Letter to My Dictator

Dear Mr President,

On a terribly warm night in November, I sat on my couch, alone in Bangkok, and switched off my phone. If it was true, I wanted to see it. But if I saw it, I didn't want to talk about it. I had no way of knowing how I would react to the end of an era, your era, but I was almost certain I wouldn't share the unbridled joy of your (my) countrymen. Hope maybe, and perhaps even relief, but joy I knew not to expect.

What an era you have had Mr President! Is it even an era if it lasts 37 years?

I cannot recall the beginning, for I was not born, but you exist in my earliest memories. Much of my consciousness from this beginning is constructed— borrowed from my parents—but you lie along the creases of my imagination, hoping not to be disturbed.

My father likes to tell a story about the time my mother never spoke to him for two weeks. They had just arrived in Zimbabwe; and with no international experience and two children between them, she was convinced it was a mistake. She had always been close to her own father and her mother's role as our primary caregiver allowed her to be an accidental parent. She felt no fondness thus for the 50-hour journey into the wilderness (literally) that she would have to make or the destination she would reach at the end of it.

When we reached your city, our first company house was on a road leading away from Bishop Gaul Avenue. A sprawling two acres set in landscaped gardens, but as you will remember, Mr President, Harare was at the time expanding at the waistline. Although it was growing rapidly outwards, the city had not yet reached our area and my mother spent her nights lying awake, listening to the deafening silence of no life around us and the days sitting, and forcing us to sit, outside on the porch with her. In later years, she would grow accustomed to houses with swimming pools and orchards and tennis courts, but in those first few weeks, the space and privacy stifled her.

She tells me that she cried a lot during this time. Cried in anguish at finding herself in this land of obscurity where she neither spoke the language nor enjoyed the food. What sort of country was it anyway that didn't have the rice that she needed to make pilaf? Or any manner of fish whatsoever? Your landlocked borders were a culinary nightmare for my Bengali parents and you cannot fault them there. She cried in anguish too for the family she had left behind, the brothers and their wives, who all shared the same house. For the cacophony of 100 million souls pressing, prying, vying against each other for life and lung.

And she cried in anger at the husband who had wrangled her from all of that for a new life she did not know how to begin.

But on one of these afternoons, when my sister and I were playing on the porch and my mother was lost in a depression we did not recognise, I tripped and fell. At 30 months, I had developed instincts, but maybe not intellect, and I tried to break my fall by grabbing onto a cactus. The primal urges of a parent overtook the cold shoulder of a spouse and my mother was forced to call my father at work and ask him to drive us to the hospital. I think, Mr President, this may have been the inflection point for a woman who proceeded to fall devastatingly in love with your country.

She marveled at the skill your hospital staff deployed in extracting more than 100 thorns from her daughter's tiny palm. But also at the sheer handsomeness of your infrastructure. Your hospitals were a sight for sore eyes and your roads, in mint condition, canopied by greenery. I am not sure my mother was prepared, or willing to accept, that the city she had vowed to despise could be so beautiful. Or so organised. Your urban planners had been meticulous in their outward march, placing the uncongested business district at the heart of your capital and the residential areas spiraling in increasing radius around it. Each was fitted with a school, a doctor's chamber, a supermarket and a park. Ours had a natural creek with deer and swans we could feed.

It led up to our first school—the one which my parents spent less than an hour enrolling us into. How refreshing it must have been for them to know they did not have options with our early education; that every child was required by law to go to the school in his or her locality. And how refreshing it must have been, that absence of competition. Your schooling system—the best on your continent—was standardised to ensure quality and your curriculum favoured the nurturing of well-rounded human beings over academic accomplishment. With only four subjects and no homework until the age of 12, you disallowed the educational burdens that terrorise young minds and arrest creativity.

As my sister and I found familiarity in our school routines, our parents developed a routine of their own. More Bengalis, from either side of Bengal, had by then reached the southern tip of Africa, arriving in droves of architects, engineers and doctors. We became one big family, Mr President, undivided by background as we would have been at “home” and unclaimed by political identities as some communities are abroad. Our parents congregated every evening, in different permutations at different locations and we never left without dinner. Mothers are masters at improvising as only mothers can and they learned to manipulate their ingredients into imitating their childhood palates. We were raised on mishti made from scratch and bhorta that was pungent and at the end of every month, we knew how to sit quietly as they took us to the consulate when the Bangla paper arrived. They humphed and huddled over stale, outdated news and bonded in their collective fear over ever-rising crime in Bangladesh. Maids killing housewives and robbers stabbing students; but what did we know, Mr President? In our cocoon which you loomed over with your iron fist, crime was a work of fiction.

What was it then that converted my mother? Your well-planned infrastructure or your impeccable social services? Was it that she now had friends with whom she shared heritage? 21, 26 and 16 are important dates in my parents' history and in your land of acceptance and freedom of expression, they were able to celebrate every last one. We had rehearsals every evening from a month in advance and bleeding red and green, our fathers stayed up all night building backdrops for our events while our mothers connived to fit adult jamdanis on non-adult children. Was it this, this new-found sense of belonging, Mr President, or was it actually her admiration for her adopted people? Your people. Vanhu venyu. I use no hyperbole when I tell you that the Zimbabwean spirit is unrivalled—absolutely, maddeningly unrivalled—when it comes to kindness and patience and dignity. What more can you expect when your primary school curricula includes formal lessons in generosity and etiquette?

Someone once asked me what excuse Zimbabweans had to be any different. With more (fertile) land than they knew what to do with, an abundance of natural resources and a regional powerhouse economy that defied the very African trajectory of post-independence ruin, what reason did Zimbabweans have to not be peaceful and grateful? The answer is in the future, Mr President. The future that went on to show us that the dignity of the Zimbabwean spirit will persevere in repression and deprivation just as it did in growth and stability. But I think you knew that already. You would not have taken your liberations with them if it were otherwise.

The liberations that began with populist rhetoric seemed at the time harmless to my pre-teen political awareness. At the two decade mark of independence, you called for a redistribution of wealth from the remnants of a colonial minority who continued to own 80 percent of your factors of production. Could I fault you for this then? Can I fault you even now? Where else would a former regime exert full economic control 20 years after independence? You had me on your side until this point, Mr President.

But then commenced the farm invasions. For a man so known for deliberation and careful consideration, did you honestly think this was the way to do it? To reverse the order between ownership of resources and capacity building to manage those resources? Did you think, Mr President, that your economy, or any economy, could survive international isolation? Of all the things you pre-empted, how are we to believe you did not pre-empt absolute destabilisation? My family left at the very onset of Zimbabwe's collapse, but not early enough to have been spared the overnight queues for petrol when you could no longer import oil. Not early enough for hyperinflation to rear its ugly head.

What I know of the decade that followed, I try my best to deny. People carrying wheelbarrows full of your defunct currency to empty supermarkets to buy a loaf of bread, only to have the price change by the time they reach the front of the line so they resort to bartering their shoes to make up the difference. Entire neighbourhoods of Harare going for weeks without electricity or water. Weeks, Mr President, weeks. Weeks when children chased the dying light of the sun to read the novels that your education system so strongly encouraged them to borrow from your beautiful libraries. Weeks when people resorted to digging holes in their backyards to relieve themselves after dark, because where was the water to flush their toilets Mr President?

You have presided over shrinking life expectancy, now one of the lowest in the world, abject poverty, now one of the highest in the world and a deprioritisation of literacy. But you have presided. Presided still. And where has that taken the Zimbabwean spirit? Hustling to put food on the table; telling lies and selling lives.

And what of your regime, Mr President? Was it the global persona non grata that allowed you to assume full authoritarian control of your constituents? To be accountable to no one for human rights abuse and zero tolerance for freedom of expression? Was it easier to unleash campaigns of violent oppression on your opponents and bleed Zimbabwe dry for personal gain because you were a political pariah? Or was it because you felt you had been wronged by the international community?

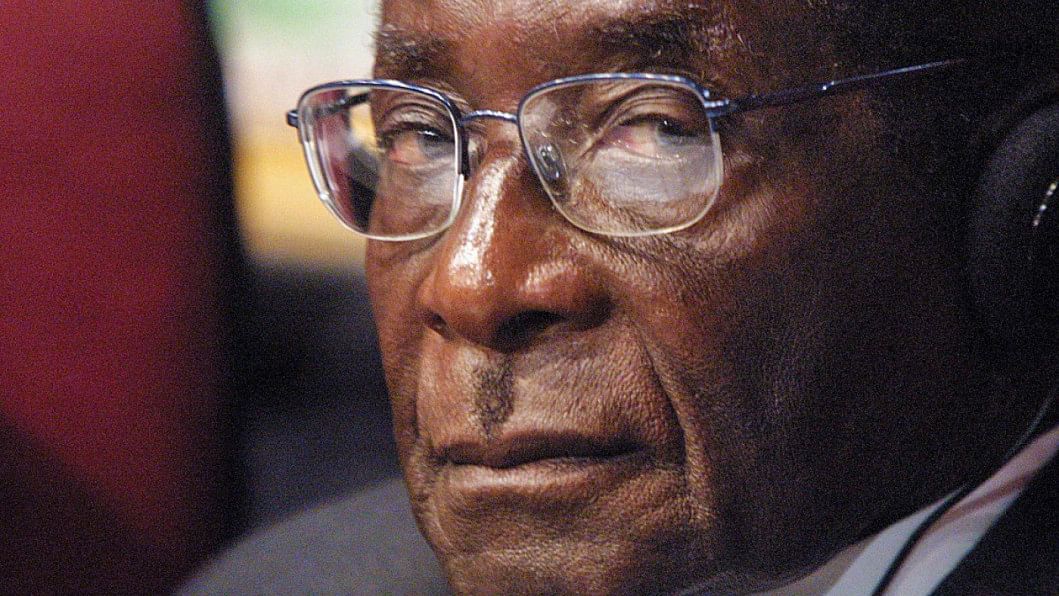

I may not ever know what your reasons were, but I do know that you used to be a great leader. Until you no longer were. And as I waited for your resignation that evening in Bangkok, I am almost ashamed to say I could not bear to see you grovel. To see you so reduced. I did not share the jubilation of your people Mr President, because I did not suffer on your account. But I did get a sense of what they must have been feeling: for a man who had subjected them to such indignity, only an undignified ousting was fitting.

Subhi Shama is a Bangladeshi-Zimbabwean. For all intents and purposes.

Comments