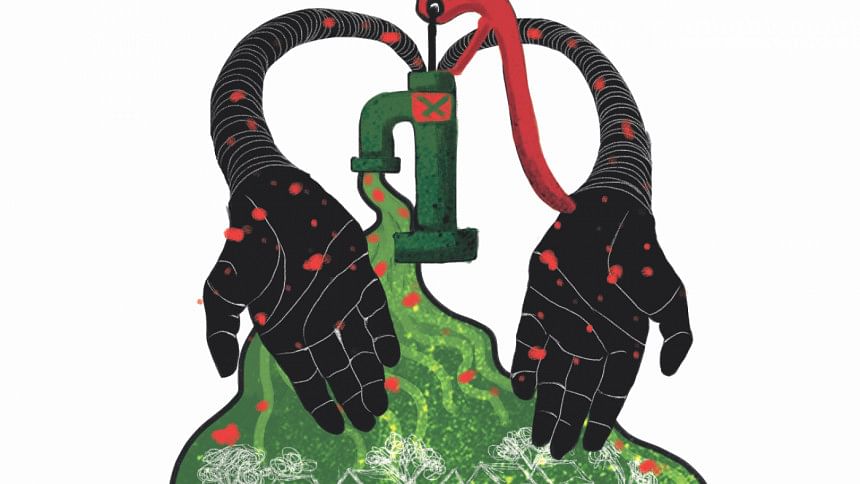

Slow poison

While Dhaka residents continue their ongoing protest against the poor-quality water that is piped into our homes by WASA, at least it is not slow poison. The same cannot be said for millions of villagers in Bangladesh who depend on water from tubewells.

The history of providing safe water in rural Bangladesh is fraught with contradictions. First, in the 1970s, people were told to start using shallow hand-pumped tubewells that the government and NGOs dug. With the tubewells, they would be less vulnerable to water-borne diseases such as cholera and other diarrhoeal diseases from the water they got from nearby ponds. People soon began digging their own wells. It was heralded as an efficient and cheap source of “clean” water.

Then, in the early 1990s, the extent of naturally occurring arsenic in Bangladesh’s groundwater was discovered and its exposure to millions over the decades realised. The World Health Organisation (WHO) called it “the largest mass poisoning of a population in history.”

Arsenic levels in well water in many parts of Bangladesh were found to exceed both government (50 micrograms per litre) and WHO (10 micrograms per litre) limits upon large-scale testing. Beginning 20 years ago now, the government and donor agencies began a massive campaign in rural areas to stop people from digging and drinking from shallow tubewells. A World Bank-funded government effort, it tested five million shallow tubewells in ‘contaminated’ regions and their taps were painted red and green based on whether or not they were contaminated (according to national standards). This, in turn, was cited as a highly successful public health campaign in the country.

But around 20 million people still drink tubewell water with levels of arsenic above the national standard. The number is significantly higher if the WHO recommended standard is applied,” says Dr Kazi Matin Ahmed, chairman of the department of geology at the University of Dhaka and researcher in groundwater.

A recent study showed that while people are still getting affected by arsenic-laden water, interventions to tackle the problem have also had adverse impacts on childhood mortality.

A paper by the U.S.-based National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) published last month said that government/aid campaigns urging people to stop drawing water from shallow wells beside their homes to deep tubewells (farther away) essentially led to more children dying. Villagers went to the well less, storing water for longer which led to it being contaminated with faecal matter and other waterborne diseases.

The team behind the research collected data on water use and mortality between 2007 and 2009 from households in Barisal encouraged to switch water sources, as well as those that were not. Those that switched away from arsenic-contaminated wells post-1998 to wells that were farther away, had 46 percent higher child mortality rates than households with arsenic-free wells. It was not just children getting affected—those households had increased adult mortality as well. Pre-1999 (before the campaign urging households to switch), “mortality rates were almost identical in contaminated versus uncontaminated households,” states the report.

The NBER study concludes with the emphasis that while well-meaning, such a public measure urged people to change their established drinking habits and stop using existing wells without providing bacteria-free water sources nearby—which ultimately had fatal results.

This was essentially a double blow for this population—a 13-year observation by ICDDR,B of people chronically exposed to arsenic found that the heavy metal compromises immunity. The study found that young adults were five times more likely to die from different diseases at an early age when exposed to an average of 223.1 micrograms arsenic per litre of water. When aid interventions encouraged communities to switch to fetching water from the far-away deep tubewells, and storing it for longer, it introduced pathogens to a population whose immunity was already dampened.

There has been no concerted response to rectify the fatal mistake from public health and development practitioners and policymakers. Introducing villagers to drinking water laced with high levels of arsenic is not marked as a failed aid intervention in the country, which is largely presented as a universal development success story with one of the fastest growing economies and outperforming its (richer) South Asian neighbours in human development indicators.

In the meantime, funds have been diverted to more “pressing” concerns in the aid world, say experts in the field. Measures to reduce arsenic exposure, namely arsenic awareness programmes and testing of new wells, are not being taken on a significant level anymore, they say.

Villagers with no safe tubewells nearby have been left to take their own measures—either digging deep tubewells themselves (which can cost between Tk 70,000 and Tk 1 lakh and so, is out of reach for most villagers) or use a crudely-devised filtration system involving multiple stacked kolshis.

“It is no longer seen as a priority. Where it was once the number one priority, it is now off the priorities list,” says Dr Mahfuzar Rahman, epidemiologist and formerly at ICDDR,B and BRAC. “There are no large-scale arsenic education campaigns and well testing anymore,” says Dr Rahman, because there is no funding for it.

In 2016, a Human Rights Watch report stating that an estimated 43,000 die each year from illnesses as a result of arsenic exposure, was labelled by a leading government official as “false” and “politically biased”. The report (and other media reports) also notes that politicians allocated government water points in areas giving priority to their political supporters and allies. It found government tubewells located inside private households with political connections and other places where access was restricted to the rest of the villagers.

The government currently has a three-year Tk 1,990.95 crore arsenic mitigation programme to run through 2021. Only in 2009 (more than 10 years after the original well testing) did the Department of Public Health Engineering (DPHE) and the development organisation Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) complete a situation analysis report which pinpointed areas where over 60 percent of tubewells were arsenic-contaminated.

Accordingly, alternatives called “safe water devices” (ranging from pond sand filters and rainwater harvesting to arsenic-iron removal plants) are being provided in these areas. But safe deep tubewells are by far the most common alternative provided.

“We test water quality immediately after constructing deep tubewells, for four parameters including arsenic,” says Al-Amin, executive engineer in charge of the arsenic risk reduction project at DPHE. While this is only for government tubewells, he points to arsenic screening programmes which test private tubewells too—in 54 districts, 335 upazilas, and 3,200 unions under this project undertaken by the government.

Dr Matin, who co-authored a paper published last month analysing the effectiveness of arsenic mitigation approaches over 18 years in Araihazar (an upazila in Narayanganj) and its implications for national policy, says while government resources are being allocated, it is not reaching many people who still have no alternative to drinking arsenic-laced water. He also says better technology and more cost-efficient options need to be considered, and fast.

“Deep tubewells have been pushed as the best option available [for drinking water needs], but there are other options which need to be looked into. Intermediate aquifers, instead of deep aquifers for example, would be a cheaper option and so, be able to provide greater coverage of areas and people with arsenic-free water,” he says.

The paper, published in Environmental Science and Technology, recommends that a survey of wells be done again in order to identify low-arsenic wells which can be shared by households (the cheapest option at an estimated cost of less than USD 1 per person for reduced exposure) and new wells tapping intermediate aquifers (low in arsenic) be installed (at USD 30 per person), in contrast with the preferred solution of installing deep tubewells and a piped-water supply system by the government at an estimated cost of USD 150 per person.

Dr Rahman agrees that a blanket survey of tubewells across the country is needed. He points out the red/green-painted tubewells have long since faded with no effort made to distinguish unsafe wells from safe ones. “The government needs to do something permanent to reduce arsenic exposure. Policymakers can no longer neglect the issue.”

The failed aid intervention to provide clean water and ultimately leading to arsenic poisoning in rural Bangladesh is the subject of the 2015 book The Inheritance Powder by Hilary Standing, a social anthropologist specialising in health who has worked in India and Bangladesh. The author writes in a December 2016 article in the South China Morning Post, “Where does responsibility lie? What agents should be held to account? How far are these failures of politicians and governments, of international agencies, of legal processes? And do the roots lie deeper, in models of development driven by Western consultants?”

These lead to questions of our own. 20 years since arsenic was identified as a major public health risk, why are 20 million people still drinking arsenic-contaminated water above safe standards in the country? Why have there been no concerted efforts made by the international development world and national agencies to fix and compensate for a disastrous aid intervention which resulted due to negligence and insufficient precautions?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments