Ghosts of 1947

Bangladesh stands out in postcolonial South Asia for its strikingly anomalous relationship to what neighbours consider to be the foundational event in the region's modern history—the 1947 partition of British India. Official acknowledgement—celebratory or otherwise—is notable for its absence. Unofficial spaces are hardly more forthcoming. In the weeks leading up to the 50th anniversary of the Indian and Pakistani independence, I was struck by the seeming irrelevance of a moment that in other national contexts appeared to be profoundly meaningful. BBC World and CNN International, cable channels available to audiences here, devoted extensive coverage to related events. In contrast, Bangladeshi media outlets exhibited a muted interest or ignored the anniversary altogether. Two decades later, things have changed somewhat. This special issue is testament to that. Still, significant silences persist, and extend to the realm of scholarship and popular culture. Public recognition of 1947 in collective memory and in institutional sites continues to be subdued at best.

" It is my contention that 1947 does not merit remembrance, let alone celebration, because to address it directly would be to unsettle a carefully constructed teleology of Bengali nationhood. That is, the unconscious erasure of partition is an attempt to gloss over the incongruous, to banish memories, desires and narratives that sit awkwardly with an ostensibly unifying national story.

What accounts for this apparent indifference? Most obviously, the country's relationship to the 1947 partition is mediated by the events of 1971 so that—arguably—the significance of the latter overwhelms any attention to the former. By this logic, the partition may well have lost relevance for contemporary Bangladeshi reality. This is an inadequate explanation. It does not shed light, for instance, on the curious neglect or outright erasure of partition that marks nationalist narratives and historiography.

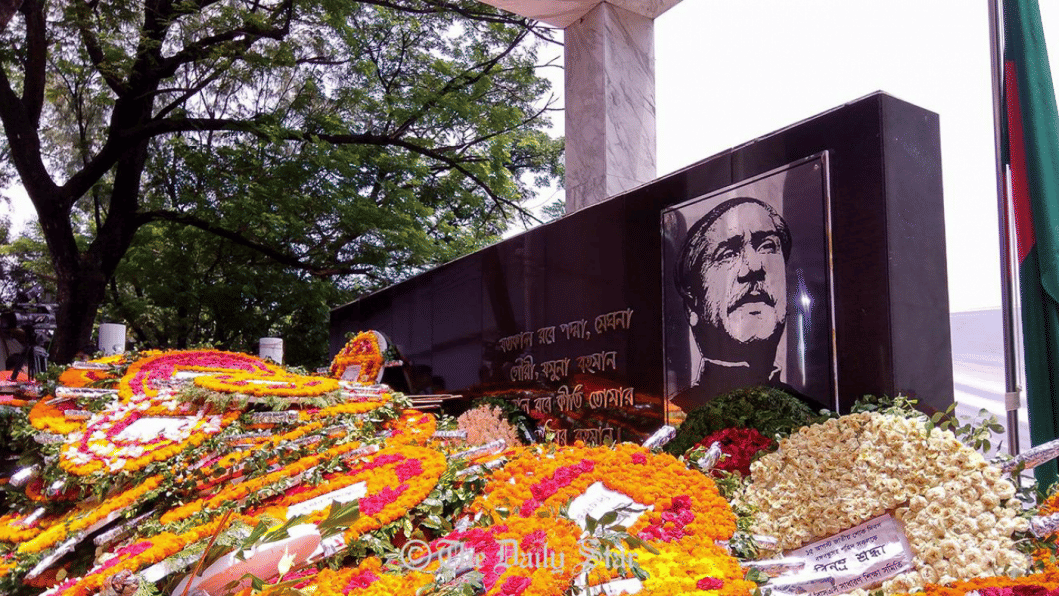

Of course, the events of 1975 irreversibly changed the set of associations with August 15. It is probably not incidental that this was the date that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was gunned down in a military coup. The symbolism of eliminating the official 'Father of the Nation,' one who embodied the aspirations of the secular Bengali intelligentsia, on that particular date surely did not escape his killers. The timing of this brutal act may well have signified to the killers the smashing of a specific social order, one premised on the aspirations of Independence in 1947. We will never know for sure, but the irrevocable shift in meaning ensured that August 15 could never be a day of celebration in Bangladesh. Or so it seemed. When the Awami League finally returned to power in 1996, the Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina declared it a day of official mourning, a national holiday. In an extraordinary and some would say spiteful gesture, the BNP's Khaleda Zia, upon coming to power several years later, began to celebrate her official birthday on that date. By decree, the meaning of the 15th changed overnight. From a day of national mourning, it was reduced to a mocking spectacle of coerced official celebrations marked by elaborate public rituals of cake cutting and congratulatory messages. This overt move to re-signify the meaning of August 15 was reversed after Sheikh Hasina's return to power.

Clearly, preoccupation with August 15 in Bangladesh occupies a distinctive field of signification, fundamentally unrelated to discourses of partition/independence elsewhere. There is more to the story, however.

Haunted by History

It is my contention that 1947 does not merit remembrance, let alone celebration, because to address it directly would be to unsettle a carefully constructed teleology of Bengali nationhood. That is, the unconscious erasure of partition is an attempt to gloss over the incongruous, to banish memories, desires and narratives that sit awkwardly with an ostensibly unifying national story. In other words, it is the need for an active forgetting of certain fractious histories that renders the historiography of Bangladesh askew of the rest of the subcontinent. Within this normative nationalist framework (even with competing versions), 1947 cannot constitute true independence. Rather it denotes one more moment in the continuing history of (Muslim) Bengal's colonial domination, marking the transfer of power from the British to the West Pakistanis. Thus, historians of Bangladesh routinely refer to the double cloak of colonialism. The official timeline of the nation nods to 1905, and moves on to 1952 (the inauguration of the language movement) as a foundational moment.

But why sidestep partition? What is it that must not be remembered? And what is missed or papered over in the process? Arguably, the singularity of Bengali nationalism cannot but disavow 1947 because from a Bangladeshi national perspective, partition's twin is not Independence but (East) Pakistan. Here in lies the problem. Much of the ambivalence around nationhood and identity in Bangladesh, I suggest, can be traced to ambiguities in the meaning of Pakistan for Bengal's Muslims when it was created. It was in this context that the 1971 war disrupted, displaced and reconstituted older meanings of partition, and so of Pakistan. After the fact, the only official meaning of Pakistan that endured is as an essentially/exclusively Muslim place.

Consequently, the memory of East Pakistan occupies an uncomfortable space, one that must be disappeared in critical ways. Put differently, it is the irresolution of the Muslim question, and so of the question of what national culture looks like, that haunts the national project. Here it is worth recalling Irfan Ahmed's provocative proposition that partition was not a solution to but an escape from 'the Muslim question.' If the creation of Pakistan cast out and amplified the question, the emergence of Bangladesh provided only temporary reprieve.

" What would it mean to decolonise the study of partition in present day Bangladesh? One way would be to address directly the many submerged meanings of partition beyond the rhetoric of loss, horror and dismemberment.

Thus, no version of the national story can accommodate, for instance, the Bengali-speaking (Muslim and namasudra) peasantry's enthusiasm for Pakistan as documented by Ahmed Kamal, Taj Hashmi and others. Nor can it absorb more complicated interpretations of the so-called double cloak of colonialism. For instance, some Bangladeshis refer to 1947 as the first independence, meaning that Bengal's subaltern classes (again, Muslim and non-Muslim) had to first separate from upper caste Hindu domination, before they could be truly independent (Gautam Ghosh, personal communication).

Here we see how nationalist desire for narrative permanence and fixity of territory and identity invariably comes into tension with the contingencies and complexities of identity/border making in practice. The conventional Hindu versus Muslim storyline simply does not stand up to scrutiny. Yet readings of partition, even when they are critical, tend to share certain assumptions with the two-nation theory. Hindus and Muslims are understood to represent pre-constituted and separate communities, for whom religion is foundational to identity. Class, caste, region and other distinctions are subordinated or deemed irrelevant. In contrast, the ideological moorings of Bangladesh's nationalism are grounded in assumptions of a priori secular Bengali subjectivity, one that refuses religious distinctions. By extension, 'the Bengali' is conceptually pitted against 'the Muslim,' thereby reproducing a standard explanation for partition. Conventional historiography is trapped: histories of communal tension and class fractions are difficult to accommodate within the existing terms of debate.

The subsequent muting of 1947, its excision forom official memory, cannot but haunt the national project. The periodic emergence of partition's ghosts, I contend, is a central feature of Bengali/Bangladeshi nationalism. Especially at moments of crisis, the 'ghosts' of other submerged histories escape through cracks in the story of nationalism. Invisible but contentious histories—whether it is of the Bengali-speaking peasantry who turned to census operations to be classified as namasudras, or non-Bengali urban proletariat displaced by the 1946 Bihar riots—continue to shape community and nation-making practices. Reading the history of 1971 without taking into account 1947 does not simply produce incomplete histories; such a move obscures the historically constitutive processes through which categories of (national) Self and Other are produced and normalised, and the dynamics that allow for the privileging of some narrative accounts and simultaneous displacement of others. Put differently, the inability of Bangladeshi nationalist historiography to come to terms with partition/Pakistan ensures the return of the 'Muslim question.'

Decolonising narratives of nostalgia

Although predominantly focused on the Punjab border, and on the experiences of refugees from East Bengal to West Bengal, the Indo-Pakistani model of loss and nostalgia dominates emerging research on partition in East Bengal (with notable exceptions). Curiously, the experience of Muslim-Bengalis compelled to or who 'opted' to relocate from West to East Bengal has yet to be documented systematically. It is telling that the numerous accounts of such experience, scattered in novels and political memoirs, are rarely articulated in terms of loss/nostalgia or forced displacement.

What would it mean to decolonise the study of partition in present day Bangladesh? One way would be to address directly the many submerged meanings of partition beyond the rhetoric of loss, horror and dismemberment. It would be to ask what the stakes are in recalling that for the (predominantly but not exclusively Muslim) peasantry, the new nation represented not so much a homeland for the region's Muslims as the possibility for a new start through the dismantling of economic oppression and religious/social discrimination. It would be to document but also go beyond the many informal stories in circulation of families divided across multiple national borders, and the pain and absurdities this entailed, to confront questions of class, inequality and property relations. The 1947 partition provided affluent Muslims in East Bengal with an unprecedented opportunity to reconfigure socio-economic relations in a landscape previously dominated by upper caste Hindus. It has been suggested that the large-scale appropriation of Hindu land by Muslims that took place at the time encourages contemporary silence around partition. This is not an unreasonable line of thought except that it assumes all 'Hindus' have identical interests. A decolonised partition narrative would ask how and why the caste question was erased from mainstream accounts of 1947, and to what end (Chatterji; Sen). It would also take on board striking silences such as that around Jogendranath Mandal's role in Babasaheb Ambedkar's election to the Constituent Assembly from the Bengal Province in 1946. By extension, we would have to ask why the 'Land of Eternal Eid' descended so rapidly into a realm of hostility and expropriation for non-Muslims. Why did Mandal, Pakistan's first law minister, resign in such despair?

Finally, a decolonial analysis calls for vigilance against the inherited (from colonial and some Indian nationalist thought) animosity toward Islam and Muslim political leaders of the time. Despite evidence to the contrary, why are leaders like Suhrawardy 'mis-remembered' in public culture especially since he was able to imagine a United Bengal in which Bengaliness did not preclude being Muslim (Bhattacharjee)? Why are the likes of Bhashani and Abul Hashim figures of great ambivalence and discomfort today?

Decolonising our imaginations begins with denationalising the writing of history; we must turn our attention to questions of framing and narrative structure, of why partition stories are told the way they are, in order to unmask the workings of power. The task then is to dismantle the oppositions and taken for granted narratives (partition as the result of religious animosity engineered from the top or the putative tendencies of Muslims toward separatism) through which we have come to understand our histories and our possible futures.

Dr Dina M Siddiqi divides her time between New York and Bangladesh, where she is Professor of Anthropology at BRAC University. She is currently a fellow at the Center for the Study of Social Difference (CSSD) , Columbia University, New York.

References

Irfan Ahmad 'Modernity and Its Outcast: The Why and How of India's Partition.' South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 2012.

Dharitri Bhattacharjee 'Mis-remembering History: Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy's United Bengal Plan That Could Have Changed the Course of Indian History.' The Wire 15/8/2017

Joya Chatterji The Spoils of Partition: Bengal and India 1947-1967. 2007

Dwaipayan Sen 'Caste Politics and Partition in South Asian History.' History Compass, 2012.

Dina Siddiqi 'Left Behind by the Nation: 'Stranded Pakistanis' in Bangladesh. Sites, 2013.

Comments