The General’s Time

She woke up to milky streetlight spilled on the bed, his exposed neck in its creamy glow. The dark dip between the wings of the collar bones a misshapen waking eye. Keeping watch. She shifted the weight off her right shoulder to turn to the other side. The shoulder was pulsing a heart-beat rhythm of pain. Pain unlike the kind he had brought on a million of his people. A million pairs of hands that would swim oceans, leap mountains, brave war-zones, to switch places with her. For access to that throat. She landed softly on her left. It was time for the other shoulder to share the pain.

His eyes opened. She was doing it again. Staring at him. It was short, but still long enough. When she did that when she should be sleeping, his hands twitched, his heart banged the drum of his panicked impulse to retreat. Neither his weapon nor his uniform was available. Not anymore. Folded on her dressing table stool, with the discipline of the barracks from half a century ago, were his simple button-down shirt, pants, and undershorts. He had only his bare hands to defend himself from hers. Only his tired old arthritic knees and ankles, and the throb of an ancient femoral injury from a riding accident when his body could take the abuse, to hobble him out of there. Timing was everything.

"Men are tyrants, Julia," her father used to say. "They don't have to look it, wear it, or say it. They just are." Her father boasted a tyrannical personality without being a tyrant. "I'm too strong for that. Weak men become tyrants. Men who couldn't hold their ground without losing control."

She awoke again, time to get up and out of bed, to find him gone, and his clothes no longer on the dressing table stool, his preferred perch for them no matter how much space she offered in closets and drawers.

"Men are tyrants, Julia," her father used to say. "They don't have to look it, wear it, or say it. They just are." Her father boasted a tyrannical personality without being a tyrant. "I'm too strong for that. Weak men become tyrants. Men who couldn't hold their ground without losing control."

She relieved her bladder while he showered.

"Coffee soon," she said. Her voice felt as weary as it sounded. After washing her hands, as she dried them, she contemplated touching the shower curtain. It would cause a miniscule quake in him, which broke her heart to think about. That such a small movement, and that from such a close and familiar source, a hand he knew, a finger he trusted, could be so destructive.

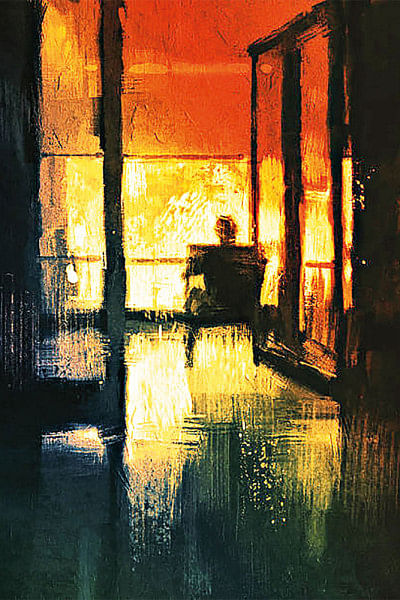

He felt her presence. He had long ago stopped closing his eyes in the shower or while taking a bath no matter how much soap got in and burned them, even with armed guards outside the door. Better men than he had seen their ends with greater odds at being safe. Eyes wide open were a man's true friend.

"Tea for me," he said.

He wanted tea when he missed home. It had to be doused in sweetened condensed milk, too sweet to be tea anymore, almost dessert.

Hassan's tea stall on a misty December morning with the old men huddled around an oil drum fire sipping the best tea on earth. The memory slams him like a mad bull. It hurts.

He could abandon caution to its service. Let them pluck him from the plane and parade him out of the airport to the army stadium – for the spectacle factor – and hang him, shoot him, draw and quarter him, burn his remains in the center of the field. All he would ask for is a cup of Hassan's tea, his last wish.

But Hassan was long gone. He went to his funeral, prayed at his grave, fed beggars outside the cemetery, cried on the ride back to the presidential residence and then into his late wife's arms.

He spooned the condensed milk like it was regular milk, waiting for the gluey, rich liquid to dissolve into his tea, then stirred the mixture until somewhere in his mind he heard the signal that it was ready.

"Maybe," said Julia, "it's safe now?"

He shook his head. She had no concept, no idea, no inkling.

"Omar?" said Julia. "You know people. You have friends. You can get in touch with them in London. You can go and be back without anyone even knowing."

The teacup held to his lips, he took the time to shake his head again before drinking.

"It saddens me to see you like this," said Julia.

He laughed softly, very softly. The kind that made her prickle.

"You're thinking about it," she said. "More every day."

"Do you always act on things you think about?" he said.

"Is that supposed to mean something?"

"It means Do you always act on things you think about?"

"Don't look at me like that," said Julia, placing beats between the words. "I will never be on trial with you. Not you, Omar. Never you."

Twenty-six months existed between his life now and the one that didn't meet a violent end.

"It's over, sir," his chief-of-staff blubbered over the phone.

"I won't ask where you are," General Qureshi said. "I won't even ask why you left without seeing me one more time."

"Sir…" the chief-of-staff sobbed, "my mother is ill. I don't know if I'll see her again."

"Thank you," said General Qureshi.

"Sir," the chief-of-staff couldn't go on. General Qureshi cut the line.

Across from him sat the British and American liaisons. Canada, France, and Germany had coolly crept away leaving their best wishes for General Omar Qureshi's safety and well-being in messages delivered by aides no older than college interns, through third-party intermediaries in their respective foreign offices.

General Qureshi took it as a promising sign that he would live, for the time being. Time enough for the Two Nations to come to his – well, whether he liked it or not - rescue. Imperial masters, past and present, could be counted on to at least consider more ways to lessen the burdens of their guilt.

The American liaison cleared his throat.

"General Qureshi, the US government is ready to offer its assistance for a short-term solution with your safety as a first priority. Sir, you understand our terms."

The terms were for General Qureshi to accept his overthrow and the legitimacy of the interim government. They happened to be identical to the ones set forth by the interim government itself.

London bore a more palatable offer.

"The government of the United Kingdom," said the British liaison, "is ready and willing to offer asylum on humanitarian grounds and in accordance with the Geneva Conventions."

Never failed, General Qureshi thought, like clockwork, never failed how swiftly the condescension followed the generosity. But they were offers and he needed to get out.

"Very well," he said. "May I offer you gentleman tea? Or coffee? Or both?" The two men looked toward the sound behind the General, an intake of breath. The General, waiting for their answer, paid it no mind.

Nadeem Zaman is the author of the novel In the Time of the Others (long listed for the 2019 DSC Prize in South Asian Literature) and the story collection Up in the Main House & Other Stories. His fiction has appeared in journals in the US, Hong Kong, India, and Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments