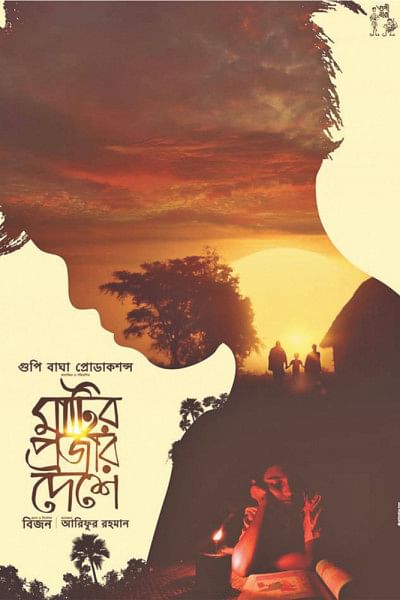

Matir Projar Deshe

Matir Projar Deshe (English title: Kingdom of Clay Subjects), the debut feature by Bijon Imtiaz, has been on the radar of the serious Bangladeshi cinephile for a couple of years now, as news popped up sporadically of the film going to one film festival or another. After winning Best Film at Chicago South Asian Film Festival (ahead of heavyweights like Hansal Mehta's Aligarh and double-winner at Cannes Masaan), the film was scheduled to have its Bangladesh premiere at last year's Dhaka International Film Festival but the producers withdrew it because they were not happy with the screening facilities. It took over a year since then for the film to have a theatrical release, when it made its bow on March 23 at only three theatres (Star Cineplex and Blockbuster Cinema in Dhaka and Upohar in Rajshahi) because the producers could not attract a distributor and had to distribute it themselves.

The film, at its core, is a study of rural Bangladeshi society done through the eyes of a 10-year-old son of a single mother. Without giving away any spoilers (because it is a film that deserves to be seen in theatres), it provides a vivid, almost visceral portrayal of issues like child marriage and dowry, as well as social class dynamics in villages and conservative stigmas. Matir Projar Deshe achieves one of the most difficult things for a film: to be hard-hitting while also being just as tender and sensitive. At the same time, it remains a story through its 88-minute runtime, instead of becoming a preachy PSA serving the so-called 'social responsibilities of film'.

Bijon's camera follows Jamal (played by Mahmudur Rahman Anindo), a carefree pre-teen boy who discovers himself and the world around him—the societal system and its harsh realities, relationships and their meanings, and his own identity—as he takes the journey towards his teenage years. For any debuting filmmaker it is a gutsy move to have your story hinge on a 10-year old, but Bijon does this with assurance and Anindo—with his intensity, vulnerability and innocence all measured up to perfection—acts with maturity far beyond his years.

The other major child artiste, Sheuli Akhter (who plays Jamal's friend Lokkhi), is also commendable in her role, as are the few other children who appear. The main cast is formidable, with Jayanta Chattopadhyay, Rokeya Prachy, Kachi Khondoker, Chinmoyee Gupta and Shakeel Ahmed (who is credited as Monir Ahmed) all doing full justice to their characters despite some of their screen times being rather brief. Gupta in particular—who plays Jamal's mother Fatima and has longer screen time than many others—is a revelation, especially because you expect the likes of Chattopadhyay and Prachy to be fantastic anyway. At the same time, the film is honest in its conscious avoidance of resorting to easy character tropes (most notably with the character of Razzak Hujur), something that keeps the story unpredictable and fresh.

Aesthetically, the film is gorgeous. Cinematographers Andrew Wesman and Ramshreyas Rao capture the idylls of the countryside without overdoing it; their use of light and shadow is magnetic and the interspersing of some allegorical visuals hit home. The film also recorded all audio on-location, a tough challenge to undertake and do well, adding to the authenticity of the story and helping the actors with their characters.

One of the best things the film achieves (and I am convinced it is a very conscious decision executed carefully) is its timelessness. There are no indicators anywhere to show whether the film is set in the '70s or late 2000s, and it makes the story all the more compelling.

There are, however, things that I didn't love about it, albeit those were far outweighed by the positives. Some of the dialogues in the film feel a wee bit too scripted and manufactured rather than conversational (especially in the early part), and there is a parallel I cannot help but draw: that of Amit Ashraf's 2013 thriller Udhao. Both Amit and Bijon studied filmmaking in USA (Amit studied at NYU), and both their films' dialogues feel a bit artificial, at least in places. Maybe it has to do something with detachment, maybe it is just a linguistic barrier—I don't know.

The background score, while appropriate in its composition, sometimes also tends to become a little too 'foreground', almost as if to provide auditory cues to what the scene is supposed to make you feel. Screenplay-wise, a couple of points feel a little rushed—like Jamal's visit to Lokkhi, or the encounter between Fatima and the school clerk. The clerk, whose character serves more as a plot device than anything else, also could have done with a clearer character motivation, as could that of Razzak Hujur near the end. To finish, the colour grading in some sequences (for instance flares, tints, Instagram-like filters) are a little too experimental for my personal taste.

These are not complaints, though—more a wish that these issues were not there in an otherwise near-perfect exercise in cinema.

Matir Projar Deshe was five years in the making, and the care and love with which it was made shows in almost every frame. The film had a start-stop journey due to finances, the main character's father passing away during the shoot, the film having to be pulled out of a festival at home, etc.—but these are all testament to the fact that this is a passion project for Bijon and producer Arifur Rahman of Goopy Bagha Productions. And as brilliant as the film is itself, it is that passion that is the brightest beacon for Bangladeshi cinema. It was good to see the cinephile community on social media (particularly the Facebook group 'Cinemakhor der Adda') putting all its backing behind the film to urge people to go see it. That, and the half-full audience that watched the film at a 10:50 am screening on a holiday, gives me faith. Maybe there is hope for independent Bangladeshi cinema after all.

Fahmim Ferdous is a subeditor, The Daily Star.

Comments