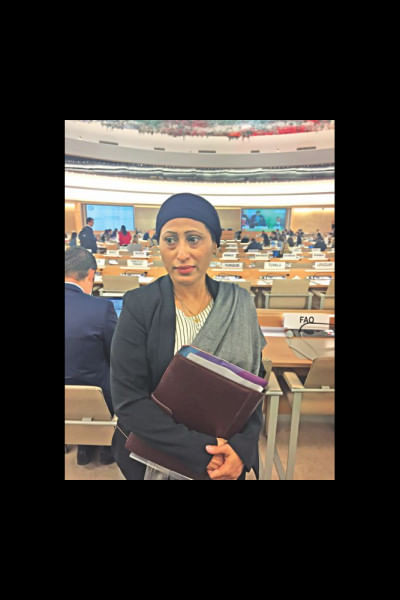

Witness to Horror: In conversation with advocate Razia Sultana

Razia Sultana is a Rohingya lawyer and educator in Bangladesh. She is currently one of 16 women activists featured by the Nobel Women's Initiative for their work as change makers in their societies. In two reports for the Kaladan Press Network—"Witness to Horror" in February 2017 and "Rape by Command" in February 2018—she interviewed Rohingya women refugees and rape survivors who fled to Bangladesh following state sponsored violence in Rakhine, Myanmar. According to her research, the perpetrators raped over 300 women and girls in 17 villages in Rakhine, but she states that the overall number is likely to be much higher.

Born in Maungdaw, Rakhine, you have lived in Bangladesh since your childhood. How was it growing up as a Rohingya in Chittagong?

Since the 1960s, my father, one of three brothers, traded here in Chittagong. The family business had an office in Amin Market [in Khatungonj], which is still here. They were used to travelling to and from Chittagong for work and eventually moved here permanently in 1968.

My father, at the time, was going to leave either for Bangladesh or elsewhere. His godown [warehouse] had burned down and when he went to claim compensation, he was denied justice. We felt our powerlessness as a minority. There had been many such incidents and restrictions which finally forced my father to leave. Since moving here, my family has never gone back to Burma. By then, Bangladesh had gained independence and it was peaceful, so our family decided to stay here.

We grew up a bit isolated from those around us. We could not easily mingle with or marry those outside our community. The first time I made Bengali friends was in college.

Why did you decide to be a lawyer?

It was my ambition. I told my father that I wanted to be a lawyer the day I graduated from college. At first, he told me that I could study law but I probably wouldn't be able to practice in this country. He later gave permission but after one year of studies, I couldn't continue because I was married by then. Twelve years later, I got readmitted. I finally became a lawyer in 2012.

How did you become involved in documenting the widespread sexual violence committed against the Rohingya?

I was a member of Arakan Rohingya National Organisation, among others, and was actively involved as a social worker in the Rohingya community. In 2012, I first joined work at the advocacy level. At a seminar in Bangkok, I met a Burmese activist who showed me some books and reports on the state of the Kachin and Shan [minorities in Myanmar]. I was shocked. Before then, I hadn't known the extent of discrimination against other minorities. Violence against women was common there as well. "Witness to Horror"originated from there—I too wanted to do what they did, for the Rohingya.

2016 was a milestone year for me. Earlier when gathering testimonies, I would also hear of people being victims of discrimination or violence, but this deliberate targeting of women was not yet noticeable. I would come across one rape victim ora woman who had suffered sexual harassment, out of say, 50. In the 2016 influx, at least one in every two women I interviewed had such a story—of being harassed, raped, or losing a family member. I decided I had to do something, especially for the women.

We set up interviews with a number of women refugees which ultimately led to "Witness to Horror" [a report with detailed testimonies of 21 Rohingya women who fled following the military "clearance" operations since October 2016]. At the time, many of the women refugees I interviewed were living on the streets [of Cox's Bazar and Teknaf].

I became ill at one point, especially when the women told me of what happened to the children in the violence. I could not stand it and I had to go to counseling myself. The rape victims were very strong, to be able to tell me their stories. Many had never received treatment after their ordeals.

One 18-year-old Rohingya girl, when asked how many men had raped her, said, "Only three."

In April this year, you spoke at the UN Security Council's open debate on sexual violence in conflict, representing civil society. What needs to be done now?

I have worked with the UN fact-finding mission and I'm satisfied with our collective work. Since 2012, we have been trying to prove that what is happening [in Rakhine] is genocide. We have at least got that recognition—one that can no longer be denied.

Now is the time for action. Everything is as clear as water; atrocities have happened, genocide is ongoing. How many more investigations will there be? How many more groups will go? How many more formalities? From the UN to Amnesty to ground-level activists, there has been more than enough evidence collected. Especially, the satellite images taken by Human Rights Watch [showing hundreds of burned down Rohingya villages in Rakhine] cannot be denied in anyway.

What work does your organisation, the Rohingya Women Welfare Society, do?

I founded it in 2017. I run awareness programmes on trafficking and child marriage. Most cases of trafficking we see are not forced—many are lured with the promise of jobs, marriage or a better life.

I have organised a group of 60 women who do home visits and counsel 500 other women. When I go to the camps, I do counselling and am confident that the women I work with directly will not fall prey to these. They in turn will counsel the others.

Regarding family planning, we approach the issue indirectly because many families are very conservative (early marriage, on the other hand, we discuss openly with parents). For me, Bangladesh is a role model in family planning. I have seen with my own eyes how family planning methods have been adopted here. If they can do it, why not us?

What legal recourse do the Rohingya have for crimes committed against them in the camps?

None. They are not refugees, otherwise they would have been protected under international law, nor are they Bangladeshis—they have no address. There is little to no legal protection for them, and very few cases are referred to the police. Many of my relatives live in the refugee camps. I have visited them but they don't encourage me to come. This life is not for them, not for anyone.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments