all the luxury they could ask for. We caught a glimpse of the rules the guerrillas had to follow at all times, written on pages that were taped to a wall near the exit. Trust, discipline, and stealth – these were the key takeaways from those notes. A guerrilla needed to live by that code if they were to carry out their missions successfully.

Perhaps what that moved us the most was the fact that these soldiers were all ready to risk their lives for a cause, not for any honour or reward. They were never promised anything materialistic, nor were they given everything you would expect a soldier to have. Hope was the only thing they needed to fuel their courage and move forward.

However, even hope was too much to ask for the women who were violated, tortured, and held captive for months, in numbers that are too high to comprehend. The room we had now entered was dark, suffocating, and secluded, a fitting acknowledgement of the pain felt by the Birangonas. Greeted by harrowing photos of faceless women, and Quamrul Hassan's painting, The Three Daughters, we were beginning to realise what we were coming face to face with.

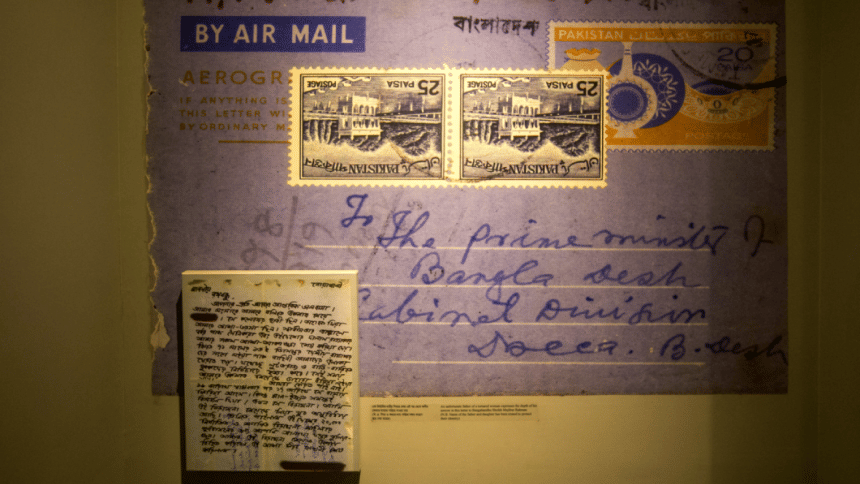

We stood motionless for a long time in front of a series of newspaper clippings and letters. With our hearts heavy and stomachs unsettled, we took in the gravity of each word, filled with plea and desperation, and let the words carve out new wounds. News articles from the time understood the scope of the tragedy, they pleaded to the sensibilities of the world and its citizenry to do something, anything, yet no one answered the prayers. Adding to the helplessness echoed by these old news clippings was the knowledge that even after independence, our state, our people, and our society did wrong by the Birangonas, often rejecting and disowning them, and the tragedy went on.

A corner of the room depicted the vile drawings made on the walls of torture rooms by the heinous soldiers who took it upon themselves to add to all the crimes they'd committed already. We finally exited the room, and the imitation of hell it created, walking by pictures of girls who went missing during those nine months, some never to be found again. The centre of the room remained empty, other than a sculpture by Ferdousi Priyabhashini, a Birangona herself.

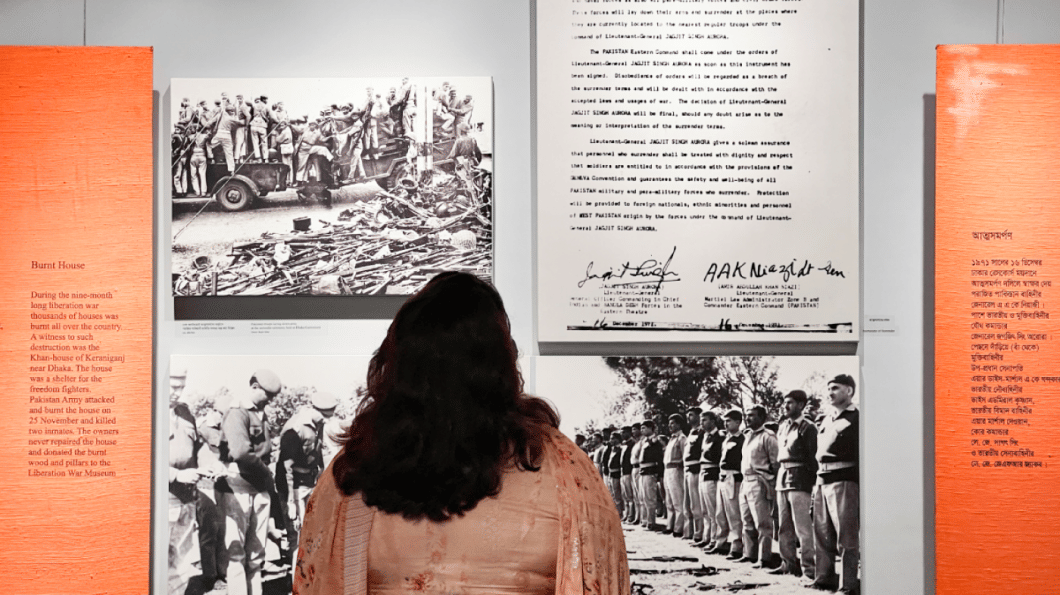

In the span of a couple hours, we had walked through history, and reached yet another beginning. High on emotions, teary-eyed and speechless – we reached the final exhibit, the sweetest moment in the history of this land. The unforgettable, the incomparable December 16, 1971.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that this section was lit up the most, that visitors spent a longer time sitting on the hexagonal bench, taking in the sights and sounds. We smiled as we walked in here, a sense of pride and positivity washing over us, after witnessing the cruelty and barbarism that crippled the nation's intellectuals. We paid our respects to the seven Bir Sreshtho, and from the opposite wall, took in the scenes of the auspicious moment of victory. A screen played video clips of Mukti Bahini soldiers driving through the capital, arms held high, chanting "Joy Bangla!"; photos showed the Pakistani army laying down their arms, defeated. Our walk to victory in the Liberation War Museum culminated here, in the space that contained the proof of the birth of a nation.

The centrepiece, however, was a copy of the Pakistani Instrument of Surrender. The signatures on this document ended the war and created an independent country. The reign of terror drew its curtain with the sunset on Race Course Maidan, illustrated by a similar orange hue in the museum. Bangladesh ushered in a new dawn for her people, and here ended our walk to victory.

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the Board of Trustees and the staff at the Liberation War Museum for their support and cooperation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments