Bangladesh began badly: Remembering the roots of the impasse

Nationalism is not a political doctrine, not a programme. If you truly want your country to avoid regressing, halting, failing, it is necessary to march past national consciousness to political and social consciousness.

–Frantz Fanon, Les damnés de la terre, p. 192

"A conversation is invariably shaped," says Stephen Holmes, professor of political science, "by what its participants decide not to say. To avoid destructive conflicts, we suppress controversial themes. In Cambridge, Massachusetts old friends shun the subject of Israel in order to keep old friendships intact." "Burying a divisive issue, of course, can be viewed censoriously—as evasiveness rather than diplomacy," he agreed (Holmes 1993:19). In Bangladesh, the normal political discourse in general prefers to keep quiet on the origins of the present impasse. I believe at some point we need to reconsider the gag rules. The following notes are but an attempt at negotiating the gag rules.

I

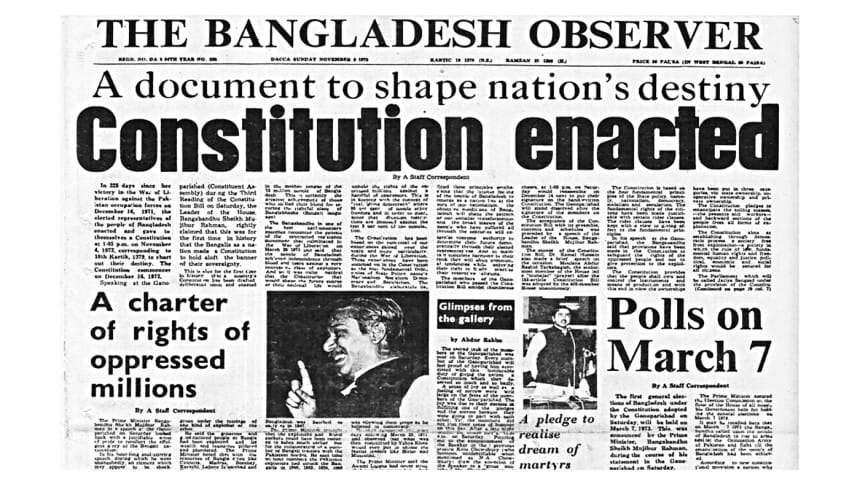

The course of events after March 25, 1971, including a campaign of genocide by the Pakistan armed forces, led to the independence of Bangladesh as "a sovereign People's Republic". The raison d'être of the de jure declaration of independence, on April 10, 1971, included the words, "in order to ensure for the people of Bangladesh equality, human dignity and social justice" (Hasan 2019:222).

An eight and a half-month-long war of resistance, topped off by a brief frontal combat in December, ensured the independence of Bangladesh, de facto, as a new nation state in a cold war world. "Seldom has a nation started its independent life under circumstances as inauspicious as Bangladesh," remarked John Owen, an American observer, in 1972 (Owen 1972: 209). Rounaq Jahan, of Dhaka University, also noted: "A poor, over-crowded land, its economy ruined by a nine-month-long Pakistani military occupation and a national liberation war, Bangladesh was looked upon by many as an 'international basket case'" (Jahan 1973: 199).

"The Awami League regime had a shaky start," this dictum of Rounaq Jahan's was only a half-truth. She was only shy of telling the real tale: it was indeed a false start. The government in exile hardly had a grip on the ground. It was utterly dependent on the Indian armed forces for its writs. "After the liberation of Dacca on December 16, 1971," as Rounaq Jahan writes, "it took the Awami League government in exile five days to come to Dacca and establish a government. In the first two weeks it did little except to pray for the release of its leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman from prison in Pakistan. Its call for the surrender of arms went largely unheeded and the task of providing protection to the ('nearly half a million non-Bengalis who were looked upon by Bengalis as collaborators and traitors') was entrusted to the Indian army" (Jahan 1973: 201).

On being released from a nine-month-long solitary confinement, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman returned to Bangladesh on January 10. In a public speech on that day, in Dhaka, he laid down the major principles of his regime. He proclaimed that the policies of his regime would be based on the principles of secularism, democracy and socialism. As Rounaq Jahan instantly noted, "in his first public speech (in post-liberation Bangladesh) Mujib mentioned only three of his now famous four principles. Nationalism was missing from the list then and was only later added" (Jahan 1973: 201).

In his airport speech in Dhaka on December 22, Tajuddin Ahmad, prime minister of the regime, had already proclaimed these three principles—socialism, democracy and secularism—to form the foundation of the new state. He reiterated the same scores in his speech at the secretariat the next day (Hasan 2019: 206). Most notably, what was missing in his speeches too was any reference, whatsoever, to the fourth principle of nationalism. It is the burden of this note to claim that roots of our contemporary malaise, not just constitutional ones, are found in this surplus moss of nationalism.

II

Bangladesh, if it so wished, could have learned a lesson or two from the Algerian experience. It was chiefly with the Algerian experience that Frantz Fanon helped himself in formulating his decisive insights on the national middle class. "In a certain number of underdeveloped countries," Fanon wrote, "the parliamentary game is falsified from the bottom up. Powerless economically, unable to put in place coherent social relations, and standing on the principle of its domination as a class, the bourgeoisie chooses the solution that seems to it the easiest, that of the single party. It does not as yet have the honest conscience and this peace of mind that only economic strength and control over the state machinery alone can confer. It does not make a state which reassures the citizen, but one which causes him disquiet" (Fanon 2002: 159).

Fanon encountered the single party as "the modern form of bourgeois dictatorship, unmasked, unpainted, unscrupulous and cynical," and its only leader as a tool for both "stabilizing the regime and perpetuating the domination of the bourgeoisie." He wrote: "The bourgeois dictatorship of underdeveloped countries draws its strength from the existence of a leader. We know that in the well-developed countries the bourgeois dictatorship is the result of the economic power of the bourgeoisie. In the underdeveloped countries on the contrary the leader stands for moral power, in whose shelter the thin and poverty-stricken bourgeoisie of the young nation decides to get rich"(Fanon 2002: 160).

Nationalism of the middle class, as Frantz Fanon said, is a poor substitute for real social and cultural transformation. Bangladesh, not unlike Algeria a decade earlier, too had a false start—Bangladesh est mal partie (Bangladesh began badly), to paraphrase Mohammed Boudiaf (his war time name was Sidi Mohammed), one of the nine historic chiefs who triggered the Algerian Revolution on November 1, 1954 (Ahmad 2006: 95, 100).

The Algerian Revolution has been, in Eqbal Ahmad's words, "a landmark war in modern history which lasted for seven years and a half, caused France's Fourth Republic to fall, brought Charles De Gaulle to power, and gave birth to the Fifth Republic and to independent Algeria. One out of every ten Algerians fell in this war; and three out of ten were displaced." Sidi Mohammed played a central role in the most formative years of the struggle. Taken prisoner by the French along with four other chiefs (Rabah Bitat, Ait Ahmed, Mohammed Khider and Ahmed Ben Bella) on October 22, 1956, Boudiaf spent the next five years and a half in prison until Algeria's independence in the summer of 1962.

Later, Sidi Mohammed was sentenced to death by Ahmed Ben Bella after the liberation of Algeria and he had no way but to end up in exile. Many years later, when serving as president of an Algeria in ferment, he was murdered in shady circumstances, on June 29, 1992, allegedly by Algerians in revolt against their government. Eqbal Ahmad, who knew Sidi Mohammed in person, is not convinced: "It is hard to imagine a more ironic victim of rebellion. It is at least as likely that he was murdered by elements of the corrupt Algerian establishment" (Ahmad 2006: 94).

The Algerian Revolution, ideologically opposed to personalism in politics and explicitly committed to collective leadership, was run all the way from November 1, 1954, the day of launching the war of liberation, to the achievement of independence in July 1962, by the collective leadership of committees. No one became the uncontested leader of the FLN (Front de Libération Nationale) though there were powerful figures in it like Krim Belkacem, "possibly the most brilliant Arab soldier in several centuries," according to Eqbal Ahmad, a man who knows modern history of the Arabs inside out (Ahmad 2006: 96).

Why such an obsession with collective leadership in Algeria? It was rooted in the annals of Algeria's struggle in the late colonial era. Nearly all of the FLN leaders were once members of the People's Party of Algeria, PPA, founded by the legendary figure Messali Hadj, the autocrat who is regarded by historians as the father of the Algerian nation. "The younger men left him," observes Eqbal Ahmad, "because he had become autocratic and would not heed their urging for a call to revolution. The split was stormy and bloody. The FLN had to fight its way not only into French garrisons but also through the well-organised thickets of PPA militancy. In this primordial struggle, their primary weapon against the historic hero was his autocratic personality and their collective one" (Ahmad 2006: 96).

How did Algeria, then, become autocratic and blood-thirsty, since the liberation of the nation? Eqbal Ahmad puts it squarely on the head of Ahmed Ben Bella, a credible hero but not a supreme one, who betrayed the principle of collective leadership and projected himself as the number one leader of the Revolution, and was duly betrayed by Houari Boumedienne, his ally in the ALN, the military organisation of the Revolution. Ben Bella's personality cult met its nemesis there.

Ben Bella, it is well-known, was one of the five Algerian chiefs captured by the French in October 1956. He had some advantages, including his good look, his record as a decorated soldier in the colonial army, and his relations with Egypt's Abdel Nasser. Ever since his capture by the French, both Radio Cairo and the 'Voice of the Arabs' (Sawt al-Arab), began projecting Ben Bella as Algeria's Abdel Nasser. "As the most publicised prisoner of France, he began to symbolise to Algerians their ever-growing community of suffering." Interestingly, the French too helped building his image by portraying him as an Egyptian proxy. "For opposite reasons," remarked Ahmad, "France and Egypt participated in the making of the Ben Bella myth" (Ahmad 2006: 96).

The rest, as they, is history. Algeria barely avoided an open civil war. Ben Bella came to power and held it until 1965, when Colonel Boumedienne thought it fit to dispense with him and put him in prison. Eqbal Ahmad puts the blame for Algeria's false start squarely on the duo: "The major portion for the false start goes to Ahmed Ben Bella and to Houari Boumedienne, his forceful ally and tormentor. They drained the mainsprings of the Algerian Revolution. Ben Bella violated its commitment to collective leadership. Boumedienne ignored the revolution's participatory legacy and imposed upon it a centralised, bureaucratic scheme of industrial development. Algeria's contemporary predicament had its roots in that time" (Ahmad 2006: 95).

III

In Bangladesh, ever since January 11, 1972, empowered by the Proclamation of Independence Order (April 10, 1971), Sheikh Mujibur Rahman issued the Provisional Constitutional Order (P.O. 22) stipulating a unitary republic and parliamentary form of government. As it transpired, the Awami League sought to rule by Mujib's charisma and build a political process by dicta. "The Indian model of political development appears to be his model," observed Rounaq Jahan. "This means," she glossed, "it wants to have a parliamentary democracy with a single dominant party and a relatively free political process with restrictions on the extreme left and the extreme right" (Jahan 1973: 202).

The desire to found the republic with a single dominant party was reflected in the constitution making process. The Bangladesh Constituent Assembly Order, March 23, 1972, provided for the Constituent Assembly comprising the members elected from Bangladesh to the Pakistan National Assembly and the East Pakistan Provincial Assembly in 1970 and 1971. It blithely ignored Maulana Bhashani's plea that the Constitution be framed by a national convention comprising representatives of all political parties and mass-organisations which had participated in the liberation struggle and should be ratified by a referendum (Huq 1973:63).

The Communist Party of Bangladesh did not think that the Constituent Assembly, as constituted, had the sole authority to frame the Constitution and, though they did not have the will to fight another battle for equality, human dignity and social justice, they were unhappy with the gag rule. Their common complaint was that "the ruling party ought to have consulted the 'patriotic' political parties and organisations which actively took part in the liberation war, on such a vital matter as constitution-making; by not doing so it had exhibited a one-party narrow mentality and disregard for public opinion" (Huq 1973: 66).

Rejecting these claims, the Awami League regime claimed legitimacy with reference to the elections held in 1970 and 1971 and their leadership in the liberation struggle. A spokesman claimed legal competence of the regime to continue with reference to the 1970/71 elections in which the people had given the Awami League an unqualified mandate (it had captured 167 out of 169 National Assembly seats from former East Pakistan and 288 seats out of 300 in the Provincial Assembly).

The Awami League, however, conveniently forgot the terms of the mandate. The mandate was offered in a classically republican spirit which understands politics to be a system of widespread public participation in the governmental process, achieving unity for a community of suffering. This understanding stands in contrasts with modern pluralism which sees politics as a struggle among self-interested groups and classes for the social pie. The Awami League, in 1972, "rejected the idea of holding a national convention to consider the Constitution and said that there was no logic in discussing the Constitution with those elements who had been totally rejected by the people in the last elections" (Huq 1973: 66).

One more presidential order provided for vacating the seat of an Assembly Member if the member resigned or was expelled from the political party which nominated him at the election to the Assembly. On a point of fact, according to the Provisional Constitution Order, the number of seats in the Constituent Assembly was 469 (169 members elected to the National Assembly plus 300 elected to the Provincial Assembly). By March 1972, ten members had died (five killed by the Pakistan Army), twenty-three lost their seats by being expelled from Awami League, two disqualified for paying allegiance to Pakistan and four others imprisoned for collaboration with the enemy. Abul Fazal Huq, a contemporary political analyst, rightly noted: "this provision, obviously intended for ensuring party discipline, had its impact on the constitution making process" (Huq 1973: 60).

Article 70 of the proposed constitution was controverted both at the drafting and the enacting stages. It provided that "if a person elected as member of parliament at an election at which he was nominated as a candidate by a political party, either resigns from or is expelled by that party, he shall vacate his seat." Four members of the Committee (all belonging to the ruling party) differed: "it is against all principles of democracy and violative of rights of electors," They feared that it would render the members of parliament subservient to the party leadership and would lead to undesirable rivalry and disruption (Huq 1973: 61-2).

The constitution of Bangladesh is an interesting document, according to Rounaq Jahan, "since it is an attempt to facilitate political development in Bangladesh according to the Indian model." Its suicidal tendencies included a unique dictatorship of the prime minister by means of disciplinary measures and a system of perpetual emergency, ensured by emergency powers guaranteed which can effectively negate all fundamental rights written into the constitution.

The contradictions hidden soon began to bear fruit. The Awami League resolved to rule by all means necessary, by consent if possible, or by force if necessary. It emphasised two weapons: the new youth front and the old hand of patronage. The party in power had access to a vast amount of patronage. ''Through liberal distribution of permits and licences, the Awami League can be expected not only to hold on to its original bourgeoisie (sic) support base but also to expand it further," noted Rounaq Jahan (Jahan 1973: 205). She, of course, forgot to add that this too was an emulation of the License-Permit Raj, the Indian model of political development since Jawaharlal Nehru.

Topping it off, the Awami League resorted to the lender of last resort, its greatest creditor for legitimacy, the sole leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. As Rounaq Jahan reported: "As well as being the father of the nation and the Prime Minister, Sheikh Mujib occasionally and judiciously projects his image as the party leader." He has said enough in his important public speeches on June 7 and December 16 in defence of his Party to popularise a new ideology— "an ideology that again claims legitimacy from the charisma of the leader" (Jahan 1973: 205).

I quoted rather liberally some contemporary sources in order to emphasise the origins of our present malaise in the earliest days of our republic. I will quote Rounaq Jahan for one last instance. She had the courage to write: "This attempt to develop an ideology based on a personality cult [that is, Mujibbad], has hurt Mujib's image. By identifying the new political structure too closely with his personality, Mujib is held responsible for all the deficiencies of the new system. Even the personal failings of the Awami Leaguers are blamed on Mujib and Mujibbad. Additionally, this attempt to build a personality cult is reminiscent of the Ayub era and hence is looked upon by many as a fascist trend" (Jahan 1973: 206; emphasis in the original).

The fascist trend thus set in motion cannot be a credible defender of either liberation or democracy. The democratic option was thus closed to Bangladesh, like it was the case in Algeria, at the moment of its liberation. The nation failed to realise in time that authoritarian rule kills creativity, breeds corruption, and distorts society" (Ahmad 2006: 103). It is painful to see the tragedy. But to understand that Bangladesh began badly is a sine qua non before coming to terms with the bourgeois oligarchy that rules the country to this day.

Salimullah Khan is a Professor at the General Education Department of ULAB.

References

Abul Fazl Huq, 'Constitution-Making in Bangladesh,' Pacific Affairs, vol. 46, no. 1 (Spring 1973).

Eqbal Ahmad, 'Algeria Began Badly: Remembering Sidi Mohammed,' in C. Bengelsdorf and others, eds., The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

Frantz Fanon, Les damnés de la terre (Paris: Découverte, 2002).

John E. Owen, 'The Emergence of Bangladesh,' Current History, vol. 63, no. 375 (November 1972).

Muyeedul Hasan, Muldhara '71, 16th impression (Dhaka: The University Press, 2019).

Stephen Holmes, 'Gag rules or the politics of omission,' in J. Elster and R. Slagstad, eds., Constitutionalism and Democracy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Rounaq Jahan, 'Bangladesh in 1972: Nation Building in a New State,' Asian Survey, vol. 13, no. 2 (February 1973).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments