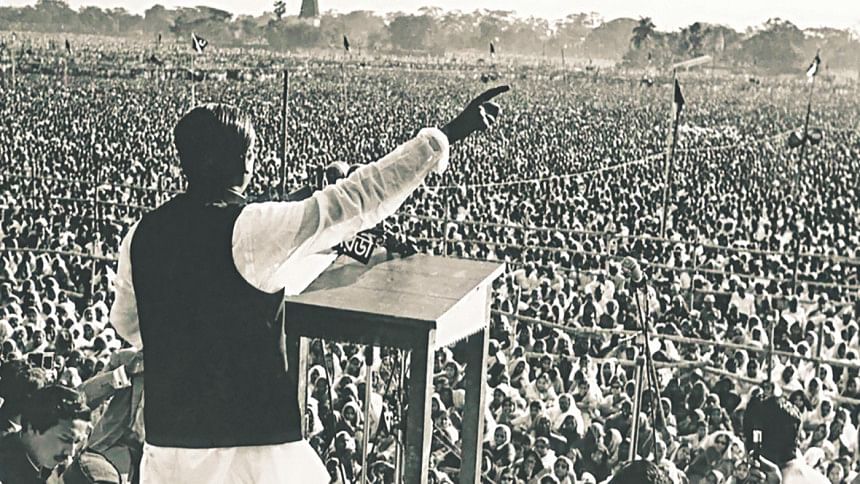

Bangabandhu’s Vision of Independence

One of the most striking characteristics evident in The Unfinished Memoirs is how the young Sheikh Mujibur Rahman showed immense courage and resolve in standing up against arbitrary and overpowering forces, and how he became a figure who spoke truth to power repeatedly. In the process, he developed into Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the kind of leader able to inspire others to drive out the brutal and powerful occupation army that had come to bloody his beloved Bangladesh in 1971. Again and again in his autobiographical writings we see how he is ever ready to stand up and protest against injustice and willing to sacrifice anything and everything for his country and its people. This is why at one point of his narrative, when he feels that Moulana Bhashani had acted unbecomingly in public when Mr. Shamsul Huq had been asked to preside over a meeting instead of him, Bangabandhu says he nevertheless retained his respect for the Moulana, since he had sacrificed so much for the cause of the people by that time. As Bangabandhu notes on the occasion, "To do anything great, one has to be ready to sacrifice and show one's devotion. I believe that those who are not ready to sacrifice are not capable of doing anything worthy. I was able to come to the conclusion that to engage in politics in our country one must be ready to make huge sacrifice and show one's devotion" (137). Some years later, when he had become the father of two children, we find Bangabandhu thinking thus just before he is going to be arrested yet again:

"I was getting more and more attached to my children. I didn't feel like leaving them but I would have to. I had consecrated myself to the cause of my country—so what was the point of becoming sentimental about my family? If one loves one's county and its people one must be ready to sacrifice something and in the end might have to give up everything (159)."

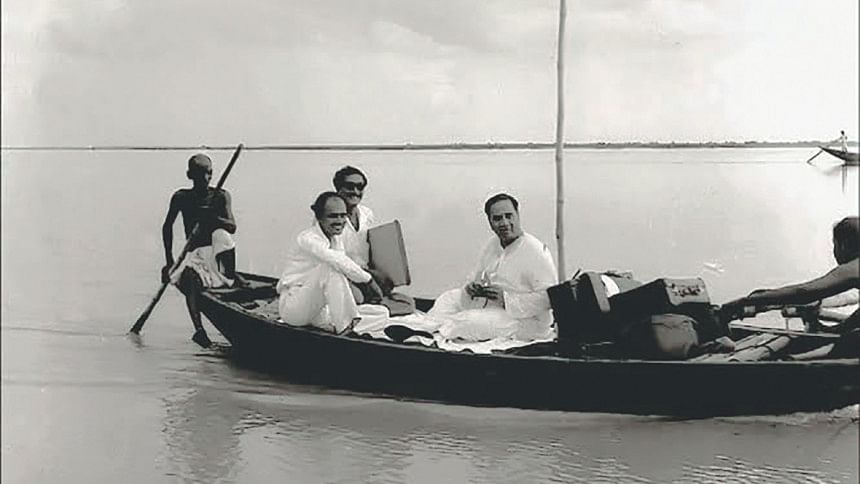

Bangabandhu's life, as recorded in The Unfinished Memoirs, is one of such continuing sacrifices, unremitting courage, and unswerving commitment. In it he demonstrates time and again the ability to bear immense pain for a cause and endurance and immense capacity for sheer hard work. The narrative allows us to see how in addition to the sacrifices he had made in terms of family, education and finances, he had to work endlessly and undergo constant travel. He endured sleepless nights, physical pain as well as deprivation of all sorts in his dedication to the cause of his people. During the Bengal famine, for example, he laboured for some time in gruel kitchens in Kolkata; a little later we find him involved in relief work in Gopalganj.

Whatever the young Mujib was involved in, he was hard at work, completely focused on the job at hand, and convinced that what he was doing was important for the future of his country and its people. Such commitment and capacity for hard work, coupled with organisational skills, will explain why we see him being made secretary of different committees at different levels, whether as a youth in Gopalganj, or a student in Kolkata. It is for such complete commitment that we find him getting involved in Muslim League politics in the city, or becoming a rising politician in post-partition Dhaka. After he came to Dhaka he very quickly quit the Muslim League and rose to prominence in the Awami Muslim League that he had helped create.

When in the first stage of his political career he had launched headlong into the movement to create Pakistan, he appeared to have kept in view the sacrifices made by other Bengali Muslim leaders before him; he always had a clear sense of history and knew what it could teach us. He thus tells us at this point of his story that he was very conscious of the Sepoy Mutiny and the Wahabi movement and very much aware of "how the British had snatched away power from the Muslims and how then "the Hindus had flourished at their expense" (23). He is aware too, he tells us in the same section of his narrative, of the Wahabi movement, Titu Mir's rebellion and Haji Shariatullah's Fariazi movement. A little later, he underscores the necessity of breaking free from the clutches of "Hindu moneylenders and zamindars" (ibid).

The implication of such passages are clear; Bangabandhu is surely saying that as a Bengali Muslim ready to campaign for Pakistan in Kolkata, he knows that he has models before him in various Muslim movements and leaders whose achievements are recorded in Bengal's history. He is fully aware of the resistance undertaken over time against British colonialism, Hindu feudal elements, rapacious financiers and business men of all religions who preyed on Muslim peasants and workers. It was no doubt his consciousness of the way ordinary Bengali Muslims suffered at the hands of Hindu Bengali Brahmins that had on a previous occasion made him take on the Hindu Mahasabha leader of Gopalganj town, Suren Banerjee and his men. This was the occasion for the young Mujib's first experience of jail as well as of police and court proceedings.

But as a young and budding leader he was always willing and ready to stand up against all men with feudal mindsets, Hindu or Muslim. In the formation of Bangabandhu's consciousness, anti-feudal as well as communal emotions played a major part, as did his awareness of the negative roles played by such men in Bengal's history. This was clearly why he endorsed Mr. Abul Hashim's manifesto for the Muslim League in which the veteran ideologue argued that the zamindari system should be abolished. The budding leader came to the realisation that he would have to take a stand against the feudal Muslim leaders of East and West Pakistan's Muslim League because these people were essentially lackeys of the British, opportunists, anti-people, selfish and heartless. It was with such knowledge that Bangabandhu would launch himself in the movement to wrest control on behalf of all Bengalis—Hindus as well as Muslims—in the next phase of his political career in the newly created province of East Pakistan. And he would do so with the same kind of courage, indomitable spirit, self-sacrificing mentality and commitment he had shown in the movement for Pakistan under Mr. Suhrawardy's leadership in Kolkota.

The Unfinished Memoirs is thus very much the story of a spirited young politician learning about how he should take his people forward on the road to independence as he plunged deeper and deeper into Bengal politics. It is very much a narrative revealing Bangabandhu's instinctive identification with ordinary people and sense that he belonged to them and not in the pockets of distant rulers. It is also about his realisation that the real enemies of a country are those who exploit people—Brahmin or Muslim landlords, moneylenders and businessmen-politicians. Patrolling the streets of Kolkata with a gun in his hands to protect Muslims during the riots that took place there before Partition, he soon realised that though a Muslim Leaguer it was his responsibility to save Hindus as well as Muslims stranded in riot situations. The young Mujib's intense involvement in saving Bihar riot victims afterwards left him with an even greater appreciation of the havoc caused by communal feelings and the need to rise above them to work for our common humanity.

Back in his country after Partition and deeply involved in East Pakistani politics, we find him stressing the importance of "ensuring communal harmony in Pakistan for the nation's future" (109). He now has the additional realisation that maintaining peace between people of different religions inside Pakistan was essential since religious riots had chain reactions, inevitably creating an endless flux of refugees and immense suffering for ordinary people everywhere. Later, when in jail in Faridpur for an extended period of time where he met the philanthropist Chandra Ghosh, who had been put there unfairly by bigoted politicians and administrators, the then ailing Bangabandhu said to him in tears, "'I always treat people as people. In politics I make no distinction between Muslims, Hindus and Christians; all are part of the same human race" (190).

Plunging even deeper into East Pakistani politics, Bangabandhu realised that the only reason for him to be in politics was that it would give him the opportunity to work for ordinary people; it was only their causes he should stand up for. One of my favourite passages of The Unfinished Memoirs depicts the young Mujib reacting against the arbitrary imposition of the "cordon" system in rural East Pakistan to restrict inter-district food grain movement. How would the decision-makers in Dhaka and Karachi know how such a restriction could affect "dawals" or day labourers who worked in rice fields outside their home districts and who received a part of the harvest for the work that they did, which they would then take back home after harvesting was over? Immediately, the young Mujib organised protest meetings against such an unjust and arbitrary measure and even rushed to Khulna to "lead a procession of dawals" there (111). Repeatedly, at this stage of his political career, we can see Bangabandhu getting involved in such situations on behalf of ordinary people and pitting himself against rulers based in far-off cities and walled places who knew little or nothing about their lives but who imposed decrees on them ruthlessly and capriciously. At one such point of Bangabandhu's narrative he indicates that any leader who has surrounded himself with officials and cut himself off from ordinary citizens would inevitably be alienated from them and would alienate them as well.

In 1948, while travelling from one part of the country to another on organisational work, Bangabandhu learnt that lower class employees of the University of Dhaka were on strike for more pay and better facilities. Consequently, he joined them and the students campaigning on their behalf. He had felt then that it was easy for him to see that "they had taken the measure because the people in power had decided to ignore their demands" (119). His experience at this juncture, as with the landless farmers affected by the cordon system, convinced Bangabandhu that the Muslim League was losing support rapidly because of its anti-people policies and administration. When the young Mujib asked himself some months later why the party that had been "so enthusiastically supported by people in 1947" could be defeated so easily in record time, the answer that came to him immediately was that "it could be put down to coterie politics, rule of tyranny, inefficient administration and absence of sound economic planning" (127).

Every educated Bangladeshi should read the Unfinished Memoirs, if only because he or she can deduce from it the steady evolution of his political philosophy. The excellently paced narrative reveals the way Bangabandhu began to evolve the founding principles of Bangladesh and realise the need for good and people-focused governance from close encounters with politicians and government officials. As he get to know the people of East Bengal, and as he went from district to district and town to town there after the Kolkata part of his educational and political life was over, he began to evolve a vision for Bangladesh that would lead him closer and closer to its founding principles—secularism, nationalism, democracy and socialism. Looking at the Muslim League government at work in East Pakistan, Bangabandhu came to understand clearly why government must be by the people, for the people and of the people, why democracy worked best, and why any government in power should work on democratic assumptions.

There are thus many lessons we can learn from The Unfinished Memoirs that are of timeless value. The young Mujib realises, for instance, in 1950 that the problem with Liaqat Ali Khan was that "he wanted to be the prime minister not of a people but of a party" (144) and "that a country could not be equated with any one political party" (ibid). More than once, Bangabandhu had the feeling that the Muslim League government was asking for trouble by trying to smother any opposition to it. When he met Khwaja Nazimuddin in Karachi at that time, the young Mujib had the temerity to tell the Prime Minister of Pakistan: "The Awami League is in the opposition. It should be given the opportunity to act unhindered. After all, a democracy cannot function without an opposition" (213). Faced with communal riots against Kadiyanis and Ahmadiyyas in independent Pakistan, and the intolerance displayed in parts of the country against these sects and people of other religions, Bangabandhu stresses that Islam taught us not to punish even non-believers. Moreover, when he emphasises that Pakistan was supposed to be a democracy where people, "irrespective of religion were supposed to have equal rights" (244), he is indicating clearly his belief that he would like to be in a democracy where all were treated equally by the government and by the law.

In Dhaka and in East Pakistan, and supposedly in a completely independent country where people were supposed to have all kinds of human rights, Bangabandhu was shocked to see attempts underway to deculturise East Pakistan's Muslims, strip the "Bengali" part of their identity as far as possible, and make them adopt the Urdu language for state occasions. By early 1948 the young Mujib and fellow members of the Student League had joined the members of the Tamaddun Majlish in opposing Muslim League moves to make Urdu the only state language of Pakistan, and in demanding that Bengali be made one of the two state languages. He soon spoke up on the topic on every possible occasion, and joined meetings and demonstrations organised on the issue. Although in jail in February 1952, Bangabandhu was in constant touch with organisers key to the Language Movement. He had come to believe that the movement would succeed since all Bengalis were supporting it and since, as he puts it, "no nation can bear any insult directed at its mother tongue" (197). Bangabandhu records in his memoirs not only his shock and regret at the death of the language martyrs on February 21, but also his feeling that the blood they had shed would not go in vain. As he puts it, at a time in Faridpur prison when he saw little hope for himself, "I thought since our boys had shed blood they would end up making Bengali the state language even though I myself would never be able to see that day" (203).

Throughout The Unfinished Memoirs, Bangabandhu records his love of everything Bengali. He was deeply attached to Bengali culture as a whole and the Bengali language in particular. When he heard Abbasuddin's song in a boat on the Meghna, he tells us that he was simply mesmerised by the beauty of the whole scene. When in Karachi a few years later, he is reminded by its setting of how green his beloved Bengal was, and how beautiful, compared to the "pitiless landscape" of the West Pakistani one. This makes him compare the hard mindset of West Pakistanis to the softness of the Bengali temperament and makes him conclude "We were born into a world that abounded in beauty; we loved whatever was beautiful" (214).

In the Peace Conference he attended in China in 1951, Bangabandhu spoke in Bengali, reasoning thus: "Chinese, Russian and Spanish were being used in addition to Bengali, so why should I not speak in Bengali?" (230). Mr. Ataur Rahman Khan had delivered his speech in English before him, but it was Bangabandhu's nationalistic feelings that made him speak in Bengali. This was perhaps the first time the language was used in an international conference held on such a scale. As Bangabandhu wrote on the occasion, "I could speak English fluently but I felt it was my duty to speak in my mother tongue" (230). His growing conviction that autonomy was needed for East Bengal was now linked to his linguistic nationalism. This is why in a passage of his memoirs that deals with the political situation in 1953, Bangabandhu writes clearly, "We were bent on making Bengali a state language and would not compromise on these issues" (247).

And so as he immersed himself in the politics of Pakistan after coming back from Kolkata, Bangabandhu had come closer and closer to the view that Bangladeshis needed a country where secularism, democracy and the kind of nationalism based on upholding the Bengali language and celebrating Bengali culture must take roots. As for the fourth pillar of our 1973 constitution, it should be clear to readers of this piece by now that he felt strongly that inequality in all spheres should be minimised in all fronts—political, cultural or economic ones. Not only was he against feudal ways of thinking and the zamindari system, he was always inclined to favour the equitable distribution of resources. This is abundantly evident in the pages of Unfinished Memoirs devoted to the "New China" that he visited for the Peace Conference, as well as his long discussion of the socio-economic experiment he saw there, and the comparison that he drew between it and contemporary Pakistan in his "New China" book. At the end of his description of his visit to China in The Unfinished Memoirs, he says unequivocally: "I myself am no communist; I believe in socialism and not capitalism. Capital is the tool of the oppressor" (237). Analysing the defeat of the Muslim League at the hands of the United Front in 1954, Bangabandhu observes that it was no good to try and fool the people by using religion as an excuse to exploit and dominate others. He notes that what "the masses wanted is an exploitation-free society and economic and social progress" (263). He knew from China's experience that the forces of capital would always stand in the way of whoever wanted to establish such a society.

The Unfinished Memoirs is thus not only a record of the first 34 years of Bangabandhu's life but also a book depicting the evolution of his political thinking that can be of immense use for us at this time as we attempt to restructure our society and take our country further along the road to the future. It is also a work telling us that we need to restore the four pillars of the country—nationalism, socialism, democracy and secularism—fully if we are to build the kind of Shonar Bangla that Bangabandhu dreamt of. Of course to do so we should realise that we will need the willingness to sacrifice, demonstrate the capacity to do hard work, and exhibit courage, determination and organisational skills. That is to say, we will need to emulate the young Mujib in every way. We will also need to have his kind of love for the Bangla language and the country, and his respect for all of its citizens, regardless of their religion or class positions. Like him, we must demonstrate the courage to speak up and say truth to power, whether within the country or internationally; for dark forces will always deter us and attempt to take us away from our founding principles.

But the Unfinished Memoirs indicates too that to achieve such goals we also need humility, the courage to admit that we may have taken the wrong course every now and then, and the alertness to readjust our course when we need to. As Bangabandhu tells us at one point of his narrative, "If I have been mistaken or if I have done wrong I have never had difficulty in acknowledging my mistake and expressing my regret" (85). As he also says at the conclusion of the passage: "When I decide on doing something I go ahead and do it. If I find out I was wrong, I try to correct myself. This is because I know that only doers are capable of making errors; people who never do anything make no mistakes" (85).

Fakrul Alam is UGC Professor, Department of English, and University of Dhaka. He received the Bangla Academy Puroshkar (Literature Award) for Translation in 2013. His publications include The Essential Tagore (Harvard UP, 2011; with Radha Chakravarty); Imperial Entanglements and Literature in English (writer's ink: Dhaka, 2007); South Asian Writers in English (Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2006) and Jibanananda Das: Selected Poems (UPL, 1999); Other works include translations of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's Unfinished Memoirs (Dhaka: UPL, New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2012) and Prison Diaries (Dhaka: Bangla Academy, 2016) and Ocean of Sorrow, a translation of the late nineteenth century Bengali epic narrative, Bishad Sindhu (Dhaka: Bangla Academy, 2017). Recent publications include Once More into the Past (Dhaka: Daily Star Books, 2020) and Ballad of Our Hero Bangabandhu, a translation of Syed Shamsul Huq's Bangabondhur Bir Gatha. Dhaka: Bangla Academy, 2019.

Part of the lecture was published previously in The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments