What He Did

He joined the army at eighteen; a soldier through and through. He was tall, sturdy, ruddy-faced, and almost always urbane. Mahmud was my neighbour for nearly five years. He had moved from barely inhabited hilly terrain of Khagrachhari to the city of a heightened breeding place, old Dhaka. His decision to leave the vacuous and soulless life of the barrack could be being closer to his own children– all of them were assumed to be in their primes.

"I have six," he once told me. "Seven," he corrected himself a second later. Two from each of his three ex-wives and one boy whom he had picked up during an eviction mission in Bangladesh Myanmar border when his platoon was making their way through the fur-flung jungle of Ukhyia when there was a state of emergency in Rakhine state in a series of besmirching battles between Rohingya and Myanmar Army. The village had been raided just a few days before they got there. "There were severed and burnt bodies strewn everywhere," he proclaimed. Some people were still trying to salvage whatever they could. He drifted onto a discarded flotsam when a little girl crawled up, speaking inaudible Arakanese and crying, asking him to take the sickly nine-month-old baby she held in her arms.

He took the baby; fed him some dry food, and a few days later he handed the child over to the mobile Red Cross team. He also registered the baby as his own giving the baby a Bangladeshi moniker "Babu Miah."

I thought of inviting old Mahmud to come and join for an adda fuelling feast. My kids always enjoyed chatting to him; he was sardonically funny yet quite affable with them. However, he was nowhere to be seen.

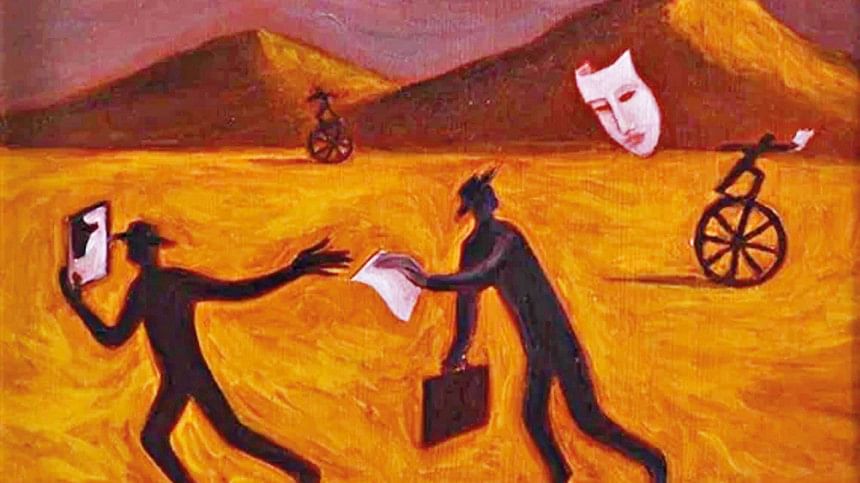

He was a career soldier; he had been in the UN mission to Africa, Middle-eastern Asia, and other missions. But he couldn't reminisce about those memories in a buoyant mood. He had seen the good, the bad, and the ugly side of humanity for the umpteenth times.

Every morning, I would hear him working at his backyard as the music played from his tape recorder, always local folksong. I would usually see him working on household chores, his old tape recorder; tinkling with things, taking them apart, and putting them back together. One evening, he played something from Lalon's mystic melody. A galaxy of memories fizzed through the beam of his conscience and it took him into a state of surreal stupor. The music seemed to pour salt into his unvoiced wounds as he crooned, — "O the woe-fraught bird in the cage… How do you fly repressing all your rage?"

More often than not, he and I would bask in propitious camaraderie on the weekends talking through an opening in the wall that had separated our properties. Once in a while, his old comrades would traipse all the way to Tathari Bazar to come and visit him. But as far as I remember in those five years he had been my neighbour, his kids never came to visit him.

Mahmud would sometimes tell his kaleidoscopic range of stories, often recalling his childhood and his teens. How he signed up to be in the army the day after he passed matriculation simply because he didn't want to go to school anymore.

One sluggish Friday noon, as my family and I came back from Jumma prayer, I had prepared to marinate the beef to cook in the backyard. I thought of inviting old Mahmud to come and join for an adda fuelling feast. My kids always enjoyed chatting to him; he was sardonically funny yet quite affable with them. However, he was nowhere to be seen.

His old bicycle was parked in the front doorway; the bicycle he'd been working on was in the backyard along with the little tape recorder. I could hear music streaming out from the garage. I called out to him but I didn't hear a response.

Knocking on his front door, and upon getting no reply, I surveyed around to the wooden door on the side of his house but it was locked. Tidying up the backyard, and cleaning the temporarily built fireplace, I went back to my house and set about my business.

My wife was inside the house taking a nap and my kids were in the living room playing and watching Friday matinée show on television. As I started to dredge up the makeshift hearth, expecting him to bob up with one of his friends, suddenly I heard a groan. At that moment, I decided to peep through the door hole.

There he was on the floor. He had fallen from a chair under his workbench. I called out his name, but he didn't respond. I tried to pry the door open. Then, I shattered the window in, removing the craggy board and unlocking it from the inside, I rushed to his side.

On his workbench was a gun, a bottle of aspirin, and a bunch of old pictures. He had slit his wrists with his old switchblade. Blood was diffused everywhere, his pajamas were draped in it. As I bent down, my white sandal suddenly became soaked in the crimson liquid. I panicked for a second and that's when he turned his head slightly and hissed, "I'm sorry."

"I got to call for help." I could feel myself faltering like a flickering flame of a white-hot candle.

"No" he spluttered; his breath came in ragged, shallow gasps, memories of the past swarmed all over him as the music of Lalan Shai's "Somoy Gele Sadhon Hobe Na" was rending asunder from the old radio that hung on the other side of the wall.

"It's too late" Mahmud murmured. "I'm alone; my family's far away…" he added. "All my dostos (buddies) are gone; I saw them die before me. The things we did— the things I did— are heartless, deleterious, and unforgivable."

"Don't say that" I retorted as I held his hand. His hands were inert, rough, cold, and wan now.

"The things I did," he repeated. "I'm sorry for the things I did," apologizing to me as if I had been a haunted victim of his tortuous past.

My cell phone was in my pocket as I was still in delirious doldrums. I could feel my voice breaking, my eyes welling up. He sparked into one last smile, through the thick mustache, and muttered "I'm sorry" one last time.

I stood up, transfixed; my legs were shaking and I saw the gun wasn't loaded. But he had taken gluts of aspirins as if he could not withstand the choice of having an easeful end.

Photographs of him and his old buddies from his military days lay cluttered on the floor. In one of these pictures, I could unerringly recognize a much younger Mahmud. Next to the photographs was a pile of letters in envelopes with different names. It seemed he wanted to go slowly, unnoted, and unsaid; luxuriating in his last moment with Lalon Shai.

Hasan Maruf teaches English at DPS STS School, Dhaka. His interest lies in diverse genres of literature.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments