Looking at 'Gujob' Hypothesis

Gujob, a word that has been repeatedly used by pro-government supporters online to lambast any critical view of the government, has made a sudden comeback this election period—after an official post by Facebook, the social media mammoth with the highest number of active Bangladeshi users, announced the thwarting of an attempt at a misinformation campaign by disabling nine Facebook pages and six Facebook accounts. Twitter, another popular social media, announced that they too suspended 15 accounts for 'coordinated platform manipulation'.

Let's pause for a bit. This is not new. We have seen a steady-rise of 'gujob'—or 'fake news' (as US President Trump terms it)—in the last two-three years. What was the big deal this time? Well, there are several things you need to take into account.

Firstly, the timing: Bangladeshi elections are just around the corner and the volatile political situation has already made international headlines. Facebook, during the US elections couple of years back, was criticised for its dubious role in containing the spread of misinformation. Apparently learning from its mistakes, Facebook proceeded to amp up its game: it is now more vigilant and has taken several pre-emptive measures to not repeat the same kind of incidents. Surely, they would want to boast about their new-found capabilities to avoid a future maelstrom.

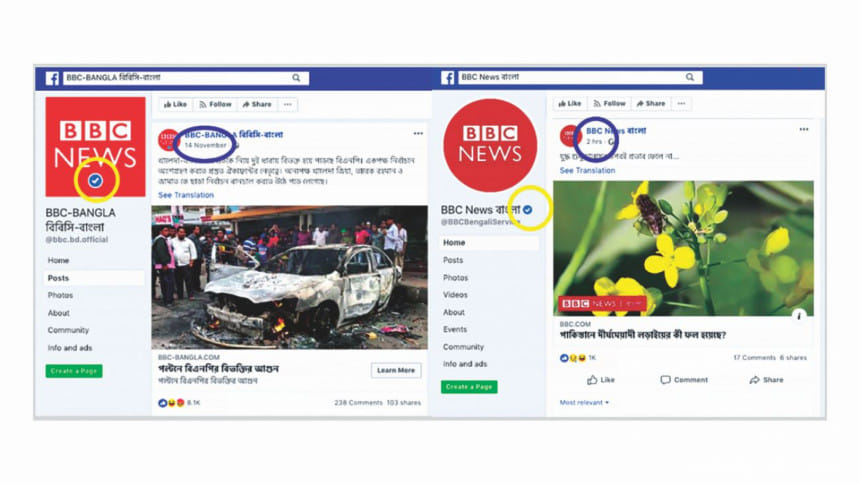

Secondly, the content of the posts made and shared by the accounts and pages in question: both Twitter and Facebook informed in their releases that the content were 'pro-government and anti-opposition' in nature. The design of the content and construction of the language were awfully similar to some of the locally popular news outlets. But, most of the news content was fake and was clearly designed to instigate agitation among opposition followers and activists.

Thirdly, the activities of the pages and accounts that were taken down: the misinformation as well as the activities of the accounts were well thought-out. According to Facebook, at least one of the pages had 11,900 followers and had an overall ad spending of USD 800 (roughly around BDT 65,000). The first ad campaign was run in November 2017 (more than a year ahead of the election) while the last one was run in December 2018. On Twitter, the followers were low in number for the accounts—which is proportional to the number of users Twitter has in Bangladesh. The disabled account with the highest followers were a little shy of 50 in number.

Lastly and most importantly, the people behind these: so far Twitter and Facebook both have pointed their fingers towards 'a state sponsored actor'. Their claims came after extensive analysis and verification by Graphika (a social media threat assessment company that also helped investigate Russian involvement in the US elections) and Atlantic Council (a US based think-tank).

So what do all these facts add up to? Quite frankly they add up to one word: hypocrisy. While the government is continuously running awareness campaigns against fake news and misinformation, a portion is trying to create smoke screens for their own advantage.

Rapid Action Battalion and cyber squads of other law enforcement agencies are currently running ads and campaigns to stop the spread of rumours—while monitoring online content at the same time—with a budget of TK 126 crores, approved by the Executive Committee of the National Economic Council (ECNEC) on November 4, 2018. Coincidentally, half of the fake news pages taken down by Facebook were created just a week after the approval of this budget.

What are the implications of these gujob (fake news)? One thing is for sure, while all the local law enforcement agencies are actively working to make our social and online space 'gujob-free', a handful of pro-government sites were able to make their way through and amass a tiny bit of traction. Was this a test-run for a future full-blown campaign? According to the Atlantic Council, the people behind it saw an opportunity coming and tried to run a slightly less-coordinated campaign by devoting a small amount of resources to understand the impact.

With the polls looming, let's hope everyone uses their common sense and better judgement before getting themselves sucked in by all the 'gujob' out there.

Shahriar Rahman is In-charge, Bytes, The Daily Star

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments