Ulysses turns 100

In March 2021, having barely sketched the outline of his last two chapters, Joyce learnt heard from Harriet Weaver the refusal of the American publishers to bring out his book. On April 5, 1921, he went to rue Dupuytren and shared his despair with Sylvia Beach. "My book will never come out now," he told her. On an impulse, Sylvia asked him if he would let "Shakespeare and Company" publish Ulysses. A jubilant Joyce gave his immediate consent.

In memory of Maurice Goldring

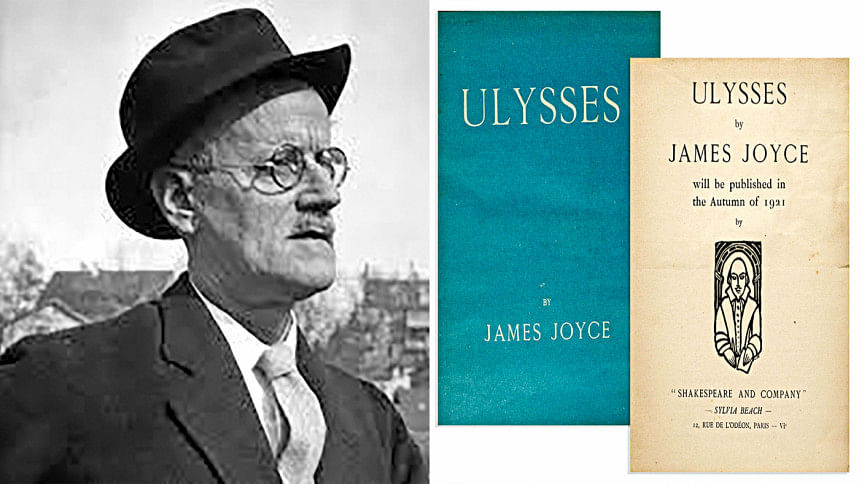

On Thursday, February 2, 1922, a young woman was pacing the platform of the Gare de Lyon while waiting for the express train from Dijon. At 7:00 am precisely, the train arrived, stopped slowly, the conductor got off, looking around for the young woman who rushed to him and took a package from his hands, holding it tight while running towards the boulevard below, where she hailed a cab, her heart pounding. Less than ten minutes later, she reached N° 9, rue de l'Université, tore up the stairs, rang a bell and gave some of the precious contents to the tall, lanky, and partially blind man who had opened the door. With a smile, he took hold of the object and made a gesture of thanks. He was turning forty on that day and this was his birthday present. He was James Joyce, the Irish author everyone was talking about. She was Sylvia Beach, the young American who ran the English lending library "Shakespeare and Company." As for the object, it was one of the first two copies of Ulysses, a masterpiece of literary modernism, which had been eight years in the making and whose publication he owed precisely to Sylvia Beach. Without lingering, Sylvia took leave of James, jumped into a cab, got off at 12, rue de l'Odéon where she hastened to place the second copy in the window of her bookshop.

This was the happy conclusion of a publishing odyssey fraught with twists and turns, unique in its kind, an adventure which probably has no equivalent in literary history, on a par with this extraordinary book that is much talked about (and not always in a good way) but not widely read, his access being deemed too forbidding. Its publication was also an odyssey of sorts. In 1919, the English magazine "The Egoist," edited by Harriet Weaver, had to stop the serial publication after five issues, following protests from printers and subscribers; in 1920, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, the editors of "The Little Review," an avant-garde New York magazine, were condemned by the court for having published "obscene" material and ordered to stop the publication of Ulysses.

Trieste-Zürich-Paris, 1914-1921. Ending on the mention of these three places and two dates related to its writing Ulysses is itself a novel whose "non-action" takes place in yet another place, Dublin, on a single day, June 16, 1904. Modeled on Homer's Odyssey, with an Irish Jew, Leopold Bloom, as the avatar of the Greek Odysseus, Stephen Dedalus as Telemachus, and Molly Bloom as Penelope, this novel is the work of a peregrine, but even more so of an exile, of a wandering Irishman who chose exile to escape the conformism and paralysis of a country under English colonial rule, but above all of a "priest-ridden" society, stifled by the straightjacket of a retrograde Catholicism which, paradoxically, was to be the sole subject of his writings.

A free and feverishly independent spirit, Joyce was nonetheless dependent on a network of admirers dazzled by his literary genius. Prominent among those were Ezra Pound, Harriet Weaver and Sylvia Beach who, each in their own way, facilitated his rise to fame and his claim on posterity.

It was Pound, an American poet and critic living in London from 1908, who persuaded Harriet Weaver to serialize A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in her magazine The Egoist between February 1914 and September 1915, despite the communication difficulties between Trieste and England caused by the ongoing World War. Pound can rightly be considered as Joyce's "discoverer" and his informal literary agent. Pound it was again who convinced Margaret Anderson to resume the publication of Ulysses in The Little Review, which resulted in the trial. Pound and Joyce corresponded for seven years before meeting for real in June 1920 by Lake Garda where Joyce told him about the setbacks in his attempts to get Ulysses published, the magnum opus he had been working on for six years. The following year, the American suggested that he come to Paris for a few months. The cost of living was low, and the French capital was, at the time, "an artist's paradise". The Joyce family arrived in Paris on July 9. The meeting that was decide on the future of Ulysses took place two days later.

Since her return in 1917 from Serbia, where she had worked for the Red Cross, Sylvia Beach had been living with Adrienne Monnier, whose bookstore and lending library, "La Maison des amis du livre", at 7, rue de l'Odéon, served as a model for her "Shakespeare and Company", which she managed to open in November 1919 at 8, rue Dupuytren. On Sunday, July 11, 1920, Adrienne Monnier attended a party given by French poet André Spire. It is there, on the second floor of 34, rue du Bois de Boulogne that Sylvia Beach, who had just accompanied her lover, met the "great James Joyce". The two of them instantly took to each other: Joyce loved the beauty of Sylvia's voice and the way she talked about her activity as a bookseller; Sylvia fell under the spell of the inflections of Joyce's Irish voice and his total lack of affectation, and she was moved by the mixture of strength and fragility that emanated from his long and thin body. The next day, Joyce, his legendary ashplant stick in hand, pushed open the door of "Shakespeare and Company," where he picked up his membership card and confided to Sylvia Beach the difficulties of getting Ulysses published.

He also told her about Harriet Weaver, who had published his Portait in serial form in The Egoist and sent him his royalties along with large sums of money. A left-wing feminist, Harriet Weaver was the heir to a small family fortune that she had decided to spend to the promotion of Joyce's work, very much in keeping with her political ideals.

In March 2021, having barely sketched the outline of his last two chapters, Joyce learnt heard from Harriet Weaver the refusal of the American publishers to bring out his book. On April 5, 1921, he went to rue Dupuytren and shared his despair with Sylvia Beach. "My book will never come out now," he told her. On an impulse, Sylvia asked him if he would let "Shakespeare and Company" publish Ulysses. A jubilant Joyce gave his immediate consent.

Despite no prior publishing or communication experience, Sylvia Beach had taken upon herself the responsibility of publishing a contentious text that was still in progress. Her pluck, strength of conviction and ability to seize the opportunity by the forelock, turned this daughter of a presbyterian minister into the extraordinary promoter of one of the most important books of all time.

A born organizer, she called upon the talents of the Anglo-American community in Paris and set up a formidable communication plan and an effective publication schedule. The first print run of 1,000 copies was entrusted to Maurice Darantière, who was already working with Adrienne Monnier and was based in Dijon. Expenses were to be covered by subscriptions, targeting primarily the Paris expatriate English-speaking community, as well as their wide network of acquaintances. Subscriptions soon began pouring in, mostly from Britain, but also from Europe and the United States. In Britain, the list of subscribers included Winston Churchill, Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, Aldous and Julian Huxley, the Sitwell siblings, H.G. Wells, T.E. Lawrence and Yeats. In the USA, Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams and John Quinn, the lawyer who had represented Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, were among the subscribers. At night, Robert McAlmond, an American poet and short story writer living in Paris, would scour the cabarets in search of subscribers, and in the early hours of the morning drop the forms, some of them filled out in the shaky handwriting of people who would later be surprised to learn that they had committed themselves...

In this extraordinary display of enthusiasm and optimism, three people stick out like as many sore thumbs. George Bernard Shaw, whom Joyce held in low esteem, who refused to pay 150 francs "for a book like that." Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas, two Americans in Paris notorious known for their lack of interaction with the natives, who cancelled their membership of "Shakespeare and Company" as soon as the announcement of the upcoming publication of Ulysses became known.

McAlmond was part of the small army of "Beachians" who worked tirelessly on the publication of the Joyce's great work, along with Sylvia's sister Cyprian, Myrsyne and Hélène Moschos, young polyglot Frenchwomen of Greek origin, and several Cambodian students, including the heir to the throne.

The main concern was to establish the final text. As Joyce wrote by hand, with pencils bought at WH Smith, his texts had to be typed to be sent to Darantiere. Several typists refused to type a text that was sometimes openly bawdy. The husband of one of them, who worked at the British Embassy in Paris, was so disgusted at what he had read that and threw half a dozen pages into the fire. Also, because Joyce kept adding text to text, Robert McAlmond, who was typing the last chapter, "Penelope" took it upon himself to rearrange in his own way some of Molly Bloom's thoughts. Surprisingly enough, Joyce did not object to the result.

In the meantime, on July 27, 1921, "Shakespeare and Company" moved to 12 rue de l'Odéon, virtually opposite Adrienne Monnier's bookshop, the two places becoming one. The literary tout-Paris stopped by on rue de l'Odéon. Fascinated by Joyce, who has become his friend, Valery Larbaud, the translator of Samuel Butler, planned to give a lecture on Ulysses, which made it necessary to translate some of its passages into French. He was assisted in this work by Léon-Paul Fargue, a great poet who had a perfect command of the "bawdy idiom," and by a young music student, Jacques Benoist-Méchin, a close friend of Adrienne Monnier's, whose input was have a major impact on the text and influence future interpretations.

Joyce selected the excerpts to be translated, taken from "The Sirens" and "Penelope." Though he was dazzled by Joyce's genius, Benoist-Méchin (a future collaborationist who had Sylvia Beach released from prison in 1943) pointed out to Joyce that concluding Molly Bloom's monologue with "...yes I will..." sounded somewhat too abrupt and authoritarian. He recommended ending the text with a "Yes" that would be more in keeping with the spirit of the text, the most positive word in any language testifying forcefully to the existence of a world beyond individual consciousness. As with McAlmond, Joyce eventually agreed with the suggestion, which has since illuminated the work in retrospect. It can be tentatively asserted that Ulysses is a collaborative work of sorts...

Held on December 7, 1921, Valery Larbaud's lecture was a huge success. The 250-strong attendance gave Joyce a standing ovation as he appeared from behind a curtain at the end of the event.

Finally, on January 5, 1922, after Joyce had added about 20% new material to the original text, the final proofs were at last ready.

On Friday, January 6, to celebrate the event with dignity, Joyce invited Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier for a celebratory meal at Ferrari's, his favourite Italian restaurant. It was agreed that the publication date would be February 2, Joyce's fortieth birthday, an auspicious date for someone who was deeply superstitious.

The next day, on Saturday, January 7, in Dublin, the Dáil Éireann, the Irish parliament, voted by a majority in favour of the Treaty that put an end to the Anglo-Irish war and established the independence of the Irish Free State, i.e., the island of Ireland minus the six northeastern counties, mostly Protestant, which remained a part the United Kingdom and became the province of Northern Ireland. This double birth can be endlessly discussed – can it be seen as a mere historical coincidence, or is it the result of some necessary synchronicity? In any case, at the very moment his country joined the concert of free nations (and on the eve of a terrible civil war), Joyce was about to brought into the big wide world a novel that was not only to "forge the conscience of his race" but also and above all usher Irish literature in on the modernist scene. Incidentally, it was to give his "fans" the opportunity to celebrate "Bloomsday" every June 16th since 1954 (and the historic, rumbustious, pilgrimage organised by Flann O'Brien and Patrick Kavanagh), dressing up as the characters of the novel and acting out some its scenes while imbibing generous amounts of various liquid substances.

Before this literary earthquake occurred, the crucial and thorny issue of the color of the jacket remained to be settled. Joyce insisted that it should symbolize the Mediterranean Sea and match perfectly with blue of the Greek flag. Eventually, Darantière had to go all the way to Germany to find the right blue, which he had lithographed on white cardboard. Ulysses as an object had finally become a reality.

On the evening of February 2, 1922, the day of his fortieth birthday AND of the publication of his most successful book, James Joyce returned to Ferrari's with family and friends. Glasses were raised in the honour of Joyce and his novel, which he had placed religiously on the table. The evening ended at Café Weber, rue Royale, a little too sedately to Joyce's taste, who would have liked to celebrate all night long.

Yet another battle was about to begin, which Joyce had to fight to have Ulysses published in the United States (in 1933) and in Great Britain (in 1937). In the meantime, the various editions illegally brought in these two countries (sometimes "disguised" as Shakespeare's complete works), were confiscated, burned in public, but also, fortunately, avidly read. Strangely enough, Ulysses was never banned in the Irish Free State, on the grounds that it was never officially sold or smuggled there...

On the centenary of the publication of Ulysses, the author of these lines would like to make a humble request aimed to popularize the reading of Ulysses. In the same way as Anthony Burgess once published a Shorter Finnegans Wake, a selection of key passages linked by various summaries he himself penned, I strongly advocate the publication in French of "selected passages" of Ulysses, which would take after Burgess's work. Ulysses deserves to be rid of its mystical status of closed and sacred text. Now it is in the public domain, it is high time as many people as possible were given the opportunity of tasting the very substance of the text.

May I be forgiven for the somewhat daring shortcut that follows, but it seems to me that in 2022, one hundred years after the publication of Ulysses in Paris, the time for a Joycean #MeToo has come.

Yes

Olivier Litvine, associate professor of English, Joycean activist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments