Constitutional borrowing and transplants

When modern constitutional ideas and concepts had already been well seasoned and developed, the Bangladesh constitution emerged in 1972, in the wake of the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. In order to draft, constitute, and enforce a constitution, work began at the helms of the constituent assembly (CA) to give their people the Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. Seeing as worldwide, the spectrum of constitutional law had been developed quite the bit already, it would therefore be only natural that advertently or inadvertently there would be mention of foreign constitutional concepts since writing a de novo constitution which is dissimilar and void of influence of each and every other constitution at that time would be next to impossible. Analysing the influence during the adoption involves taking ourselves back to the drafting committee of the constitution in the CA. When doing so, we can look at two key facets, explicit mention and reference to a foreign constitution when adopting and or being influenced by a foreign constitution, or through implicit mention where it can be inferred that reference to a foreign constitution has been made. One such example of the latter could be the concept of constitutional supremacy, there is no explicit mention of it being brought up as a distinct borrowing of a foreign constitution or constitutional law, but at that time this concept was part of the pool of already existing constitutional ideas, which we can infer influenced the existence of this concept in our constitution. Moving on towards the influence of world constitutions during the last 50 years, it again involves two distinct facets: constitutional amendments and judicial interpretation through the years. When analysing the judicial interpretation, we can look at landmark cases which portray the extent to which world constitutions have shaped constitutional developments till now. Upon these analyses, we can examine how much benefit, in actuality has been reaped from this constitutional borrowing and what potential benefit is there in implementing constitutional transplantation and usage of comparative constitutional law for our future endeavors in the field of constitution and constitutional law.

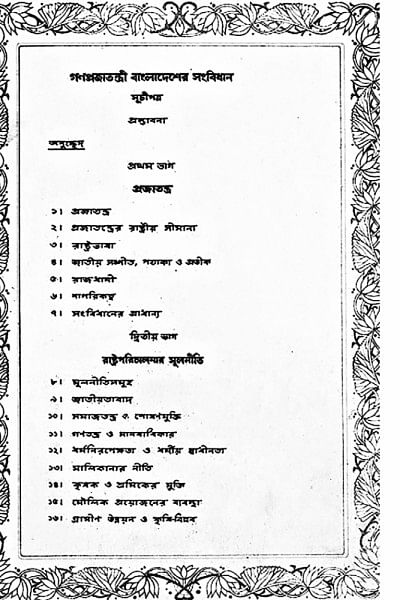

Regarding the use of a preamble at the beginning of a constitution, one of the members of the CA mentioned that it was a common practice and a general constitutional model to have vested in a preamble of the constitution the basic ideals of the state, cited to be evidently seen in the preambles of the constitutions of the United States of America, France, India, Yugoslavia and USSR.

The model of civil and political rights in the constitution of Bangladesh can be attributed to the US model, however not in its entirety. Article 26 clearly reflects the US model, while provisions like Articles 36 to 41 are characteristically more attributable to influences of the Indian and Pakistani constitution owing to their rights-based approach in a positive dimension. During discussion in the CA, several members argued that fundamental rights should be recognised in their absolute form without any restrictions by citing several foreign constitutions. For example, the first amendment of the American constitution was cited as exemplary for freedoms not bound by restrictions, coupled with the argument that there should be an exclusion of the words "subject to reasonable restrictions" from the enunciation of our fundamental rights. The existence of restriction on the freedom of association in the Pakistani constitution was argued to be substantial deterrence to including it in the constitution of Bangladesh. Concomitantly, removing restrictions on freedom of expression was argued, citing the constitutions of Japan, Afghanistan and the USSR. Consequently, all of these arguments fell into quite the array of disrepair, as they were rejected by the majority of the CA. Substantial counterarguments included the statement that fundamental rights cannot be absolute and must be subject to restrictions, citing that such was the same in all democratic and socialist constitutions of the time, and that despite there being no mention of restrictions in the ten amendments containing the Bill of Rights in the US Constitution, the US Supreme Court developed this very constitutional ideology to incorporate the idea of being subject to reasonable restriction. And in stark contrast to the argument about the USSR constitution being void of restrictions on rights, the counterargument pointed out quite unequivocally that though there were no restrictions in writing, restrictions existed in essence, since freedom was granted to speak only in favor of one ideology which is inexplicably inherently inconsistent with our values of democracy.

Economic, social, and cultural (ESC) rights have been recognised as judicially unenforceable fundamental principles of state policy, quite unlike civil and political rights which have been recognised as fundamental rights. This judicially unenforceable character was an innovation of the Irish Constitution of 1935 which was later adopted in some countries including India, Pakistan, Burma, Indonesia, and Bangladesh albeit with some dissimilarities. Understandably this was one of the most debated issues in the CA, two members argued that the judicial unenforceability of ESC rights should be lifted and made congruent with all other constitutional provisions in terms of judicial enforceability. However, with reference to China, the USSR, and Germany, it was said in particular that if we looked at socialist countries, we will see that they do not depend on the judiciary for the implementation of fundamental rights which are of ESC nature, rather they carry out the implementation of these rights through representative governance. The chairman of the drafting committee of the constitution emphasised that the necessity of judicially enforceable ESC rights was negated by the duties of the elected representatives of the people, which would in turn ensure that the people are guaranteed these rights. 50 years after its adoption, we must evaluate to what extent this has been fulfilled.

Despite the fact that socialism was considered one of the four fundamental ideals of the constitution and of the state, there was debate regarding the inclusion of private ownership, and when doing so, parallels were drawn along the lines of the constitutions of the USSR and Yugoslavia as examples for the concept of private ownership by succession. This non-mutually exclusive phenomenon was cited to have been seen, even in concept, in the constitutions of the German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia, China and Yugoslavia, where the right to private ownership was recognised, though to a limited extent.

There are five different types of writs known as popular constitutional remedies, namely, mandamus, prohibition, certiorari, habeas corpus, and quo warranto, which originated in the British constitutional law. The Indian and Pakistani constitutions were seen to, word for word, have these writs mentioned in their constitution, while Bangladesh, despite the inclusion and incorporation of these remedies into its constitution refrained from using the Latin terms of these writs explicitly in writing. Facing a lot of criticism of this seemingly unorthodox approach, the chairman of the drafting committee said that the omittance of the Latin names went towards Bangladesh's convenience, by widening the scope through which these writs can be applied, while keeping the very essence of their existence and ridding ourselves of the strict periphery that their names intone. For example, certiorari writ had a limited application only against judicial and quasi authorities and statutory authorities. But, instead of mentioning the term certiorari writ and by saying that, "102.The High Court Division may, if satisfied that no other equally efficacious remedy is provided by law – (a) on the application of any person aggrieved, make an order- … (ii) declaring that any act done or proceeding taken by a person performing functions in connection with the affairs of the Republic or of a local authority, has been done or taken without lawful authority and is of no legal effect," we have enlarged the scope of certiorari writ which can now lie against both statutory authority and any other authority which has a nexus with the affairs of the state albeit not a statutory authority in writing.

Using foreign judgments in interpretation and application is no stranger to the field of constitutional law, neither are the practices of judges in Bangladesh, albeit a relatively recent member of the global legal community, who frequently reference decisions from other countries. Since its adoption in 1972, Bangladesh has had a lengthy history of using foreign judgments as guidance for interpreting its constitution.

In the course of judicial interpretation of constitutional law by the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, foreign judgments have made their way from the global constitutional gene pool to Bangladeshi judgments. Landmark cases include, how the Court in Kazi Mukhlesur Rahman case (1974) has started liberalising locus standi by adopting the concept of sufficient interest borrowing from the cases of Mia Fazal Din (Pakistan) and Blackburn (UK). Ensuing from this case, the liberalisation of locus standi continued till 1996, in Dr Mohiuddin Farooque case where a number of foreign judgments were used, going hand in hand with the Kazi Mukhlesur Rahman case in opening the door for public interest litigation in Bangladesh.

Revolutionarily, the meaning of the constitutional right to life was extended in 1996, which proved quite critical in creating scope for the judicial enforcement of a set of judicially unenforceable constitutional principles on ESC rights, through the fundamental right to life as constituent components of this right. On July 1, 1996, the High Court Division (HCD) of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh adopted an expanded meaning of the right to life for the first time in Bangladesh in the Mohiuddin Farooque Case. The HCD started with an American judgment, extensively referred to and heavily relied on a set of judgments pronounced by the Indian Supreme Court which included Francis Coralie (1981), Bandhua Mukti Morcha (1984), Olga Tellis (1986), Vincent (1987), Vikram Deo Singh (1988) and Subash Kumar (1991).

Reiterating the fact that there is no explicit mention of suo moto writ in the Bangladeshi constitution, there has been a case of constitutional transplantation from Indian constitutional law, where the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, in the Tayeeb case (2011), relied on several Indian cases including the S P Gupta case (1982).

Exercising, quite pioneeringly, the judicial law-making power of the Court, the Supreme Court of Bangladesh in the BNWLA (2009) case, made laws against sexual harassment to fill the legal lacuna which was its constitutional obligation to protect the fundamental human rights of Bangladeshi women. In doing so, the Court relied heavily on the Indian precedent established in Vishaka case (1997) in order to justify the judicial law making for the protection of women against sexual harassment.

In harmony with contemporary, avant-garde, and revolutionary advancements in the constitutional law forum, public law compensation has been another landmark legal development in Bangladesh, through the Court's decisions on Bilkis (1997), Z I Khan Panna (2015) CCB Foundation (2016), where the Court liberally interpreted Article 102 of the constitution considering a set of Indian cases including Rudul Shah (1983) and Nilabati Behara (1993).

These are just some instances of how Bangladesh has utilised world constitutions in forming and developing its constitutional law in the last 50 years. There is still great utility in borrowing different ideas from world constitutions in developing different constitutional issues such as the form of government, election system, powers and functions of parliament and strengthening the parliamentary form of government, inclusion of emerging constitutional rights like the right to scientific benefits, and judicial enforcement of ESC rights. Again, contents of constitutional rights can be developed and concretised in light of constitutional development of rights worldwide. Constitutional borrowing and transplants parallel to worldwide modern constitutional law developments can thus be of great use for the enrichment and nourishment of our constitution.

Muhammad Ekramul Haque is Professor of Comparative Constitutional Law, University of Dhaka

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments