Through the doors

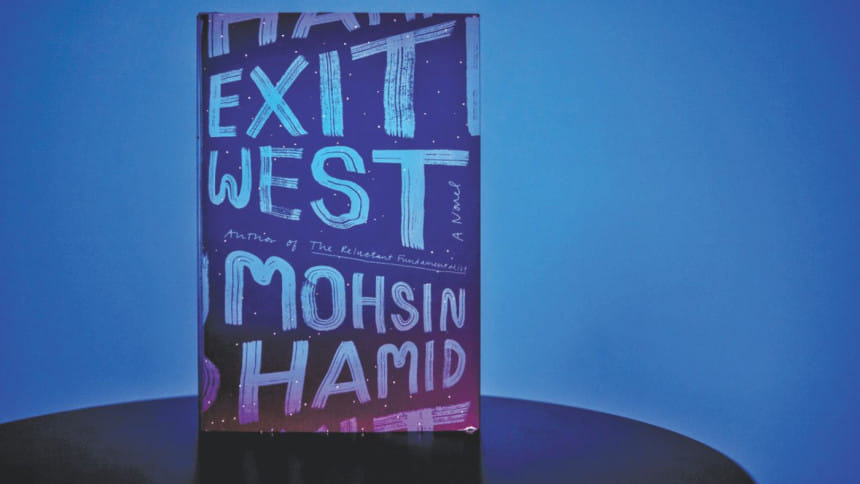

There cannot be a book more for our times than Mohsin Hamid's Exit West which came out last year, at the peak of the European migration "crisis". Hamid's earlier The Reluctant Fundamentalist too tackled contemporary issues of identity, Islamophobia, and disenchantment with US foreign policy, against the backdrop of 9/11.

Exit West on the other hand is described as "a love story from the eye of the storm", set against the backdrop of migration and the (im)permeability of borders. In an age of travel bans, fortress Europe, and a giant wall between the US and Mexico fast becoming a reality, Hamid's fourth novel takes a look at a world where magical doors pop up for those desperate to leave impoverished, war-torn cities that were their homes for new, unfamiliar shores.

But at its heart is a couple who are introduced by Hamid in his opening line, "In a city swollen by refugees but still mostly at peace, or at least not yet openly at war, a young man met a young woman and did not speak to her." Saeed and Nadia are two young, urban professionals in a city in the Muslim world; it is never really clear where they are living, but based on the descriptions, it could be a number of cities strife with violence in Syria, Libya, Afghanistan, or Hamid's own Pakistan.

Though their city is "teetering at the edge of the abyss", they eventually do speak to one another as they go about daily life working, attending evening classes, running errands, and going on dates at cafés, burger joints, and Chinese restaurants. Nadia is "always clad from the tips of her toes to the bottom of her jugular notch in a flowing black robe" but this is not imposed on her, rather she wears it "so men don't fuck with me" as she tells Saeed. She defies convention in other ways—among the two, she is the one who lives independently (Saeed lives with his parents, is devout, and chaste).

While not exactly ripped-from-the-headlines, scenes now common to us of a city descending into civil war, resonate—power cuts, gas shortages, no running water, vanishing Internet and cellphone services, and small, rushed burials. As the war nears their homes, Hamid describes the stockpiling of food, travelling through blockades, the rush to the ATMs, and at home, the barricading of windows.

Hamid doesn't sensationalise wartime and he also infuses Nadia and Saeed with agency to do something about their situation. Nadia, though keen to leave, worried about them being "at the mercy of strangers, subsistent on handouts, caged in pens like vermin." The young, in particular, learn to make their own luck and take chances with the doors they hear about rather than waiting to be killed in a war zone which no longer holds any sort of life for them. Those older, such as Saeed's father, are less eager to leave behind their homeland and loved ones—Hamid writes, "for when we migrate, we murder from our lives those we leave behind."

One thing you might expect, prominent in global headlines of the past few years, and which is missing from this tale of migration, is the journey itself. Hamid instead focuses on the lives of Saeed and Nadia in their home city and afterwards, in the cities of Mykonos, London, and Marin County. Instead, he employs a bit of magical realism to transcend borders, going directly from one city to another.

Hamid has said that his plot device, doors which pop up providing a gateway out of besieged cities to faraway cities in the West, may have been inspired by The Chronicles of Narnia and its portal to the magical world of Narnia through a wardrobe. Here too, doors pop up through which those fleeing go through, not knowing what is on the other side. Readers might wonder why Hamid chooses to sidestep the journey, a chance to live the often-treacherous journey in flimsy, overcrowded boats across the Mediterranean or the long, risky one overland across eastern Europe, with magical realism in an otherwise very real story.

For Nadia and Saeed, it leads first to a beach on the Greek island of Mykonos, where they join hundreds of other migrants in tents and lean-tos at a makeshift refugee camp. They soon learn that they are here because "the doors to richer destinations, were heavily guarded, but the doors in, the doors from poorer places, were mostly left unsecured."

Life becomes about survival—buying food and water and a tent, finding a patch of land for themselves, trying to connect with family and relatives—dire circumstances far removed from their previous lives. Increasingly strapped for funds and desperate to get off the island, a bout of luck leads them to another door.

While their circumstances are much better in this city, squatting in an expensive home in London, their reception eventually turns sour as more and more migrants keep appearing all over the city. Nativists, as Hamid calls those in the host countries, begin to turn on the migrants. Riots take place and the migrants are cut off from utilities. While Nadia tries to understand the "reclaim Britain for Britain" view of the nativists, Saeed points out that their own country had hosted war refugees of neighbouring countries. She replies, "That was different. Our country was poor. We didn't feel we had as much to lose." At the forefront of the story too, is Nadia and Saeed gradually growing apart as they journey.

Threaded through the novel are also glimpses of other unnamed people in interaction with migrants in different cities around the world which illustrates the larger picture of this global migration. One of these, an old woman in Palo Alto, California, who had lived in the same house all her life, thought herself a migrant because of the changes she had witnessed around her—that "we are all migrants through time."

Exit West is above all a study in what migrants fleeing war, poverty and dictatorship think, feel, and do when dislocated. Hamid, a migrant himself, is a fervent advocate of a world without borders, arguing that migration is a fundamental human right. In an interview to The Guardian in December 2017, he says that the world will see a movement for migrants' rights as once happened for the rights of women, African Americans and gay people.

At less than 250 pages, Exit West is a quick read. Like The Reluctant Fundamentalist ten years earlier, it too was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Unlike his earlier novels which used a narrator, Exit West has more traditional storytelling making Nadia and Saeed's story more accessible to readers.

But the novel does not end in a dystopian world overrun by migrants or the West expelling them. Rather, it is about an age-old practice that the people have used for survival and making their way in the world. Indeed, migration is the bedrock of how the US, which Nadia and Saeed's next door leads to, came to be. Exit West delves into the lives of the migrants, rather than their numbers, the flight, and rich nations facing a migration "crisis", which have taken away the spotlight from those living it.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments