Administrative dynamics in 1971’s War of Liberation

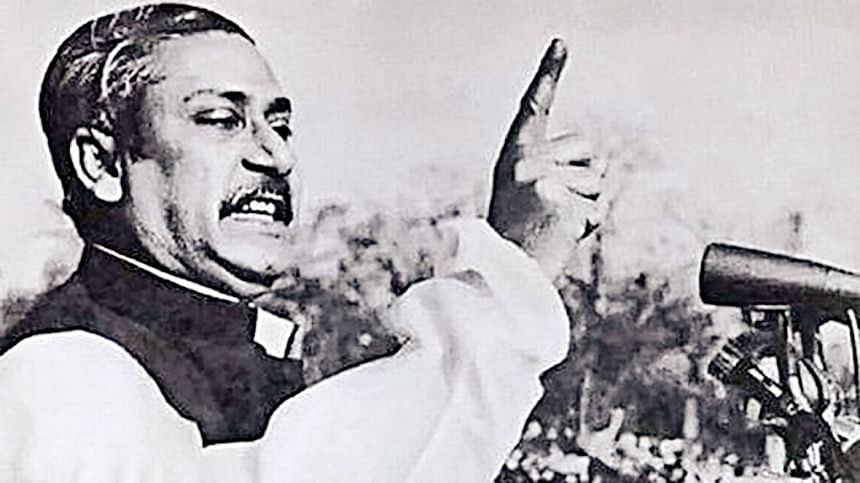

The War of Liberation in 1971 commenced late on the night of March 25th, as the Pakistani army initiated a genocidal campaign from all its cantonments, aiming to seize control of cities amidst the growing resistance movement. However, the Pakistani army encountered unexpected resistance from ill-prepared police, military, EPR, and notably, students, youths, and civilians, who bravely confronted a formal army unprecedentedly. The administrative response to the freedom struggle during wartime was also unrivaled and distinctly different from any historical moment in the subcontinent's transition from one government to the guardianship of another. The government administration neither wholly capitulated to the Junta authority nor staged a coordinated rebellion fueled by the spirit of war against the occupying force.

This paradox underscores the puzzle of an administrative response unfolding without a formally established government to lead the struggle. The scenario mirrored a setting in which administrative authority operated de facto while awaiting formal de jure governance. This duality endured until April 17, 1971, when the government officially materialized through the swearing-in of the cabinet at Mujibnagar.

When examining the accounts of government officials who defied the orders of the Pakistani government in Bangladesh and promptly decided to align themselves with the liberation movement following the crackdown on March 25th, certain common features emerge.

It may be mentioned here that a mere fourteen CSP officers out of approximately a hundred displayed exceptional courage by actively participating in the liberation war. This decision involved substantial risks to their lives, consideration for the safety of their families, and potential sacrifices related to a prestigious and competitive exam.

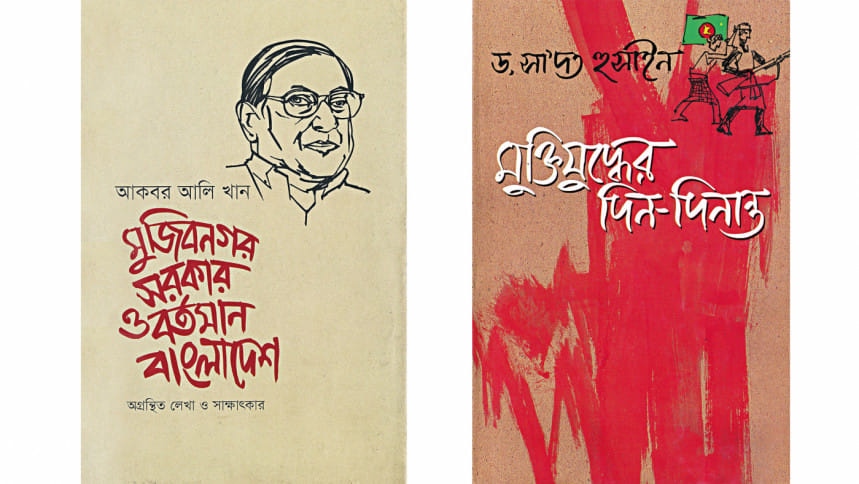

Akbar Ali Khan observed that while some officers may have felt they had no alternative, many had ample opportunities to contribute to the liberation war throughout the nine-month conflict. Akbar Ali Khan and Kazi Rakib Uddin Ahmed, who served as Sub-Divisional Officers (SDOs) in Habiganj and Brahmanbaria at the time, actively engaged in the war effort by aligning themselves with the local Awami League and supporting the resistance movement. Their focus was on maintaining morale, law and order, and organizing provisions such as shelter, food, and arms for the freedom fighters. It's noteworthy that they embarked on these efforts with a limited understanding of the situation unfolding in other parts of the country.

Akbar Ali Khan noted that he issued numerous directives by writing 'on behalf of the Bangladesh Government,' even before its formal establishment.

Subsequently, on April 16th, as the Pakistani army advanced to seize control of Habiganj, both Akbar Ali Khan and Kazi Rakib Uddin Ahmed jointly departed from Habiganj. They, along with the local Awami League leader Enamul Haq Mostafa Shahid, sought refuge in Agartala. In Agartala, they encountered HT Imam, a senior official, who had initially organized the resistance movement in CHT but, regrettably, couldn't sustain it, leading him to also seek refuge in Agartala.

The government administration neither wholly capitulated to the Junta authority nor staged a coordinated rebellion fueled by the spirit of war against the occupying force.

In the southeastern region, certain government officials took a principled stand by rejecting the authority of the Junta-controlled bureaucracy. Opting for independent resistance against the occupying army, they endeavored to steer their territory in support of the Bangladesh government, all while grappling with the looming threat of military occupation.

Despite their efforts, their administration faltered over time, leading them to seek refuge in Kolkata. Their "liberated zone" succumbed to Pakistani army control, prompting them to eventually integrate into the Mujibnagar administration after the government's formal establishment.

Sadat Hussain, a junior CSP officer serving as Assistant Commissioner in Jessore, played a pivotal role in orchestrating the war resistance primarily centered in Narail. In his war memories, he documented numerous firsthand accounts from various officers within that zone, providing valuable insights into the challenges and triumphs of the wartime efforts. He chronicled his entry into India on May 22, recounting a harrowing experience of crossing a river while grappling with intense disappointment. Along the border, he faced severe torment from local touts, and throughout the journey, he encountered significant hardships at the hands of several Pakistani collaborators.

Before the war, on March 23, Sadat Hussain convened a private gathering with his fellow officials in Jhenaidah, where they collectively pledged to fight for independence. This commitment was clearly manifested in their actions when the Pakistani army waged war against Bangladesh.

Furthermore, Waliul Islam, serving as the SDO of Magura, not only engaged in the war effort but also assumed the position of Deputy Commissioner (DC) in Jessore in December, contributing significantly to the liberation of Bangladesh.

Meanwhile, Kamal Siddiqui, the SDO of Narial, assumed leadership of the resistance movement, rallying the people in his region to fervently engage in the war effort. He passionately advocated for the establishment of training centers in villages following the crackdown. Ultimately, he became part of the Mujibnagar government in exile.

Historian Mahboobul Alam, in his acclaimed book "Muktijuddher Itibritto," highlighted that while the Awami League exerted maximum pressure on the Pakistani Junta through their movement, their preparations for the 1971 war were minimal. The initial administrative response to the War of Liberation in 1971 also reflected apparent unpreparedness but later gained momentum through the sheer will of the people.

Priyam Pritim Paul is a researcher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments