A priceless gem in Copenhagen

On a short trip to Copenhagen, my wife and I, having just visited the Little Mermaid and the Hans Christian Andersen museum, are wandering where to go next. Just then, by a sheer stroke of luck, someone at the tourist information centre casually mentions The David Collection, a museum that specialises in Islamic decorative art. We are instantly hooked. A short walk from the National Art Gallery, we reach a neo-classical building housing the Davids Samling, as it is called in Danish. We walk in, along with a group of school children.

There is no entry fee, a pleasant surprise. Upon a deposit of DKK 10, we get a tablet with a special button on the back, which if tapped against a similar one next to any display, activates the relevant description in English. We head straight to the Islamic Art section that occupies the top two floors. We step out of the lift, and are instantly transported into the realm of Islam: the mesmerising “Orient” with its fragrances, colours, mannerisms, wisdom, artisans, warriors, sages, polymaths, travellers, painters, courtyards, and arabesque designs. It’s a panorama of Islamic civilisation across its length and breadth, from Spain to India also detailing its interactions with other civilisations.

Mind blowing. Rich. Dizzying.

The museum is organised in 20 sections—from The Prophet Mohammad to mid-19th-century India, covering almost every chapter of the Islamic world in between, including the Samanids, Il-Khanids and Golden Horde, Mamluks, Seljuks of Rum and Ottomans. Each is presented in its historical context, with texts, maps, art, coin, architecture, textiles, books and tools, supplemented by three special collections—miniature painting, calligraphy, and textiles. A resource area presents a number of subjects outside their chronological and geographical contexts: 14 cultural history themes; the phenomenon of revivals, forgeries and restoration; and artistic techniques. The cultural history themes include varied subjects, such as: Symbolism in Islamic Art; Trade, Measures and Weights; Mechanics, Astronomy and Astrology; Medical Science; and Art of War.

The sheer number of exhibits is worth noting, way too large to be accommodated in the two floors allocated to the collection. Many items are on display with glass covers, many more are inside drawers for the visitor to pull out and view. It is not possible to describe the whole museum in this short piece and I will only try to give an overview, along with some relevant historical facts.

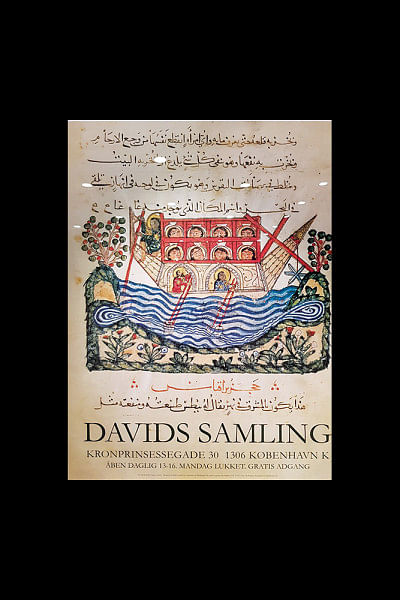

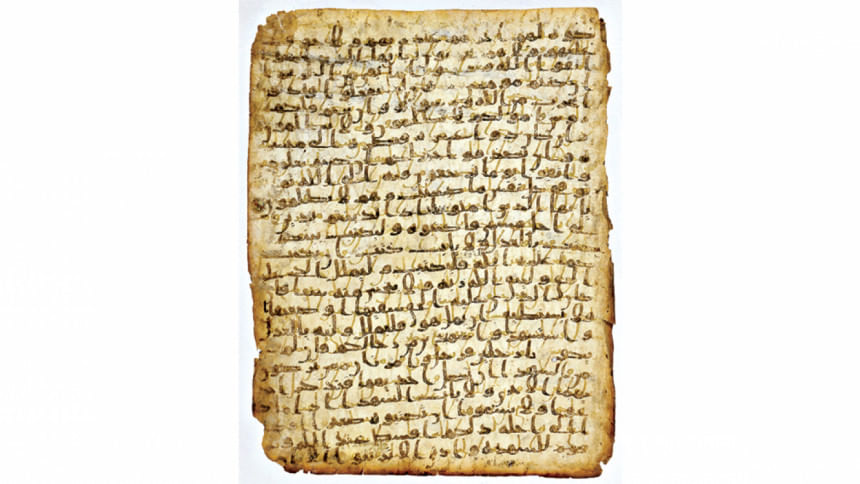

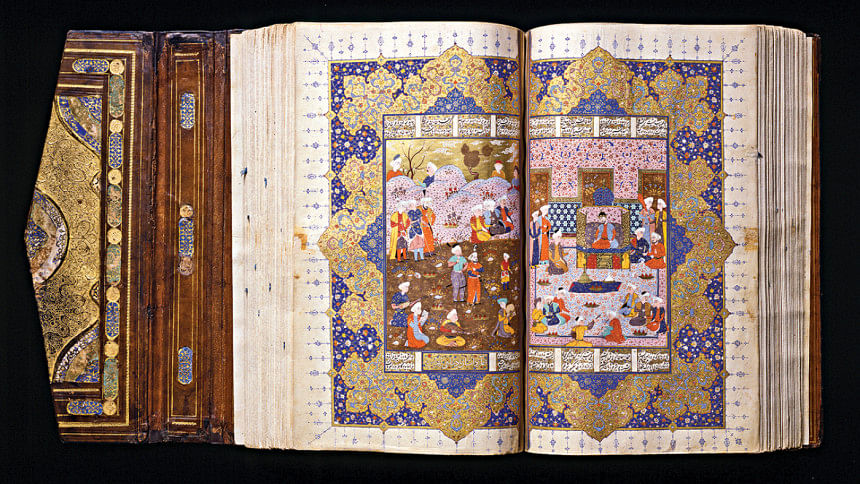

This stunning collection starts with the origins of Islam at Mecca. We are then led to parchment leaves of the handwritten Quran in different calligraphic styles—Hijazi from the second half of 7th century, Kufi from circa 900 North Africa, Maghribi from 14th century Spain or Morocco and so on. The Hijazi Quran, written down shortly after the Prophet’s death, is one of the oldest that has been preserved. Calligraphy adorned with miniature paintings were at the core of Islamic art since the beginning. Later, miniature paintings became independent works of art.

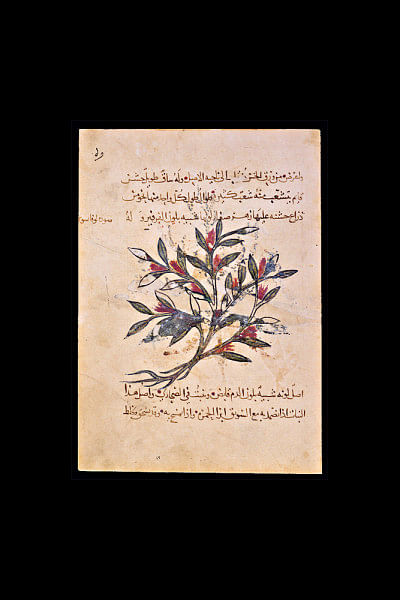

One such miniature work on display is the Arabic translation of Dioscorides De Materia Medica from 13th century Baghdad. Arab pharmacology borrowed significantly from the Greeks and this book is a testament to the importance it gained in the Islamic world. It is a product of the House of Wisdom, a grand library in Baghdad, founded in the 8th century, which undertook large scale translation of Greek and Syriac works to Arabic. Such translation movements led to some of the seminal breakthroughs in science, astronomy and medicine.

Another gallery is displaying the Constellation Gemini in an illustrated copy of al-Sufi’s Kitab suwar al-Kawakib (The Book of Fixed Stars) from 17th- century Iran. Astronomy was important in the Islamic world to determine the times of prayers and the direction of the Qibla, as well as for navigation. From 9th century onwards, data from antique writings were compared with observations made in the Islamic world and the results were compiled in new treatises. It was the Syrian Arab astronomer Al-Shatir (1304-1375) who developed the first accurate lunar model that matched physical observations of its distance from the Earth. Copernicus (1473-1543) proposed his lunar and Mercury models, both identical to those of al-Shatir’s, almost a century later. However, it is not known if Copernicus was familiar with the works of Al-Shatir.

The gallery on textiles is showing intricate designs on oriental rugs, robes and royal dresses, woven in different techniques with wool, linen, silk, cotton and Muslins, dyed with vegetable and minerals. “Art of War” gives an overview of how Islam transformed the squabbling Arab tribes into the most formidable military might in the world that fought relentlessly to spread their belief at a lightning speed, bringing decisive victories from Spain to India and beyond.

Islamic medicine was once the most advanced in the world, combining ancient Greek, Roman, Persian and Indian medicines. It was in 8th century Baghdad that the world’s first modern hospital was founded and the concept of public health service introduced. Muslim artisans invented new techniques and improvised existing ones in pottery, glassmaking, metal, stone and stucco, wood, ivory and leather.

As we walk through the galleries, we bump into the same school group we have met earlier, sitting on the floor around their teacher, listening to him attentively. The teacher doesn’t forget to apologise to us for the “inconvenience” they are causing. We only smile and move on.

The David Collection was founded by Christian Ludvig David (1878-1960), a famous lawyer in Copenhagen. David started in 1910 with a few Danish paintings and sculptures. He soon developed a special interest in porcelain from the Islamic world, which laid the foundation of the most important part of his collection, The Islamic Art, which has now come to be the museum’s raison d’être in a Scandinavian context. David’s Islamic Art is not a large collection when compared with similar others around the world. However, this is perhaps the only of its kind in Northern Europe that tells a story, connects the dots and gives a bigger picture of Islam and its place in history.

The museum repeatedly makes the point that Islamic civilisation contributed significantly to the advancement of science, technology, governance and philosophy. And that it acted as a bridge between Greek and Roman civilisations and European Renaissance. The deep respect and humility shown to Islamic traditions is unmissable. Such museums help us realise that in this world no nation, or for that matter civilisation, can grow alone, and everyone is indebted to others for what they are today. They facilitate reconciliation among nations, and challenge the current trend of post-truth politics. A must-see in Denmark.

Dr Sayeed Ahmed is a consulting engineer by profession, writer, and traveler by passion. He is interested in history, culture, education, and people.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments