A Conversation with Saikat Majumdar

I think I feel more comfortable imagining women in positions of power than imagining men there. It might be a kind of a wish-fulfilment – I think academia, like many other professional spheres, need many more women in positions of leadership. The structure of abuse revealed by the academic #MeToo movement points to this need.

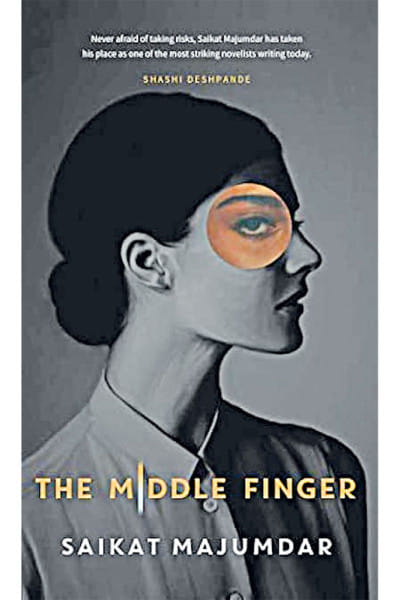

A powerful voice in contemporary Indian writing, Saikat Majumdar delves into the socio- political complexities of modern-day India and often questions the long-standing traditions and rituals. In this exclusive interview with The Daily Star, the Ashoka University professor shares his thoughts on his most recent novel The Middle Finger (Simon & Schuster, Feb 2022).

DS. To some readers the title of your most recent novel The Middle Finger may sound controversial. But as I discovered while reading, it focuses on something very different. Why did you choose this title?

SM. I was drawn to the idea of retelling the Drona-Ekalavya myth in a contemporary university campus. The title comes from a medieval Jain retelling of that story recounted by Wendy Doniger in The Hindus. In this version, it is Arjun who cheats Ekalavya of his thumb. Drona becomes angry with Arjun upon discovering this, and offers the blessing that a Bhil warrior will be able to shoot arrows without his thumb, using his index and middle finger. The last phrase, indicative of unexpected, disruptive strength, became the title of the novel.

DS. On a previous occasion, you mentioned that this book explores the "limits of the teacher-student relationship in terms of ethics, power, and intimacy." But in a teacher-student relationship, the former wields tremendous power and authority over the other. Is there really scope for intimacy here?

SM. A crucial question! Successful teaching or mentoring is the formation of an intimate relationship, perhaps more so with artistic education. Art forges an erotic connection. The professional relation that comes out of it is always an intensely personal one. Here, emotional intimacy is both life-giving and dangerous. To make it sexual or romantic is destructive, since the teacher and the student are in an uneven power relation. But deeply personalized forms of teacher-student relationship figure in the Indian Gurukul tradition, both in myth and reality – and in the gharana/parampara tradition of performing arts in South Asia. But not everything that sounds attractive in art, myth, or imagination, is desirable in reality.

DS. Education plays a key role in The Middle Finger. In all your earlier novels, especially The Firebird and The Scent of God as well, teaching and learning seem to be significant themes. Is there any particular reason behind this choice?

SM. The theme of education lingers over everything I write – fiction, nonfiction, criticism. While I have an institutionalized life as an educator, I feel a hidden part of me feels education to be a process of control that yokes human beings to the dominant order. I guess my writing life seeks to treat education in all its paradoxes, its beauty, its possibilities, but also its deeply repressive function. I imagined The Middle Finger, with a poet and teacher as the protagonist, as caught right in the middle of this – the great power of learning to liberate and motivate people, but also as something commodified, branded and made unevenly available across society. Who gets access to knowledge? Who gets to stake a claim to the teacher? So much of it depends on who you are, and where you come from. Emphatically so in capitalist societies such as the US, but also very much so within the more socialist higher education landscape of the subcontinent, where the inequities of religion, caste and class, I would say, are far more violent and deeply entrenched than the racial divisions in the US. Artistic education is even more complicated as who knows how to draw the line between talent and learning, identity and language, schooling and de-schooling. So yes, one can only think of education as something whose greatest strengths are impossibly entangled with its most terrifying problems. For me, it is an eternally fascinating subject.

DS. I found Megha, the protagonist of The Middle Finger, to be a fascinating and engaging character. As a South Asian woman and academic, I could definitely relate to her. At the same time, I could not help wondering why you chose a female protagonist?

SM. I think I feel more comfortable imagining women in positions of power than imagining men there. It might be a kind of a wish-fulfilment – I think academia, like many other professional spheres, need many more women in positions of leadership. The structure of abuse revealed by the academic #MeToo movement points to this need. While I wanted to create a Drona figure in a contemporary college campus, I wanted her to be a woman. Also, I did not realize it at the time of writing, but I unconsciously created the reality of two women getting entangled in quotidian domestic labor, setting up a home that was a men-free zone. The idea of intimate female friendship without any male presence anywhere draws me powerfully – I think there is much to admire in these friendships. Female characters have always played key roles in my fiction, but this was my first time writing with a female protagonist.

DS. Critics have often called your language lyrical and evocative. Thematically, however, you portray conflicts arising from the clash of different cultures, classes, and education levels. What makes you pull at two opposite strings?

SM. Conflict is lyrical too, isn't it? Conflict lies at the root of art – be it conflict in plot, character, language, emotion, anything. An ethical conflict lies at the soul of Megha's poetry – does she have the right to articulate a certain kind of pain? Does one have to experience certain kinds of suffering directly to own the right of their representation? Teaching, learning, mentorship, everything is ridden with conflicts. Who gets access to the teacher, to elite knowledge? And we know intimacy is the most riddled with conflicts – our greatest conflicts are with our intimate ones. That being said, of all my novels, The Middle Finger is the most divided between cultures, locations, ethnicity, class, sexuality – my previous novels were more uniformly rooted in single cultures. But that is the nature of this protagonist – she is more of a migrant and a traveler, more free and rootless, as it were.

DS. Just out of curiosity: how do you name your characters? Do you think of the story first, or the characters first?

SM. Often my characters have names that mean something relevant to their role and nature – especially characters from the subcontinent. With this novel, I wanted names that sound ordinary, and yet not entirely forgettable. I try to avoid excessively unusual or striking names. I definitely think of characters first, usually characters rooted in a particular place/atmosphere, a conflict in/around them, a character with an innate and interesting tension. What the characters do, where life takes them – which often spins beyond authorial control – becomes the story. I don't really care much about the story, it's the lives of the characters that matters the most. However, this novel was a little different as the myth gave me a path to follow – some of which I ended up ignoring in favor of the demands of local and contemporary reality.

Q. 7. Of all the books you have written, do you have a favourite? If someone asks you to select one of your books as suggested reading, which one would you choose and why?

I think I found my fictional voice with The Firebird/Play House, and that novel draws on some deeply personal elements of my own life, so that's a particular favorite. But The Middle Finger also draws together my abiding concerns as a writer, teacher, student, migrant, and asks questions about creativity and mentorship that are very close to me, so I'm keen to see how readers respond to it.

Sohana Manzoor teaches English at ULAB. She is also the Literary Editor of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments