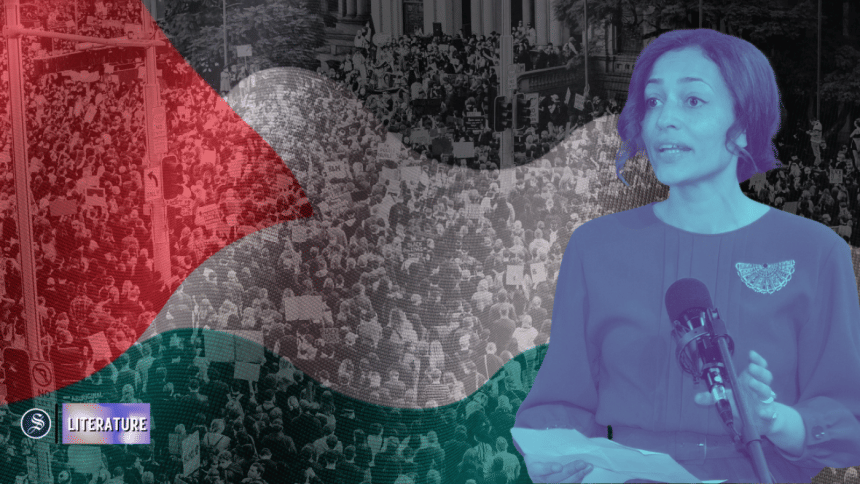

Zadie Smith’s rhetorical tricks

Zadie Smith's The New Yorker essay didn't need to happen, but it did. Try to parse out what the point of the piece is and you'll run into problems. You can reduce the few cogent points to a handful of platitudes:

-People are not a monolith

-Acknowledge the sentiments of those who say they're scared

-Histories are complex and reductive simplicity is not the right path

-Allow people to lawfully protest a cause they feel is just

The problems, however, appear when one looks at the details in Smith's words, both that she includes and those she doesn't.

Smith begins by conceptualising what she understands to be the basic principles of the protests, i.e. that you must stand by the weak, and should the machinery of oppressive power be used on the weak, you must prevent it.

I find the choice to use the word "weak" in this context very unusual, even after Smith expands it to mean "whoever suffers the most". Its vastness, and lack of real descriptiveness, allows Smith to position as weak Zionist Jewish students who feel threatened in the new atmosphere of US college campuses. It appears that in Smith's eyes, the brutality of the US police against pro-Palestine supporters does not make them the "weak" ones, i.e. the ones deserving of sympathy and our efforts. Smith also seems to forget the three Palestinian students shot at in Vermont while wearing keffiyehs, along with the former IDF soldiers throwing skunk water on pro-Palestine students in Columbia. These are both incidents that resulted in hospitalisations.

The other glaring issue of this framing is that the "weak" in each scenario are drastically different. The Jewish students who are Zionists in the US campuses and the people of Gaza losing their lives, limbs and homes are not comparable entities; they do not occupy the same category of "weak". Moreover, "weak" is a strange adjective for a people resisting an ongoing occupation for three quarters of a century.

The protests are seeking justice. Smith acknowledges that there are personal sacrifices being made by these young protestors, and if one looks at the actions of Canary Mission, it is evident that prices have been paid for pro-Palestine activism. It is the kind of empathy I expect from Smith who has shown remarkable empathy and nuance in the portrayal of the Bangladeshi immigrant community in White Teeth (Vintage, 2001), a community she is not a part of. It was a portrayal that managed to avoid the pitfalls of both stereotyping and romanticisation. The feat was more impressive considering Smith was only 25 when the novel was eventually published. In the 23 years since. Smith has published more novels that have delved into the postcolonial conditions. To then see such an article then is disappointing, and that too if one is being mild.

Smith's framing runs into the same blind spot in other criticisms levelled at student protests, i.e. it detaches the student's cause from the activists, academics, and journalists, Palestinian or otherwise, who have been documenting Israel's settler colonial project for 75 years. It is as if she isn't familiar with the works of Edward Said, Rashid Khalidi, Ilan Pape, Avi Shlaim, and Noam Chomsky. It is as if Smith believes that Hamas and the Israeli state are on a level playing field. Even more appalling is the sheer vagueness and lack of attribution to the string of horrific incidents she lists. The line about protestors wanting seven million Jews to vanish is incendiary, because it assigns violent desires to a group of people largely seeking to end what has been called "one drop in the ocean of what's going on in Palestine" by Hisham Awartani, one of the aforementioned Palestinian students, left paralysed after the shooting.

"Shibboleth" is Smith's way of saying, despite her praise of student protestors, that choosing sides is merely tribal. It is in the same category of insults hurled by frantic anti-woke mobs at the slightest dissatisfactions shown by students that the American right gleefully labels as woke to deligitmise their concerns about sociopolitical issues.

It is as Andrea Long Chu wrote in a September 2023 article discussing Smith that, "Smith has often made a virtue of negative capability, Keats's phrase for how Shakespeare wrote so empathetically that he appeared to hold, in Smith's words, 'no firm opinions or set beliefs.'" It is useful at a time when not much is known about a situation to be sure; it is useful too in fiction. This is not the case here.

Nuance can be a sign of enlightenment, the ability to be level headed in a crisis and see what many might be forgetting to look at. However, nuance can also be a sign one is detached and unaware of suffering. Sometimes nuance can mean being privileged enough to scoot between New York and London without knowing what it is like to lose your only home.

A month after 9/11, Smith wrote an article responding to James Wood's categorisation of her writing as "hysterical realism". Smith concedes. She then speaks on the impossibility of writing at such a time, with writers having "the most pointless jobs in the world" and being a "useless irritation". In the current climate, this seems bizarre. A poem is what Dr Refaat Alareer wrote for his eldest daughter Shaima as he feared his life might come to an end. Shaima has since died in an Israeli airstrike, four months after her father who died in a similar way. What has remained is the poem. Yet, Smith does not seem to know what purpose a writer serves during a crisis such as 9/11 or a genocide.

In 2021, Palestinian poet Geroge Abraham wrote "Teaching Poetry in the Palestinian Apocalypse". There too, language is held as a force with constructive and destructive possibilities, with Abraham writing, "Within this cycle, Palestinians witness repeating patterns of both-sides-isms and revisionist erasures of our struggle's ongoing memory emerging from the American media. In their syntactical patterns and use of passive voice, in every statement divorced from the transparent and well-documented reality of Israeli ethnic cleansing, in every failure to contextualise the ongoing history of Palestinian resistance, the US media contorts the English language into a supremacist enactor of the colonial project." Over two decades after Smith's October 2001 essay, Smith seems to have stopped even "trying" to understand what she might do as a writer in a world falling apart at the seams. More egregiously, she has used language to pour fuel into the tactics of a genocidal regime keen on weaponising anti-Semitism.

It is now the eighth month of the war. To make it sound as if language is being used for a narcissistic purpose-"your cause and only your cause"-and not solidarity, belies not just ignoring of vital facts but a failure of imagination. Miles apart and in conditions not the slightest bit comparable, basic human decency has pushed thousands to organise for the barest human rights of those trapped and bombed, continually, between the river and the sea.

What ultimately is the point of Smith's essay? If her views are as weightless as she claims it to be, why did she bother to write on this at all? Can we then surmise the purpose is to follow her lead and be quiet, because we are looking at groups, in her view, as a monolith? Should we stop trying to learn and stand back? What was achieved by the writing of this essay? What use is a voice in a public platform if its owner does not have the ability to see a genocide and speak against it?

In days to come, when the support for Israel dwindles, Smith's essay will serve as a reminder to be wary of hubris and disaffection at a time when hearts should be breaking. It will remind people that empathy for those facing the most horrifying conditions possible might be lost should we not educate ourselves. Lastly, it should teach writers that the simple fact of creating characters for a living does not make them capable of being sensitive to real humans outside. People have their roles to fulfil in the prevention of unfathomable atrocities, and that includes writers.

Aliza Rahman is a writer based in Dhaka. She can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments