Australia’s Response to the 1971 Refugee Crisis

The Daily Star (TDS): What sparked your interest in researching the events of 1971 in Bangladesh, particularly the connection to Australia, which had largely remained obscure before your investigation?

Rachel Stevens (RS): In 2010, I was teaching a first-year undergraduate history course that covered Asian history from 1500 to today. In the class, we used the textbook A History of Asia by Rhoads Murphey, which is now in its 8th edition and widely used. I still remember reading chapter 20 because it devoted just one paragraph, consisting of four sentences, to summarise the Bangladesh Liberation War.

The treatment of the Bangladesh Liberation War by this esteemed American historian was flabbergasting. And that was it. The moment of astonishment passed, but the memory of this inadequate four-sentence summary stuck with me.

Seven years passed, and now I was working as a historian researching Australia's immigration history. In this work, I did a brief online search of the papers of former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. As an immigration historian focused on the post-1970 period, Fraser is a significant historical figure, especially regarding the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees. So, I went onto the catalogue, thinking I would find material relating to Vietnamese refugees.

I did, but I also found something much more interesting. I stumbled across a transcript of a radio address by Fraser in October 1971, when he was Australia's Education Minister. In his address, Fraser spoke of the 'great deal of attention to the tragic problems in the Indian sub-continent… [that] have caught the imagination and sympathy of many people in Australia'.

Despite being a historian of that period, I had never heard about Australians' deep concern for Bangladeshis during their war of independence. Fraser's comments also reminded me of the Asian history textbook I used in 2010: once again, there was a fleeting reference to a significant world event (the liberation war) that left me with more questions than answers.

I retell these two mundane anecdotes because collectively, they revealed a gap in knowledge. We have the American historian brushing over the significance of Bangladesh's independence war in his textbook; then we have the Australian politician talking about how Australians had been so moved by events far away in Bangladesh. Because these two accounts were so misaligned, I had a hunch that there may be more to the story, which prompted further research into the topic.

(TDS): When and how did Australians become aware of Pakistan's military actions in East Bengal, and how did their reaction evolve over time?

(RS): The news media was the main source of information, particularly the metropolitan broadsheet newspapers and the publicly funded Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Television provided Australians with compelling imagery of the degree of suffering during the war. Radio remained a vital source of information, particularly for Australians living in remote and rural areas (approximately 20 per cent of the population). Journalists not only described the events as they unfolded but also provided political context to help Australians understand the root causes of the war. While the news media was crucial in introducing Australians to events in Bangladesh in the early months of the conflict, from June 1971 civil society organizations, such as churches, NGOs, and activist groups, were leading public discussions on how best to support Bangladeshis.

(TDS): Did your research unveil any noteworthy involvements by humanitarian NGOs in Australia regarding the Bangladesh issue, distinguishing it from responses to previous crises?

(RS): During the war, a schism emerged between older, more conservative NGOs such as the Red Cross, and newer organizations that were far more politicized than their predecessors. The Red Cross movement is known for its impartiality and neutrality in war zones, meaning that during the Bangladesh Liberation War, it insisted on only providing aid to refugees in India and deliberately avoided appropriating blame or taking a side. The provision of apolitical emergency relief was deemed unsatisfactory by younger NGOs, such as Community Aid Abroad (now Oxfam). This NGO saw the war as a decolonial struggle for justice. The political divisions in the Australian NGO scene mirror wider changes underway in Australian society. In the western world, much is written on the 1960s protest movements. In Australia, protest movements came later, in the early 1970s, which coincided with events in Bangladesh.

(TDS): Besides the endeavors of NGOs, how did individuals react to the Bangladesh War crisis in 1971?

(RS): One of the main discoveries of my research is the ways that individuals took matters into their own hands. Rather than waiting for government aid or NGO assistance, disenchanted individuals filled the void. An excellent example is that of suburban housewife Moira Dynon, which I cover in my book. Here is an instance of an educated, well-to-do woman using her high society connections and superior intellect to improve the living conditions of refugees in India. To be sure, Dynon had a long history as a Catholic humanitarian. But when the war erupted, Dynon galvanized the public, engaging in nationwide speaking tours, which educated Australians on the causes of the Bangladesh war, urged them to donate money to charities, and lobbied Australian politicians to increase government aid.

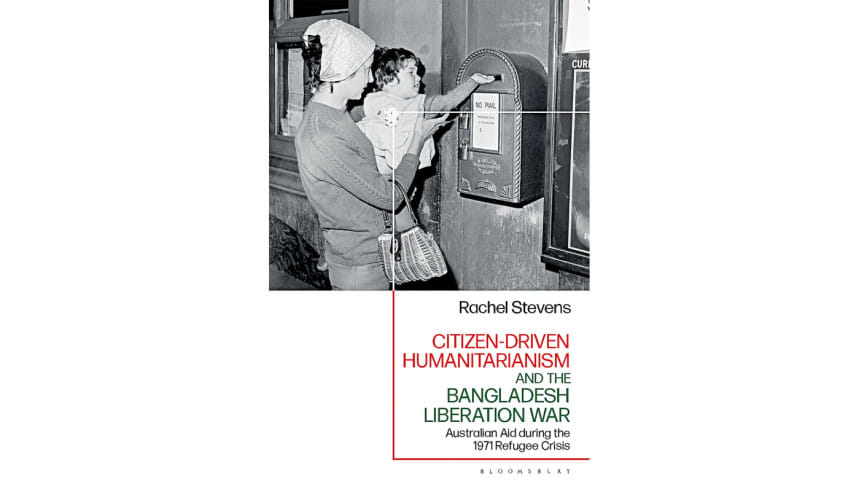

In this interview with The Daily Star, Rachel Stevens, Lecturer in History at the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian Catholic University in Melbourne, shares insights into her research and recently published book titled "Citizen-Driven Humanitarianism and the Bangladesh Liberation War: Australian Aid during the 1971 Refugee Crisis," released by Bloomsbury Academic in 2024.

My research demonstrates the power of the people. When the war started, the Australian government meekly adopted a neutral stance to avoid offending the Pakistani government and their US allies. But within ten months – by January 1972 – the Australian government was leading a coalition of western and eastern nations to formally recognize the independence of Bangladesh. In October 1971, the Australian government also increased their aid commitment to Bangladeshi refugees on three occasions in response to public pressure.

My research shows that the actions of individuals can change government policies that have material consequences for people displaced by war. Rather than criticizing politicians for changing their official position on an issue, we should welcome instances when governments respond to the will of the people.

"Citizen-Driven Humanitarianism and the Bangladesh Liberation War: Australian Aid during the 1971 Refugee Crisis" can be viewed and downloaded free of charge here https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/monograph?docid=b-9781350384743

Interviewed by Priyam Paul

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments