Death need not be painful: Palliative care in Bangladesh

In November 2016, nine-year-old Asif was admitted to the only hospital which treats child cancer patients in the country. He was prematurely released from the hospital, with a few months of treatment still left to receive. “I have a small job in a village. There was no way I could afford to rent a place in Dhaka to resume my boy’s treatment. I had no clue where to go,” shares Anwar Hossain, father of Asif, while recounting his hopelessness during his child’s costly cancer treatment. He frantically asked for help from the nurses at the hospital and learned of ASHIC, Foundation for Childhood Cancer.

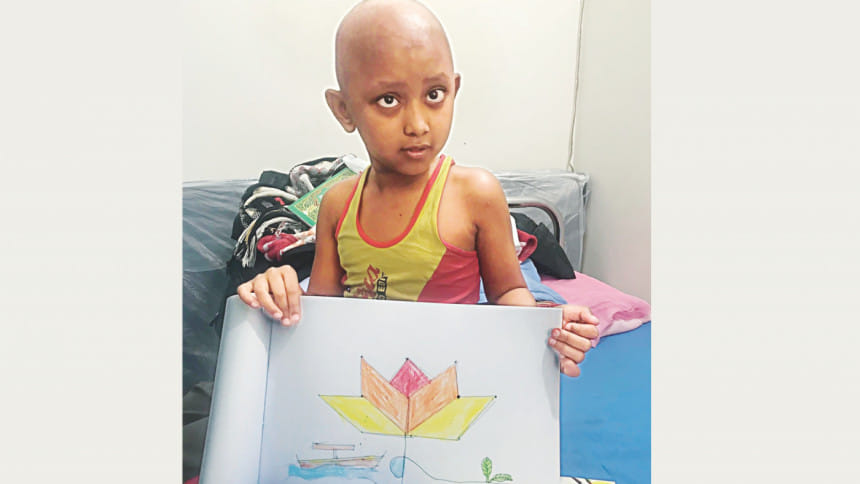

The ASHIC shelter provided him and his family with free food and accommodation as Asif continued three and a half years of rigorous treatment at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU) Hospital. However, any hopes for Asif’s recovery came crashing down as he suddenly relapsed, with no scope for further treatment. There was nothing else Anwar could do but to admit his distressed child to the ASHIC Palliative Care Unit (PCU).

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as an interdisciplinary caregiving approach that helps with pain management for terminally ill patients through medication and psychosocial support for both patients and caregivers. The care begins right when the disease is first detected, and while it does not necessarily add to a patient’s lifespan, it ensures their last days are not full of pain and suffering.

“Not only children, but cancer patients of all ages should receive palliative care. I cannot put into words just how much care and support guardians can obtain from palliative care centres,” says Anwar. After three months of receiving pain relief and counselling in the ASHIC PCU, Asif breathed his last on May 10, 2019.

According to the National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) 2014, 75 percent of cancer patients experience tremendous pain. Even though pain during terminal diseases is inevitable, that does not mean that patients must suffer without trying to relieve some of it. That is where palliative care steps in. Dr Rumana Dowla, Consultant, Palliative Medicine, United Hospital, and Founder Chairperson, Bangladesh Palliative and Supportive Care Foundation (BPSCF), says, “In more than 70 percent of our patients, the cancer has already spread. At this incurable stage of the disease, palliative care is mandatory. It designs a holistic approach for care by considering the physical, mental, spiritual and social needs of both patients and their families.”

“Why don’t you just let me die instead of making me go through such pain?” was the kind of complaints Salma Choudhury, Founder Chairperson, ASHIC, Foundation for Childhood Cancer, would receive from patients who had no more hope for treatment, and were denied further care from hospitals. This kind of care is especially important during the last stages of a terminal disease, since pain relief medication such as morphine and opioids is not provided to patients before this phase. Most hospitals in Bangladesh that provide cancer treatment do not include palliative care. Private centres rather take advantage of this scenario and overcharge these patients in agony, for basic palliative care services.

In many cases of treatment of terminally ill patients, the needs and wishes of the patients themselves are neglected. Dr Rumana Dowla shares, “It is important to respect the autonomy of the patients. It is their right to design their own care. We need to ask the patients how they want to spend the last few days of their lives; whether they want to stay at home or try all other forms of treatment.” Continued treatment for incurable diseases can cause unnecessary financial burdens on families, and so Dr Rumana Dowla also suggests not keeping patients in the ICU during the last stages of the disease. “Caregivers should also be informed about Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) and Do Not Intubate (DNI) method, which is advanced care planning,” she adds.

The primary palliative caregivers in hospitals or health centres are nurses, and one of the biggest issues with palliative care in Bangladesh is that, even after much effort, it has not been included in our undergraduate or nursing medical curriculum. “Palliative care is a speciality, and the university has a five-year speciality residency programme in palliative medicine,” says Dr Nezamuddin Ahmad, Professor, Department of Palliative Medicine, BSMMU. Apart from this, there are private initiatives such as a basic certificate course in palliative nursing in BSMMU and also a specialised palliative training course for nurses at Ayat Skills Development Centre.

Taking care of the psychological and emotional well-being of patients and caregivers is as important as taking medication for pain management. “Art therapy, music therapy, hypnotherapy and acupuncture are complementary alternative therapies which help heal the patients,” says Dr Rumana Dowla. According to the findings of a research paper titled “Art Therapy to Improve Quality of Life of Cancer Patients and Their Carers in Bangladesh,” art therapy caused drastic improvements in psychological and social aspects in both patients and caregivers. One such programme for art therapy in Bangladesh can be found at BPSCF’s “Healing Through Art” project. For children, Salma Choudhury took a different approach to psychosocial support. “In government hospitals in Dhaka, Chattogram, Sylhet and BSMMU, we have set up play centres where child patients can enjoy playing with toys, and they also have company, instead of spending their entire time lying on beds,” she shares.

Even though palliative care has still not been included in the National Health Policy, there has undoubtedly been vast progress in Bangladesh in the past few years. “The government has released a national guideline for palliative care on November 24, 2019 which is a fantastic milestone achievement,” says Dr Nezamuddin Ahmad. However, he also emphasised that implementation is crucial, and so a national strategy should be set up, following the guideline.

A few other recommendations by Dr Nezamuddin Ahmad include raising awareness on palliative care throughout the country and creating a community-based approach, with the introduction of community clinic programmes. “The [palliative medicine] department caters to a maximum of six to eight thousand patients, but more than 600,000 people in the country need this care,” he mentions. This is why he suggests setting up palliative care services which are hospital-based as well as home-based, with proper training provided to both formal and informal caregivers. The final recommendation is to set up a National Institute of Palliative Medicine that can lead the way for palliative care in Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments