FEMALE WARRIORS

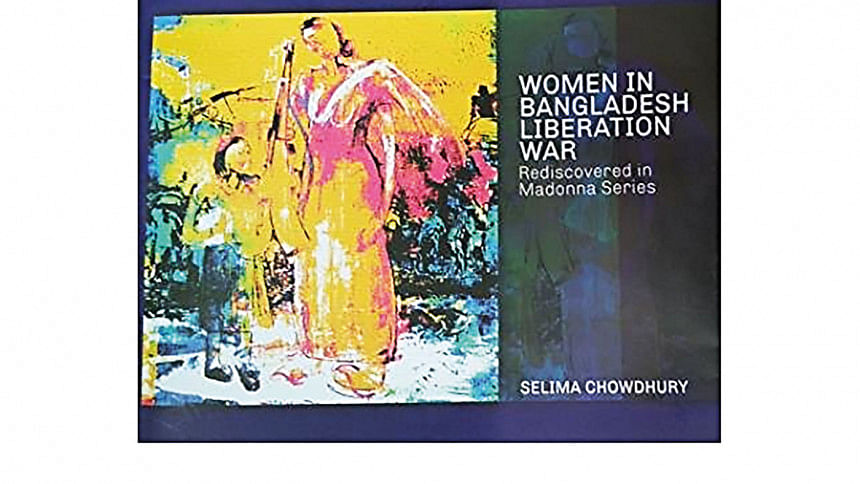

I had decided to write a brief review of Selima Chowdhury's book when it was first published, but what with one thing or another making me put it off, a couple of years rolled by, and we found ourselves caught up in a pandemic with no end in sight. Perhaps it's just as well, for I can now review it alongside a recently published Bangla translation by Ashfaq Khan. The appearance of these two books is cause for celebration, for it is rare for a critical work in one language to be translated into the other. In fact, sadly, it is only rarely that we come across critical studies of our art. One hopes Selima's endeavor will inspire others to take up the pen.

Chowdhury's study is sharply focused on a particular body of paintings by a well-known woman artist of the country, but she does a good job of contextualizing it by sketching in the historical background, the author's biography, the Bangladeshi art world, and in particular the portrayal of the independence war of 1971 in paintings, graphic art and sculpture. Comparative comments serve to enhance our understanding of Rokeya's achievement, and also add to our knowledge of Bangladeshi art in general.

The key to Selima's critical approach is Feminism, which through its varied ramifications has made us more sensitive to the uncritically held assumptions that often skew our view of life and art. Characterizing the country as feminine (it is after all the motherland) leads to an identification of womanhood and nationhood; and, following male stereotyping, womanhood is characterized as weak, vulnerable, and in need of protection, which of course is the responsibility of men. From this follows the plethora of images of youths bearing arms to liberate the motherland from the diabolical occupation forces that sexually assault women. This stereotypical pattern, as a student of mine recently explained in a Masters dissertation (Nasreen Tamanna, The Depiction of Women in the Bangladesh Liberation War: A Comparative Study of War Based Films and Novels, ULAB), is pervasive in our cinema as well. Portraying women as victims only renders them passive, deprives them of agency, and perniciously perpetuates patriarchal values.

Selima "deconstructs" (in a broad sense, not a strictly Derridean sense) these stereotypes by pointing out the insensitive and inhumane attitude to the victims, the "Birangona," by their self-proclaimed protectors, and the "feminization" of the latter when they themselves are the victims of the enemy. She goes on to highlight the pictorial strategies whereby Rokeya avoids falling into these stereotypical modes. Rokeya is inspired by the ideal of empowering women, and depicts them as active agents. The mainspring of her imagination is her experience of being with her protective mother during the terrible days of the independence war. Her mother figures, on the one hand, are related to the Madonna of European art, and non the other, she is a woman warrior who will fight for her child, who is a Christ-like figure. Rokeya depicts women as vibrant personalities playing the crucial roles of helper and care giver to fighters.

Selima concludes: "Rokeya has empowered the women and has attempted to challenge the patriarchal society of Bangladesh by depicting the sufferings and contributions of women during Muktijuddho in the light of feminism." If one has to point out something significant that one misses in Selima's analysis, it is an examination of the technical aspects of painting and graphics. That is to say, the analysis is primarily thematic. An account of the technical dimension would have given us a more rounded view of the subject, for art is not made of ideas but emerges from a sensitive handling of the chosen medium; it is the finesse of the technique that evokes ideas. But Selima has made a good beginning, and one hopes she will attempt a study on a larger scale in future.

Kaiser Haq, a poet, essayist and translator, is currently professor of English at ULAB.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments