Romancing Wuthering Heights

In popular culture, if not in criticism, Wuthering Heights stands as the tale of love lost in betrayal and a grand reunion in the afterworld. The credit of such interpretation largely goes to the Hollywood movie versions of Emily Brontë's novel, most of which primarily follow the classic 1939 Wuthering Heights with Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon presenting Heathcliff and Catherine as star-crossed lovers, claiming it as the "greatest love-story of our time, or any time." William Wyler, the director, was obviously more interested in making his own version of a great love-story. The title of Wuthering Heights was used to bait the audience and dupe them into believing that they were watching the famous and intriguing story of Heathcliff and Catherine. The movie earned nominations in different categories and won many awards, but it failed miserably to arrest the complexity of the Brontë novel.

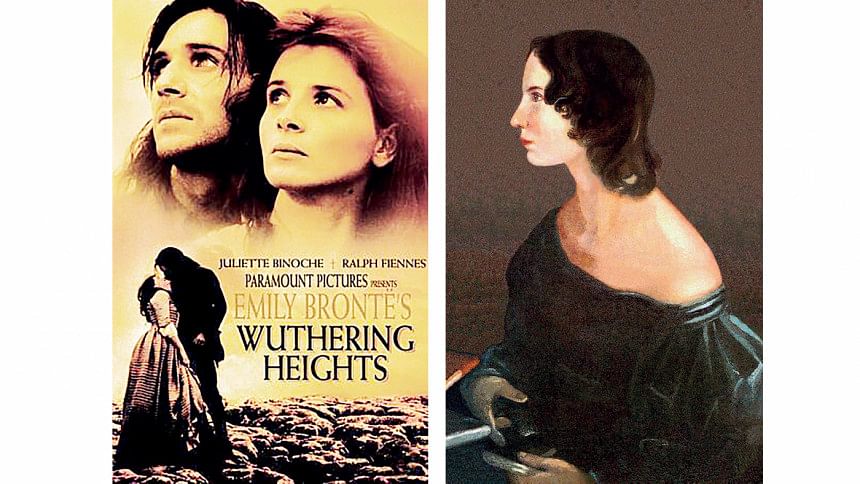

Another classic movie version of the novel is Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights (1992) starring Ralph Fiennes and Juliette Binoche. Even though this is one of those versions in which the characters of second generation appear to play their role of hapless victims, and the story loosely follows the main narrative, this film adaptation is yet another meretricious version of Wuthering Heights. The movie begins with a solitary young woman, presumably the author herself, walking across the moors on a dark and windy day until she reaches a deserted old house, and thinking out loud about the people of bygone times. The obvious idea behind such a beginning is possibly the theory that the house on which Wuthering Heights was modeled is Top Withens, an Elizabethan farm house not far from the Brontës' parish. However, the story that this hooded woman begins is still very different from the novel. There is no other narrator except the lady in blue, and the character of Lockwood is reduced to a luckless middle-aged tenant who stumbles into Heathcliff's household to witness a strange ending of an even stranger story. Moreover, Wuthering Heights, which is also about childhood bonding and adolescent attachment, turns into a movie of triangle love story and reunion of estranged lovers in death—just as it is in most of the other movie versions.

Interestingly enough, most movie versions of Wuthering Heights emphasize Catherine and Heathcliff's union in a life after death, which is never really shown in the book. Both Nelly and Lockwood allude to these "ghost-sightings" by the old servant Joseph, and some shepherd boy and these intimations add a deep and rich pathos to the story. Even though Nelly claims that they are "idle tales," her avoiding of a straightforward answer and Heathcliff's mysterious death suggest that there might be more to the eye than her dismissal and the bland inference drawn by Lockwood. The display of the romanticized ghosts in the movies is perhaps more conclusive but it strips off that poignancy crafted by the author.

The long and short of the matter is that Wuthering Heights as it is romanticized and idolized by most audiences today is not the Wuthering Heights of Emily Brontë—not even the 2011 movie version, which critics find closest to the dreary ambience of the novel. Heathcliff being black brings in racial tension; such adaptations, however, can also make one wonder why all these movies need to focus so much on ghosts, or incorporate foreign elements and delete the childhood of Catherine and Heathcliff.

Some might wince, but in more recent times, the name of Wuthering Heights has been idolized by some young readers for its connection to Stephanie Meyer's Twilight series as the two protagonists discuss the undying love of Catherine and Heathcliff. The novel surely involves a great love story as a central plot; but to summarize it as disgruntled romance and adulterous affair, or a story of revenge, would be overly simplifying of a complex portrayal of life.

David Cecil recognizes in Emily Brontë an aptitude totally different from that of her contemporaries: "She stands outside the main current of nineteenth-century fiction as markedly as Blake stands outside the main current of eighteenth-century poetry." Another critic, Hillis Miller named Wuthering Heights as one of those texts that cannot be read with the assumption that there is only a single truth to be found.

In some strange ways, Brontë touches on the themes and styles celebrated in the first decades of the twentieth century even though she lived and wrote half a century before any of the modernists. The ending, the theme and narrative structure of Wuthering Heights attempt to explain some of the fundamental complexities of life. The fifteen-year-old girl who recognizes the truth about her bond with Heathcliff in spite of the pressures of society that make her choose otherwise; the man who realizes the futility of his revenge mission; the pain and devastations caused and suffered by each of the characters are complex and inconclusive. Along with the rugged beauty and the wuthering of the wind in Yorkshire moors project a strangely intricate world where not all riddles can be solved.

What is this novel about then? Is it about the class differences leading to a romantic betrayal that Catherine laments during her last days? But shouldn't be the seven months pregnant Catherine be more worried over the child she carries than a lover she is leaving behind? However, we never hear her utter one word of concern over her unborn child. On the contrary, she condemns Heathcliff for caring more for his offspring yet to be born. Some might say that the eighteenth or nineteenth-century British women writers were prudish and hence did not discuss pregnancy. But Wuthering Heights certainly is not a novel written by an uptight miss. Her Catherine is a farm girl used to seeing the cattle breeding. Moreover, when Heathcliff accuses Catherine of betrayal, he does it in words that suggest that she has given up something elemental and eternal for a passing whim: ". . . misery, and degradation, and death, and nothing that God or Satan could inflict would have parted us, you, of your own will, did it." Her action is so terrifying and vehement that it destroys the hopes of a peaceful life both for her and those around her.

Even the future generation is drawn into the vehemence of this betrayal. Accordingly, the difference of classes is not so much of an issue here as is Catherine's disloyalty to something more important, perhaps one's own self. Heathcliff's accumulation of wealth is not so much for crossing over to a better class, as Nelly confides to Lockwood that he does so for money. Throughout the novel there is no substantial evidence that Heathcliff cares for monetary benefit in itself. Even after he gains possession of Thrushcross Grange, he chooses to dwell at Wuthering Heights because that was his home with Catherine. Significantly, Lockwood encounters Catherine's ghost at the Heights, and not at Thrushcross Grange where she had died. Brontë's tale evidently involves issues that are more complex than social or moral engagements, questions that are more concerned with one's very existence. Above all, it indicates a significant shift from the orderly and meaningful world represented in Victorian literature.

Referring to the soulful utterances of Catherine Earnshaw as she confesses her love for Heathcliff to Nelly, Virginia Woolf once said that the love she speaks of is not the love between a man and a woman: "Emily was inspired by some more general conception… She looked out upon a world cleft into gigantic disorder and felt within her the power to unite it in a book." Woolf speaks of a "power" beneath the trivial activities of human beings, a power that lifts them "up into the presence of greatness" (131), and she concludes that Emily Brontë's work conveys that very trait. The "gigantic disorder" actually heralds the advancement of a new kind of writing that would be the benchmark of twentieth-century literature. She is indeed a forerunner of the Modernist writers who would explore the essential differences between men and women: biologically, socially and temperamentally. Also, she shifted away from the typical linear narrative of her time and produced such a riddle of a story that continues to remain elusive.

Sohana Manzoor is Associate Professor, Department of English and Humanities, ULAB. She is also the Literary Editor of the Star Literature page.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments