Pills, water, trees, and blood

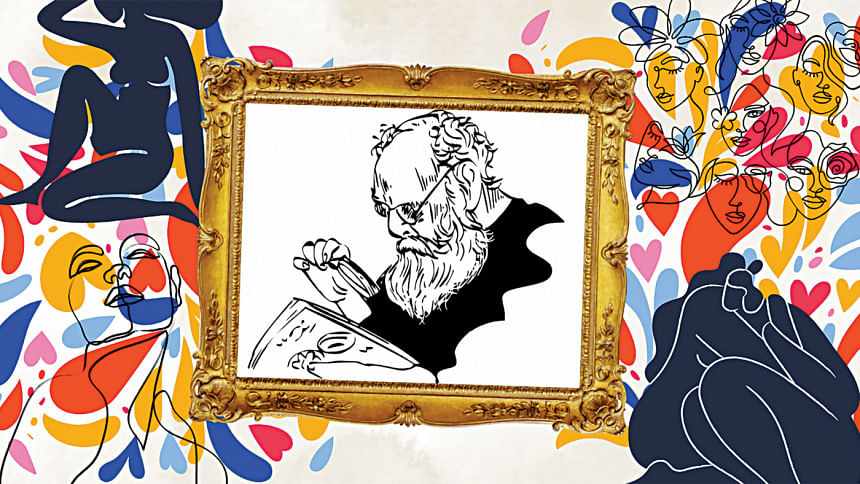

Nuri had just swallowed a little orange pill dry, when she noticed that the portrait of 'The Sexual Revolutionary' had been taken down from the wall of her childhood bedroom. The Revolutionary had hung there since she was a child. Her mom would tell her stories of his escapades before bed, brimming with pride, about his time at the helm of his civil service and his heroic, principled fall from grace. Without him, the room seemed empty.

Then the shouting started. Nuri traced the sound back to the living room. There, Safu, Nuri's older sister, who was usually the last person to lose her temper, was gesticulating wildly, her golden bangles rattling, her voice crackling like thunder. Her dad was turned away from the drama, hunched over his work table in the corner. And her mother, Afifa, was standing, resolute, by the kitchen door, holding in her arms the picture of The Revolutionary.

The family had spent most of the morning cleaning the apartment, trying their best to present an image of 'middle class respectability' as Nuri's father had put it. It wasn't enough. The wallpaper was still peeling, the adhesive completely dried out, and the plastic sofa covers were still ripped and bunched up at the corners.

"Amma, please don't show them that," Safu begged.

But Afifa was unmoved by Safu's histrionics and refused to put down the photo.

"Please," Safu pleaded, two freshly hennaed hands outstretched. "Give it to me. You're going to scare them away."

"What are you so worked up about? They'll be impressed. Your great grandfather was a very important man."

Nuri didn't understand why Safu was so upset. The Sexual Revolutionary had been outspoken in life, some 150 years ago, circa 1925, regularly interrupting dinner parties by discussing the importance of female pleasure. But, he had become much more reserved now that he was confined to the borders of a picture frame, and posed no threat to the discussions of Safu's upcoming nuptials.

"It's not appropriate," interjected Nuri's father. He had been tinkering with one of his favorite analog clocks, trying to right the mechanism that operated its minute hand, when this talk of The Revolutionary had started. To him, The Revolutionary was no hero, but a rotten branch on his wife's otherwise pristine family tree; a branch that he hoped would soon be overshadowed by the addition of Maniv Bilal and the golden leaves, fair skin, clear blood, and fresh waters of his family.

"What do you know? 'Appropriate.' Maniv's parents are worldly. They go to Moscow, Shanghai, Paris. I've seen the pictures. They're modern Muslims, like we should be. Tell them Nuri!"

Nuri had been busy trying to make herself invisible. She was convinced this was the only way she would make it through the day, and was crushed to discover that her efforts had been in vain.

Discreetly, she swallowed another orange pill.

"What did you say? Something about Paris?" Nuri asked, winching her voice up like water from a well.

"What are you doing over in that corner anyway?" said Nuri's father.

"Trying to disappear…" she mumbled back.

"Shona, where are the samosas?" her mother asked.

"Oh," Nuri said with a rueful glance towards the kitchen door. If it was going to rain, as Imran had predicted, she hoped it would start now. Maybe then her family would be so distracted that they wouldn't notice the complete and utter absence of fried goods.

But the Bilals would notice.

As most people struggled to afford the cheapest synthetic foods, the Bilals' inner circle ate lavish four-course meals, and dined with Sheikh Wazed and his cronies in grand halls, under chandelier light—glass and gold.

"Nuri?" prompted her father, his voice sliding into that ominous, rasping register Nuri had spent most of her childhood fearing. He had worked over time at the plant for three weeks so that he could buy the oil, ghee, and fresh vegetables needed for the recipe. After the marriage, he'd never have to work again.

"The filling is done," Nuri offered, rather feebly.

"Oh good. The filling is done." said her mother. "We can feed them mushy potatoes and green peas. That'll give them a rosy picture, won't it? Of what Maniv can expect to eat for the rest of his life."

"I won't be the one cooking for him…" Nuri muttered. In truth, she still hoped that Safu wouldn't be cooking for him either.

"Amma, don't worry, I can make them," Safu offered—always ready to give.

Pretending to cough, Nuri took a third pill.

"Nuri, that's not the point," lectured her father. "And Safu, you can't be handling food. Your henna has barely dried."

"I'll go finish them now," said Nuri.

"It's too late. They'll be here any second," her mother said, her knuckles turning white as she clenched The Revolutionary's frame ever tighter.

"What are we going to feed them? We have to give them something," asked her father, who looked not at his wife or his daughters, but at his beloved wall of clocks—the analogs and cuckoos, the quartzes and atomics, and the hourglass that flipped itself around on the hour every hour.

There was something a little self-flagellating about her father's obsession with time. It didn't matter if he was waiting for his food at a restaurant or using the bathroom, he was always counting the minutes and seconds, and said that since he was a child, as young as four years old, he had felt like his time on earth was quickly draining away, 'like water from a bucket.' The fact that he had defied his own premonition, living 72 long years, through floods and droughts and viral plagues, his heart still pumping, his clock still ticking, provided little comfort.

"We said 10:15? It's already 10," her father said.

It's quintessential masochism, said The Revolutionary. He enjoys the pain.

In a strange way, Nuri hoped The Revolutionary was right, though she wasn't convinced.

"Are you really not going to make the samosas?" her mother asked.

"Oh, I thought you said—" Nuri said.

The Revolutionary stared out at Nuri from the picture frame clutched at her mother's chest.

Go make the samosas, he seemed to be saying with his articulate, bespectacled eyes. Or you'll end up like me—all head and no body.

This is an excerpt from the story "Pills, water, trees, and blood".

Nadim Silverman is a Bangladeshi-Jewish writer and illustrator based in New York City. He studied creative writing at SUNY Stony Brook's MFA program and teaches English literature at Bard Early High School (Bronx).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments