Illuminate the Blind Spot

Sajedul Islam Ratul is a second-year student in Dhaka University's political science department. In a batch of around 120 students, Ratul is the only one who is visually impaired. His journey to Dhaka University, the country's highest seat of learning, from Kishoreganj is an odyssey of overcoming one hurdle after another. Buying rare and expensive Braille books, prevailing over the reluctance of school and college authorities to enrol him due to his disability and finding people to write on his behalf during public exams are some of the challenges he has had to overcome to gain admission.

“I was determined to overcome all the challenges at any cost to qualify. This was the only way I would be able to get a good job to help my poor parents,” says Ratul.

After admission to DU last year, just when Ratul was beginning to feel confident that he was getting closer to his dream of becoming self-sufficient, he faced one of the biggest and most unexpected obstacles—one which remains unsolved. “I found that there are only two reference books in my subject available in Braille in our central library. However, our teachers regularly give us assignments from different journals, asking us to read and analyse articles published in newspapers and on different websites.”

Besides, Ratul feels that it is extremely important for him to read various newspapers regularly on the internet to keep up to date with current affairs—a primary requirement for qualifying in job exams and in his discipline. Unfortunately, Ratul cannot access any Bengali texts online.

“Us visually impaired people have no way to read any digital Bengali texts unless and until someone reads it aloud or it is available in Braille. We can only access English materials using screen reader applications but these tools, which have been developed in foreign countries, cannot read out Bengali texts,” adds Ratul.

Dr Diba Hossain, Professor, Institute of Education and Research, University of Dhaka has been conducting research on the educational development of visually impaired students for more than three decades. “We need to develop an accurate Bengali text-to-speech converter and optical character recognition (OCR) applications. With the help of an accurate Bengali text-to-speech converter, a visually impaired student will be able to access digital texts in all formats, whether published on a website, Word document or in a PDF format. And OCR is an essential tool in converting digital Bengali texts into Braille,” she says.

“Due to the unavailability of these tools, visually impaired students in Bangladesh have to depend solely on a handful of reference books which are occasionally printed in Braille by some charitable organisations. Meanwhile, their sighted classmates are learning from the internet, newspapers, journals and a lot of different literatures,” adds Dr Diba.

Over the last decade, several initiatives were taken to develop Bengali text-to-speech converter and OCR software. However, resource constraints and lack of continuation have halted most of these initiatives. The most recent and most successful one was by a Bangladeshi organisation called 'Team Engine'. Ashiqur Rahman Amit, managing director of Innovation Garage, was the project advisor of Team Engine.

“Developing a Bengali text-to-speech converter is a really challenging task because there is no corpus of Bengali words. Again, there are many consonant conjuncts in Bengali which are very difficult to convert into correct speech,” Amit says.

“On the other hand, our OCR could translate properly scanned Bengali texts into word document format with 90 percent accuracy. But it could translate poorly scanned Bengali texts with only 50 to 55 percent accuracy. Again, it could not translate scanned Bengali texts into Bijoy or similar fonts widely used for publications,” adds Amit.

However, he informs that theI CT division of the Ministry of Post, Telecommunication and Information Technology purchased the applications made by Team Engine and is working to develop these by resolving the existing limitations.

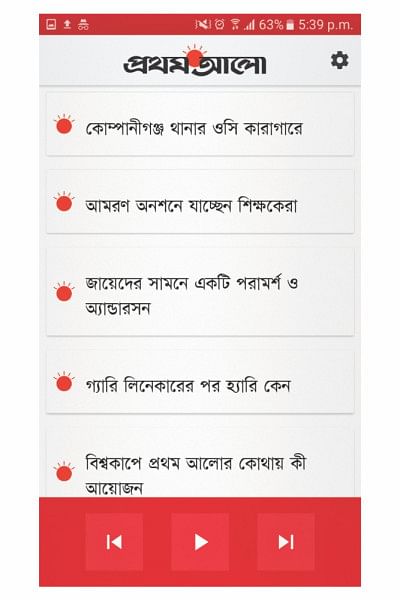

While developers are still struggling to develop an efficient OCR and Bengali text-to-speech converter, Bengali daily Prothom Alo has recently made a remarkable breakthrough. Using Google's text-to-speech converter, Q M Ashfaq Ali, assistant manager of digital technology at Prothom Alo, has developed an Android app which can read news reports published in the app with accurate pronunciation, punctuation and intonations. The app is called 'Prothom Alo Sruti', which means 'listening' in English.

Selim Khan, editor of the overseas edition of Prothom Alo, says: “Previously, we had developed another feature to reach our visually impaired readers with an audio version of our reports and columns. Unfortunately, we could not continue it due to technical errors. We have launched this new Android app this year on January 4, on the birth anniversary of Louis Braille, the inventor of the Braille system of reading and writing. Before launching this app we had invited visually impaired people and relevant experts to assess its usability.”

When Ratul was informed about this app, he was overwhelmed with joy and excitement. He downloaded the app and called many of his friends instantly and told them to do the same. “The app is excellent. The quality of voice, pronunciation, pauses between headlines and detailed reports made it quite user-friendly.”

However, when Ratul and his friends learned that Prothom Alo could update the app with only 20 of their selected latest reports, there was a bit of disappointment. “I hope they will be able to upload all the reports on the app very soon. I wish all other newspapers develop such apps for us,” says Ratul.

“We are trying to develop the app further so that we can upload more reports at a time. Also, we are working to include a voice-typing feature so that visually impaired users can comment on reports just by talking to their smart phones,” says Ashfaq.

Shah Alamgir, director general of Press Institute of Bangladesh, appreciates this initiative taken by Prothom Alo. “If we want to make media outlets accessible to disabled people we need technological assistance. Only ICT-based solutions can make media accessible to disabled people. Manual solutions like publishing Braille editions of newspapers for a small group of people will be too expensive and not viable for newspaper owners.”

However, in Bangladesh, visually impaired people are not a small group. According to a 2010 study by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB), approximately 800,000 Bangladeshis are blind. Around 13.8 percent of the country's people aged 30 or more suffer from low vision. The report further states that every year, 22 percent of newborns face extreme risk of retinopathy of prematurity, which is one of the main causes of blindness.

And globally, a person becomes blind every five seconds and every minute one child goes blind. Although no survey regarding the prevalence of visual impairment in Bangladesh was conducted in the last eight years, it is apparent from the study that every year, the number of persons with visual impairments must be increasing significantly in the country.

Bangladesh's visually impaired are some of the worst victims of negligence and marginalisation. Very few can overcome intense social and practical barriers to continue their education. Even if they rise above those challenges, our negligence in ensuring their universal right to access knowledge in their mother tongue has further curbed their immense potential.

The writer can be contacted at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments