Beyond the book—this is how the youth read

Those of us who love literature are haunted by an ever-looming threat: that reading as a practice around the world is dwindling. In some ways, the threat is potent and evident—if public libraries around the world are starving from lack of funding, the very idea of visiting libraries to read for leisure is a rarity here in Bangladesh, given their shabby states. Inundated by self-published content, often of poor quality, the Bangladeshi publishing industry pines for good editors, publicists, and standardised laws and regulations, as do authors. Theirs is a tricky dilemma: to survive or to create? Bookstores, meanwhile, struggle to attract and retain clients.

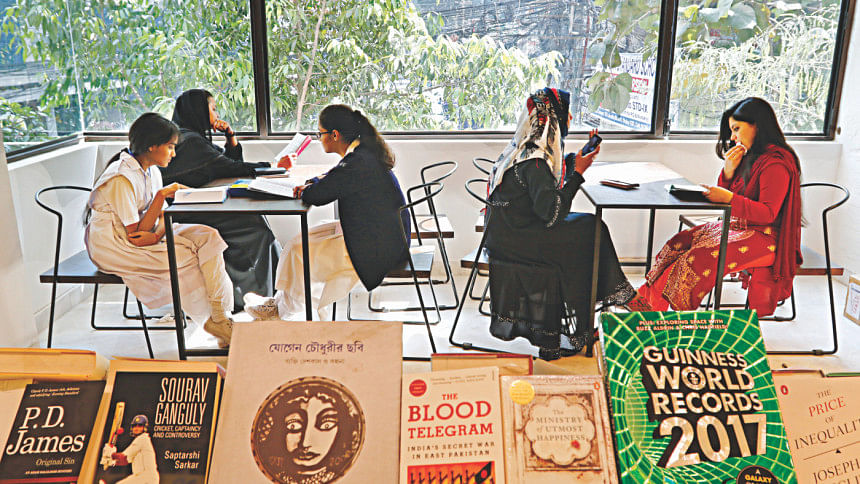

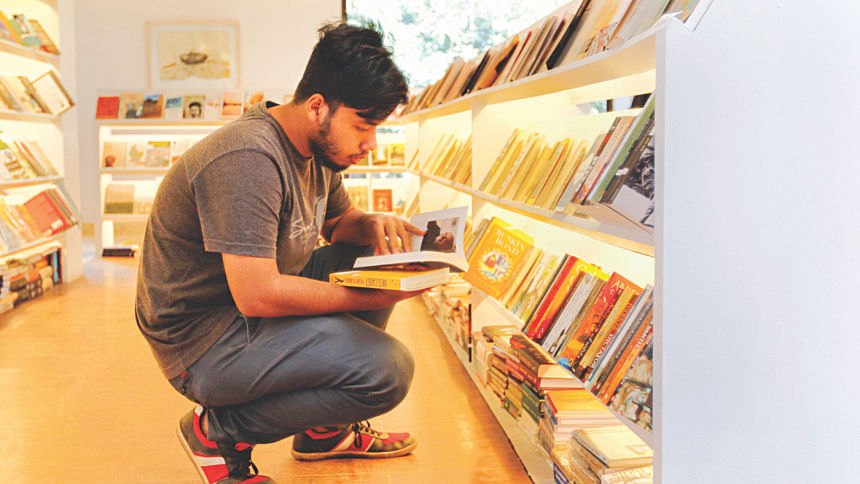

This article, however, is a happy story. Happy because even in the face of these obstacles, the world of books both globally and in Bangladesh has managed to turn malleable. Some of its victories have been traditional—despite the very real fear that physical books are dying, as Vox pointed out in 2018, brick-and-mortar bookstores have become a popular avenue of escape as we spend more and more of our time online. In a modest survey carried out by The Daily Star for this story last month, roughly 83 percent of the 34 respondents shared that they prefer to read print books compared to other media. 74 percent of them read more than 10 books each year, and only 11 percent read less than five.

Yet, the more exciting spectacle occurs in the digital arteries of our lives, where books have managed to sneak in and stake claim in the form of audiobooks, podcasts, adaptations, digital art inspired by literature, bookstagramming, social media communities, and consequently endless, endless conversations surrounding literature. Dwell on these practices awhile, and one realises that while the young reading community in Bangladesh might be modest in size, its strength lies in its shifting shape, in the fun and creative ways in which it is engaging with books in addition to simply reading them.

"Book blogging and reviewing always makes me read more," says Zebun Nesa Bristy, a member of the Facebook community Litmosphere, which is 7.1k members rich. Since starting in August 2016, Litmosphere has grown beyond just a platform for book recommendations. On any given day, Litmosphere's Facebook page and associated Facebook group buzz with reviews, reading challenges, writing prompts (the wildly popular Sehri Tales challenge during Ramadan), physical and virtual book exchanges, and friendships forged over overlapping and clashing opinions on literature. The same, albeit on a quieter scale, is evident in the Facebook pages of Book Club Bangladesh (which boasts 1.7k members) and other such groups.

"It's like we grow in books together and when I read, I [am] not alone, those other people are always with me without actually disturbing or interrupting the process," Bristy explains.

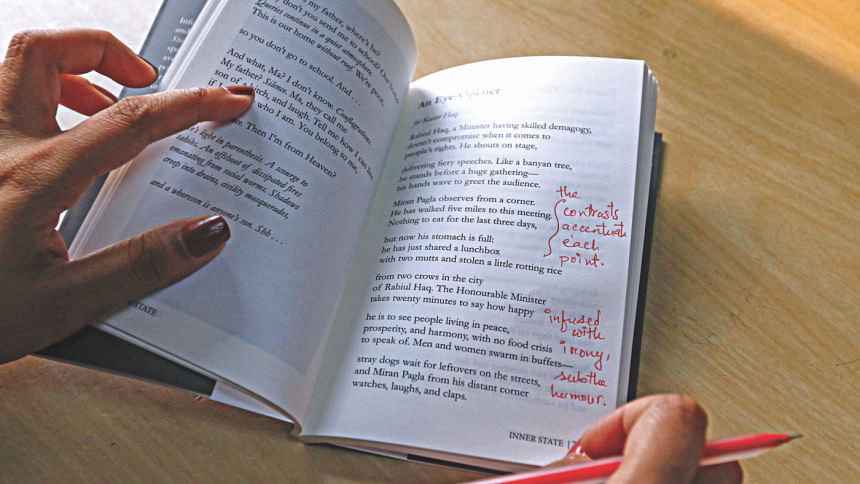

These exchanges alter both individual and collective reading experiences. Conducting the survey for this story revealed booktubers, aspiring novelists, book club moderators, and readers who collect and curate quotes. 62 percent of the respondents—all devout readers, all aged between their teens and 20s—write book reviews; 38 percent engage in book clubs, 35 percent run book blogs, and 47 percent annotate while reading so they can share their thoughts with others. The result is a flurry of recommendations and ideas across each individual medium, some visual, others textual, but all uniquely interactive.

Annotating, for instance, builds a tactile relationship between the reader and the text—enhancing that reader's critical capacity in the process—and leaves behind a fascinating trail of her interaction with the book, of the flavour of her own thoughts, on its margins. When that same book changes hands because someone else from the online community perhaps asked to borrow it, the marginalia find a new pair of eyes. Bristy, who blogs as @bibliophilic_litterateur on Instagram, initiated a trend of writing 'book letters' based on the same premise, whereby readers annotate on books specifically to communicate with future readers. The book changes hands. New marginalia are etched. Fresh meanings are exchanged. Personalities are discovered, both of the reader and the text. And the book bears physical witness to it all.

Meanwhile, the practice of reviewing brings forth something radical.

Published book reviews in the traditional sense have always contained an implicit hierarchy. This is me dictating your tastes, informing you of what you should and shouldn't read, because my training and expertise make me an authority on the subject—the reviewer seems to say to the reader. This power dynamic may be invisible, but it certainly operates in Bangladesh. In several past interviews, publishers and booksellers in Dhaka have told me candidly that their book sales suffer because the media doesn't review most books, and so readers are simply unaware of them. This discourages distributors from bringing in many interesting titles from abroad, which swivels back to deprive Bangladeshi readers of a quality offering of books.

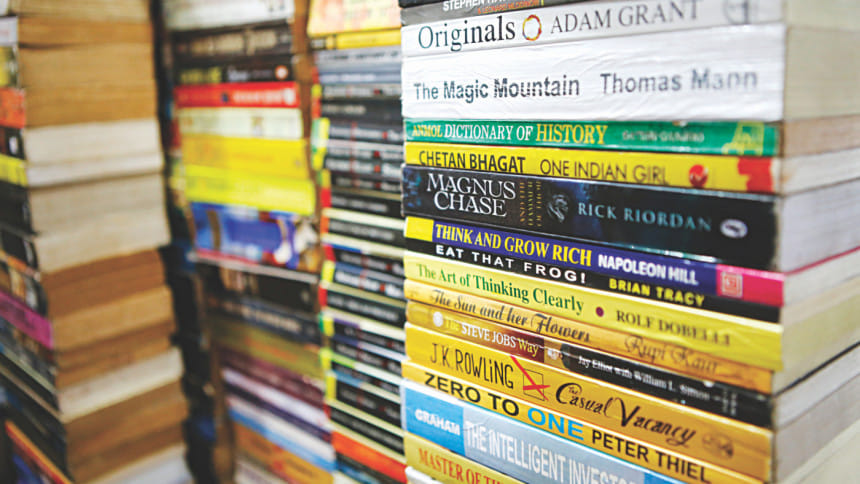

Digital media makes these barriers just a tiny bit more porous. While platforms like Goodreads and other international media bring interesting literature from abroad to our attention, the volume of unofficial, unpublished reviews posted on online book communities democratises the very practice of book reviewing. Attention to books no longer depends on the hallowed expertise of a few; it flows through a plethora of tastes, backgrounds, and writing styles—the latter, in this case, sometimes being more accessible than published reviews. The reviewing culture also cultivates critical thinking among a layman audience without requiring formal education in literature; it inspires readers to start writing, develop their own style, and widen their reading horizons.

Of course, the risk of orbiting back to the same old genres remains— "I find most book suggestions in [online] groups to be very basic and unnecessary. There are so many important novels to read [beyond] Harry Potter and Colleen Hoover. Many people here know nothing beyond the boundaries set by fiction from the West. That needs to change," Shah Tazrian Ashrafi, avid reader and a freshman of Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP), points out.

The popularity of literary festivals tackles this problem. Every February, the Amar Ekushey Boi Mela offers an ultimate reminder of the sheer size of the book reading audience in Bangladesh. The stretch of land spanning the Suhrawardy Uddyan and the Bangla Academy premises jostles with mammoth crowds; the fair brought in Tk 70.5 crore in book sales in 2018. Come November, a fraction

of the same audience—this one with a bend for literature in English—throngs the Bangla Academy premises again for the Dhaka Lit Fest. The event engages countless youths not only in the purchase of books, but also in hosting sessions, planning activities for stalls, attending to local and international literary giants, and partaking in discussion of ideas as audience at the DLF panels.

"We have at least 200 [youth] volunteers every year, but more applicants, a few thousand," the DLF team tells me. "About 30,000 under the age of 25 registered [to attend the event] in 2019. This number has been growing every year."

Aliza Rahman, a North South University student who attends DLF regularly, shares, "I love the new releases and publishers I wouldn't have known [about] otherwise. Last year I was fascinated [to know] that they were releasing a comic book on Bangabandhu. As a child, I would've enjoyed reading about dry topics such as history more, had they come in comic book form. But what I like most [about the event] is getting to hear authors talk and discuss issues."

Tazrian adds, "I get to be a part of something bold, defiant, and necessary—which is the celebration of literature in the face of constant blows on free speech."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments