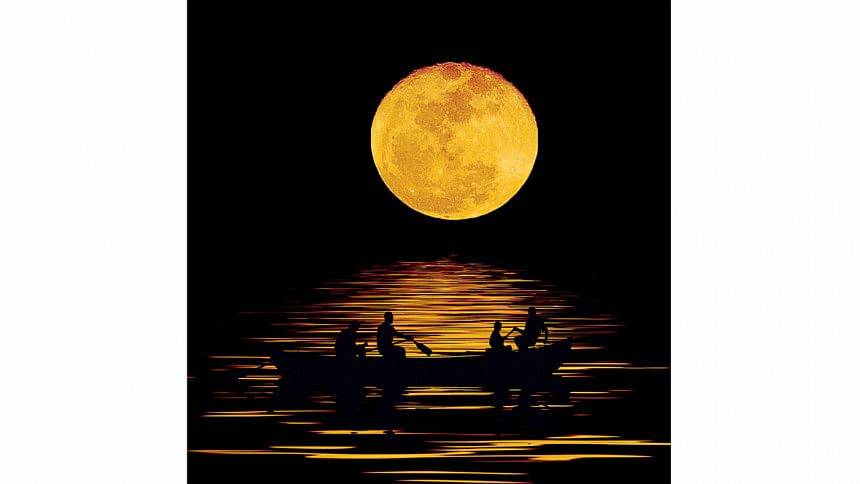

‘Twas Full Moon That Night

The village folk remembered the moon of that night, and they described it. The day after Mafijuddin Miya of Suhasini and his family were murdered by assailants on a cloudless full moon night in the month of Bhadra, some of the villagers gathered in the compound of Mahir Sarkar's house. Even though quite some time had gone by, they could not get over their shock at the suddenness of the incident. They sat speechless amidst the smell of cow dung and straw on the long bench in the outer courtyard of Mahir Sarkar's house and puffed on the flat-bottomed hookah. The sensory deluge that they felt at the watery sound of the hookah being puffed in the soft and cold light of that dawn seemed to make the previous night's incident float like a distant nightmare, and references to the moon in everything seemed to become significant to them. They could remember that a gigantic moon had risen the previous evening. Perhaps there was nothing exceptional in that awakening of the moon; but the incident that took place in the village of Suhasini on that full moon night in the month of Bhadra stunned the villagers; but after that, when they failed to explain and analyse the incident, they speechlessly puffed on the hookah in the courtyard of Mahir Sarkar's house and all that they kept thinking about was the full moon. Then Torap Ali, who was rapt in the hubble-bubble sound of the hookah and the fragrance of the special tobacco infused with herbs, spoke; he said that last evening, he was bringing home the calf that had been tethered at the edge of the road; he elaborated, At first I didn't understand, I had a strange sensation in my body, as if I was in a trance-like stupor, there seemed to be dust all around, but the dust had a strange quality, it seemed to be suffused with a hue; I didn't know what it was, I just knew it must be something; after that when I arrived in front of Miya's house, I understood what it actually was; Dehi ki myabarir mathabhanga aamgastar dain paash diyya punnimar chan bhaisa uttse, I saw that the full moon was floating up on the right side of the headless mango tree in Miya's house. All the villagers remembered that moon, and as they sat in Mahir Sarkar's courtyard, they said that it had occurred to them that a bloody moon like a decapitated head was rolling over the village. The village folk could not understand why the assailants preferred the luminous full moon night over the darkness of the new moon; they only kept wondering about, and being astonished by, how Mafijuddin Miya could possibly be dead; after all something like this was not supposed to happen, he was supposed to live till he was 111, and they had learnt that he was only 81. While speaking in Mahir Sarkar's courtyard, Torap Ali,, too got awfully confused about the matter; he said, Aage johon ami myashaaber chul kaittyam tokhon myashaab ekdin amak shei chinno dehaisilo. When I used to cut Miya saheb's hair, Miya saheb had one day shown me that sign. Hearing him, the villagers could remember that Torap Ali once used to work as a barber in this village, it was true; later, in the face of constant threats by his wife he changed his profession and opened a small provisions store in the village. Torap Ali said, Long before opening the provisions store, I was cutting Miya saheb's hair in mid-afternoon under the persimmon tree in Miya saheb's house; I wrapped a white sheet over Miya saheb, but his arm, from his elbow downwards, was sticking out of the lower end of the sheet; Torap Ali said that after a while, as he was working the scissors speedily, he noticed that Mafijuddin Miya had spread the upturned palm of his right hand on his thigh; he continued, Chandaikona thaikte ami johon chul kaatar kaam shikhi, tokhon ek ostader kase ami manusher haat dekha shikhchilyam.When I learnt hair-dressing while living in Chandaikona, I also learnt how to read people's hands from a teacher. Hearing that from Torap Ali, even in that exceptional time, the village folk felt kind of confused, they could not recall whether they had ever heard that the former barber of the village knew astrology; but it was not an apposite time for argument, so despite their confusion they merely gazed at the speaker's face silently and listened.

Torap Ali said that at that moment he observed an exceptional palm spread out in front of him; looking at the blank faces of the peasants who had gathered in Mahir Sarkar's courtyard, he explained, My teacher taught me that four things influence a person's life, one of those is the Sun, after that come the Moon, Mars and Saturn; the calculus of the reign of these four entities lies in one's hand; if Saturn reigns supreme then the ship of business suffers, pests infest the crop, owls hoot in the darkness, and bad times arrive; but if it is the Sun that reigns, then one's heart is full of courage and Saturn remains under control; if Mars becomes the king, then all is good; but what happens, Teacher, if the Moon reigns supreme? I asked him that, and my teacher said, There's no good or bad there, or it's both good and bad; when the angels pour the light of the moon on earth, the souls of trees, animals, and birds become still, and the one who enters the kingdom of the moon is unable to say whether he is awake or asleep, it's as if he merely walks along in a stupor; That was what my teacher had told met; and that day, under the shade of the persimmon tree in the courtyard of Miya's house, I observed on the upturned palm of Miya saheb's hand that the reign of the Sun was dominant, but the mound of the Moon on the palm of his hand overpowered that. Torap Ali said that after observing the lines on Mafijuddin Miya's palm on that long-ago afternoon, he had turned terribly restless. Because, said Torap Ali, The lines on a human hand descend from the fingers towards the wrist, but the lines on Mafijuddin Miya's hand were knotted together somewhere near his wrist and from this knot, lines like three strings of twine ran down towards the fingers and fell into the hollow between the little finger and the ring finger, the ring finger and the middle finger, and the middle finger and the index finger. Torap Ali added that on witnessing this sight of the lines on Mafijuddin Miya's palm seemingly dropping down from his fingers, he had an uneasy feeling, and he had felt a strange kind of fear; he said, I stopped cutting his hair and kept gaping, and I asked him, Miya saheb, why are the lines of your hand like this? I couldn't figure out whether that annoyed Miya saheb, but he turned kind of grave, and in turn asked me, Like what? I picked up courage and replied, It's as if it's rolling down, it's like something falling down to the ground. When I said that, Miya Saheb examined his hand, as if he had never seen his own hand before; after that he slung his arm down at his side and said, Je jinish jhoira pore Torap, ta hoityase jebon, ei haat theikya ja jhoira pore ta hoilo tyaj; amar ei bari aar ei gerame ami ki jebon aar tyajer abaad kori nai? It is life that falls off, Torap, and what falls off this hand is vigour; did I not cultivate life and vigour in this household and village? The people of Suhasini who had gathered at Mahir Sarkar's courtyard steadily got entangled in the web-like branches and sub-branches of the tale that Torap Ali unfurled; turning his gaze towards them, and taking a long puff on the hookah, he said that even after hearing what Mafijuddin Miya declared, he felt a strange fear, and observing his fear Mafijuddin Miya had told him that he did not believe in palmistry; he had said, I will live to be a hundred-and-eleven, that has already been fated. Torap Ali said that Mafijuddin Miya undid the knot of his lungi in the dark shade of the persimmon tree that afternoon, revealed his right buttock, and showed it to him, and Torap Ali mentioned that the number '111' seemed to be written with black ink on the skin of his buttock, wrinkled by age; he continued, Somehow the fear did not leave me, but I didn't realise what it was then; now I realise that it had occurred to me that it was blood coursing down the lines of his hand; When I brought the calf home yesterday evening and observed the flaming red visage of the moon, I had it in my mind, but I don't know why I didn't realise it then, that it was this moon that had slipped off and floated out of Miya saheb's hand, the moon was soaked in blood. When Torap Ali stopped speaking, the village folk kept recalling the moon in detail; although they were not convinced of Torap's proficiency in astrology, nevertheless a suspicion arose in the minds of some of them, those who were old now, who had seen Mafijuddin in their childhood and adolescence, or heard about him, that Mafijjudin Miya probably had some kind of bond with the moon.

The people of Suhasini recalled that Mafijjudin's Ma was mute, she was incapable of making even the slightest sound, and the night this mute woman was convulsing in soundless agony atop a bloodied haystack while giving birth to Mafijjudin inside their ramshackle hut on a fallow plot on the bank of a canal, Mafijjudin's father, Akalu, was sitting outside beside the door and savouring a smoke. The people of Suhasini later learned that Akalu's mute wife gave birth to a son after a lot of suffering, and at the very moment of the boy's birth, Akalu, who sat waiting outside beside the door, heard the cries of the infant floating out from inside the room, and after that, a shaft of moonlight flashed through the canopies of the trees and fell flat at his feet. Akalu later told the village folk that as soon as the baby cried out, the moonbeam emerged and fell, dispelling the congealed darkness, and then he realised that it was full moon that night and that this full moon had been in eclipse all this while; the baby was born the moment the eclipse began to lift, or alternatively, the eclipse began to lift the moment the baby was born. Akalu said, Ghorer moidde sawaler chikkhur huinya choimkya uttsi, dekhi ki, amar dain paayer paatar upur chander alo aishya poirse, I was startled to hear my boy cry inside the room, and lo and behold, what do I see, moonlight had fallen on my right foot; he added that his heart filled with joy at once, and after that, entering the room, he found the baby lying on the wet straw between his weary wife's legs, just like the people of Suhasini said he once found this silent wife of his. But, that night he could not pick up the human baby after he entered the room because of his wife's fatigue-induced slumber; he observed that the connecting cord between the newborn baby and his mother was still intact. Seeing the baby in this condition, he then felt like laughing because it struck him that the baby was stuck like a baby goat tethered to a pole; but either without giving it any thought, or owing to a kind of unknown fear, he folded his arms. Instead of trying to set the baby free by pulling the cord out of the uterus, he simply waited. After that, when the baby was separated with the placenta emerging from the uterus, he put the baby next to the bosom of his naked mother who was lying on the straw in the darkness; he came out, and looking up at the sky, he saw the moon gradually emerging from the malefic clutches of Rahu, and moonbeams began to rain down upon the leaves of trees and on the fields, and it seemed to Akalu that he could hear the pitter-patter sound of these falling moonbeams in the night's silent realm. Sitting on the veranda near the door of his hut, he lit the tobacco in his chillum from the fire made with paddy chaff and smoked; after that, when the full moon was completely unveiled and it bloomed directly overhead, he went back inside his hut and he heard the slurping sound of a breast being suckled. Akalu, the landless farmer of Suhasini who lived all alone with his mute wife on a fallow plot of land, then got busy; he cut and brought laths from the clump of bamboo behind the homestead, and removing the baby from his mother's bosom, he carried him to the moonlight outside. He then cut off the umbilical cord of the infant using the bamboo laths, and tied its stump with a thread, and in the radiance of the heavy downpour of moonlight on the homestead through the gaps in the foliage, he washed the baby with water from the pitcher.

This is an excerpt from the Bangla novel, Shei Raate Purnima Chhilo, by Shahidul Zahir, translated by V. Ramaswamy and Shahroza Nahrin.

V. Ramaswamy and Shahroza Nahrin translated Life and Political Reality: Two Novellas by Shahidul Zahir.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments