In search of a development model that doesn't leave out people and the environment

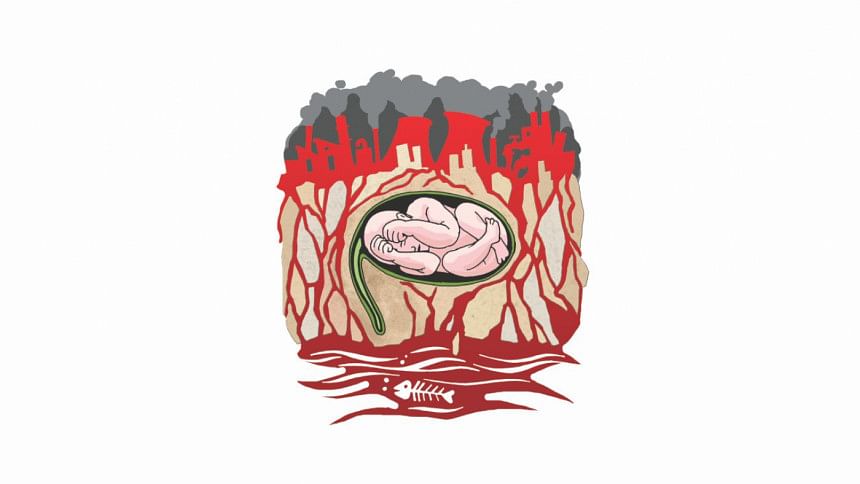

Is development essentially harmful for the environment? Must we sacrifice the environment in order to achieve much-needed development? Should we allow poisoning of our air, destruction of our forests, and pollution of our water to embrace development? If the answer is yes, how can we survive—how can this mother earth retain its ability to support our existence and our reproduction?

Is it possible to have a development model that can work in harmony with people and nature?

In fact, whether development harms the environment or creates vast opportunities to enrich human lives associated with nature depends on its prime mover. The concept of “development” does not have a homogeneous meaning; it carries different sets of ideas, and different ideas of development represents interests of different classes/sections of people—the prime mover.

In the late 18th and early 19th century, when capitalist development made its advancements visible, theorists of the classical school treated the environment as “free gifts of nature” which should be exploited for development and capital accumulation. Development economics emerged after the Second World War with a diversity of voices, but it continues to be dominated by the modernisation school which emphasises capital accumulation and profit-making endeavours without paying necessary attention to its impact on the environment. For Neo-classical economics (logically one can call it corporate economics), the environment is an external problem, an obvious side effect of economic progress; it is a problem of externality and can be solved through the market, by pricing nature. It is not interested in changing the causes of environmental degradation, because it assumes that it is a given for market expansion and private profit accumulation. This model, which has been embraced by global rulers in this age of neoliberal globalisation, looks at the environment as a commodity, and analyses the problem through its assumptions of a free competitive market and informed consumers—which, of course, do not exist.

This neoliberal model of development has been armed with flawed assumptions and rhetoric to rationalise an aggressive mode of capital accumulation, or in leftist theorist David Harvey's words, accumulation by dispossession. This model asks for privatising and corporatising public resources and public rights; it asks to deregulate monopoly capital; it asks to commercialise everything including public services. In this model, market growth and maximisation of profit are considered as sacred objectives of development; human, social and environmental costs are seen as inevitable. This model does not allow for any critical examination, because as they say, there is no alternative (TINA). But there are much better alternatives.

Other theories of development have also emerged which consider the environment a very important component of development. As early as the 19th century, Karl Marx, while critically addressing the classical school of economics, opined that the aggressive exploitation of nature would certainly affect the larger universal metabolism. Marxist sociologist, John Bellamy Foster, who writes about political economy of capitalism and economic crisis, ecology, and ecological crisis, further explained that “the antagonistic form of capitalist production—treating natural boundaries as mere barriers to be surmounted—led inexorably to a metabolic rift, systematically undermining the ecological foundations of human existence.”

Nearly three decades ago, the Brundtland Commission, established by the United Nations in the 1980s, to rally countries to work and pursue sustainable development together, released “Our Common Future” in October 1987—a document which coined, and defined the meaning of the term "Sustainable Development". It defined “environment” as “where we live” and development as “what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode”. The report was also very clear in stating that these “two are inseparable”.

In September 2015, heads of states and governments from all over the world gathered at the UN headquarters in New York to finalise sustainable development goals (SDG) for every country in the world, including Bangladesh. In the end, they reached a common declaration. Let me quote a few relevant points of the declaration here:

• “We envisage a world in which every country enjoys sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth and decent work for all.

• A world in which consumption and production patterns and use of all natural resources—from air to land, from rivers, lakes and aquifers to oceans and seas—are sustainable.

• One in which democracy, good governance and the rule of law as well as an enabling environment at national and international levels, are essential for sustainable development, including sustained and inclusive economic growth, social development, environmental protection and the eradication of poverty and hunger.

• One in which development and the application of technology are climate-sensitive, respect biodiversity and are resilient. One in which humanity lives in harmony with nature and in which wildlife and other living species are protected.”

Despite these promises, there is no sign of any significant change in the dominant development model that has been taking the world in an opposite and dangerous direction. For Bangladesh, in particular, the scenario is worse. Our so-called development partners, international financial institutions and other hawkers of the neoliberal development model are still pushing for projects that can only be described as projects of mass destruction. In Bangladesh, the dead or injured bodies of rivers and forests, and rapidly shrinking wet lands and open spaces bear testimony to the short-sightedness of many foreign-aided development projects.

It is often claimed by these “development” contractors that economic growth should be the most important goal of development. Because, in their view, economic growth, even when it causes harm to the environment, can ensure “peoples' interest”—their employment, income, and future security. Some also suggest that the environment is a luxury; people first need food and jobs, and therefore, development should get priority over the environment in underdeveloped countries. They systemically hide the real cost of these development projects, in particular the environmental and social costs. They consciously hide the increasing number of uprooted people because of the development projects they advocate. They turn a blind eye to the growing population of environmental refugees or environmental proletariats which have resulted from the “development” march.

The wholesale privatisation of natural resources, grabbing of common property including rivers, forests, and open spaces, dismantling of national capability and implementation of projects of mass destruction have become the dominant features of the present “highway to development”. Such an economic model inevitably causes destruction of agricultural land and water systems, loss of fertility and crops, damage to eco-systems and fish production, health crisis eviction of communities, and rural to urban migration. Coal-fired power plants that threaten the survival of the Sundarbans and the coastal ecological system; open pit mining projects that destroy fertile lands, underground water resources and evict millions of people; and nuclear power plants with high debt and high risk are high priority projects that are being pursued in the name of development.

While subsequent governments of Bangladesh have been pursuing corporate-controlled, private profit-centric, debt dependent and environmentally disastrous energy and power policy, a strong democratic people's movement has also emerged to resist this. The movement, on the one hand, popularises the demand to scrap anti-people and anti-environment deals, and on the other, advances the vision of equity, pro-environment energy justice and pro-people technological advancement. It shows that cheaper, healthy, environment-friendly sustainable power generation is possible. Projects like Rampal coal power plant and Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant are not at all needed to fulfil the power demand of the country. There are much better, attainable alternatives. (See for details: http://ncbd.org/ wp-content/uploads/2018/01/ The-Alternative-Power-and-Energy-Plan-for-Bangladesh-by-NCBD.pdf)

Similar exercises can be done for other areas as well. However, we should not forget that economic policies and the development process cannot be independent of politics and the hegemonic, ideological vision of the powers-that-be. The struggle to change the power balance in favour of many against a few, in favour of people against corporate grabbers, in favour of the environment against destruction must be inseparable from a counter-hegemonic vision of the people, in order to make a new development into a reality.

Anu Muhammad is Professor of Economics, Jahangirnagar University. Email: [email protected]

Comments