Early dreams and rude awakenings

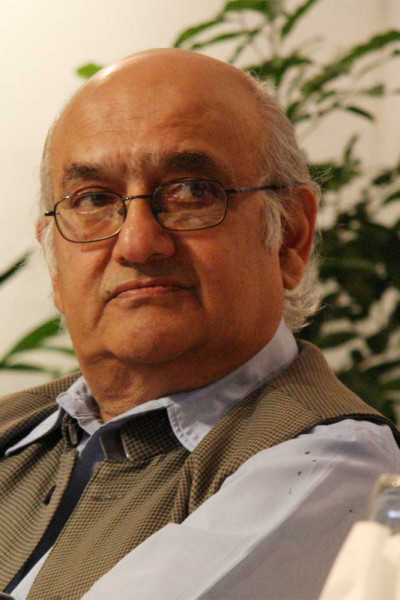

Prof Rehman Sobhan (RS) continues to amaze. Even at this ripe young age, his pace has not slackened, his gaze has not dimmed, his voice has not faltered as it retains its keenness, relevance, and moral clarity. He has earned his place as the elder statesman of our scholarly and activist communities—a heroic, enduring and inspiring presence in our midst.

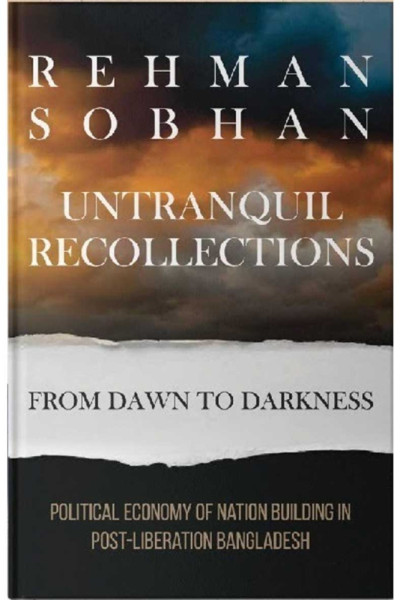

He has also become the pre-eminent chronicler of his times. This is always a tricky terrain to navigate, more so when important personalities and controversial issues are involved, where narratives become "sacrosanct" (Page 7) and discourage interrogation. In the hypersensitive and polarised environment of the country, writing contemporary history becomes not only a "contested," but a "risk-prone" enterprise (Page 8). But RS "pulls it off," and does so in style and with authority.

This is not accomplished because of his writerly craftsmanship, nor his political instincts learned and honed over the years, but by the qualities of scholarly integrity, personal humility and natural graciousness that are inherent in him, and reflected in the book.

The volume begins with that "exhilarating" and "epic moment" of his return to Dhaka on December 31, 1971. Little did he know that in less than four years, he would leave the same city and seek refuge in Oxford, UK. This is a brave and honest effort to come to terms with that tumultuous period in our history.

This is our story as well—the generation of students at DU in the late 60s, who participated in the political and military struggle for freedom, and shared the same passion to build the socialist and democratic Sonar Bangla invoked by Bangabandhu and fervently embraced by us. But we failed. What happened? That question haunted us and, often, mocked us.

In the giddiness of victory and the idealism of youth, we had never actually understood the enormity of the task before us. We had assumed that the obvious economic and social problems we faced at the time were practical problems, which could be resolved through some effort, imagination and sacrifice. What we did not realise—as this book explores—were the political, psychological, administrative and other slippery slopes that had doomed the socialist "moment."

While this is a rich and provocative analysis of that entire period, it is really a discussion of THAT failure which speaks to our generation most compellingly. Hence, it is this aspect of the book which will be the focus of this essay, more as personal reflections rather than a "review."

Reading the book makes us realise that there were deeper, subtler, more treacherous issues we did not understand, such as institutional jealousies, jurisdictional frictions, and leadership jostling (particularly the scramble for nearness to Bangabandhu). The lack of coherence and synchronisation was painfully reflected in persistent inter-ministerial wrangling. RS refers to the intense bickering, which he once describes as a "gladiatorial contest," even between the ministries of planning and finance, while both were under the same minister, the perceptive and talented Tajuddin Ahmed.

This lack of coordination was both painful and hilarious. RS recounts the story of his trip to Chhatak Cement Factory, when he saw that large inventories of cement had been stockpiled because of patron-based distribution bottlenecks, while just on the other side of the river, work on the Sylhet Pulp Mill, being constructed on German credit, was at a standstill because they did not have enough cement to complete their project (Pages 195-196). His efforts at "intervention" resulted in complaints about "overstepping jurisdiction."

Similarly, he was incensed when he realised that the housing project that had been planned in Mirpur had not progressed at all, and the allocations in the Annual Development Plans (ADPs) had been used just to pay for the hugely inflated price of the land controlled by influential people (Pages 175-178).

There were many such examples. They proved, as Burns had noted, that "the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry"—particularly when the left hand of planning does not know what the right hand of implementation was doing.

The members of the Planning Commission also faced difficulties dealing with senior bureaucrats who resented their power (perhaps their abilities and ideals as well), as well as from junior officers given to traditional inertia, rather than the promptness and initiative the circumstances demanded. RS suggests that this distance may have been heightened by the members' own inability or unwillingness to build bridges either because of their egos, their access to Bangabandhu, or their political inexperience.

But it was not merely management inefficiencies and institutional gridlock that haunted the transition to a socialist economy. The book appeared to confirm the impression long suspected—that the concept itself had not been clarified to the larger body of political stakeholders, nor its "ownership" distributed more widely. It became a word or a slogan, but not a programme or a strategy for which the nation had been mobilised.

Moreover, there were questions about what the concept meant. It is possible that Bangabandhu (who had written admiringly about China after his visit there in the early 1950s, who may have disliked capitalism as an exploitative system, but whose references to socialism as an ideal had been a bit vague and infrequent) had, in all likelihood, visualised it merely as creating an inclusive and just society that would bring "smiles to people's faces."

The Planning Commission had assumed that it involved the pursuit of nationalisation and redistributive objectives, where the "commanding heights" of the economy would remain under state control, which could all be accomplished through appropriate policy frameworks and institutional support.

Traditional upholders of the notion had conceived it as a "revolutionary undertaking," requiring a theoretical understanding of the dialectics of class struggle and the materialist conception of history, and difficult to achieve under an unprepared leadership with its petty-bourgeoisie background and orientations.

Bangabandhu's approach to the concept appeared to be emotional; to the commission, the challenge was intellectual; to the hard-line leftists, the commitment was ideological. They may have been reading the same book, but probably not the same chapter, and were certainly not on the same page.

Bangabandhu's public utterances on the subject became less vigorous. The nimble-minded and progressive Tajuddin was distracted by other concerns, and distanced himself from the commission. Political leaders were much too busy consolidating their positions and rewarding their followers in a rather free-for-all environment. Trade union leaders, considered to be the natural allies of the nationalisation policies, were consumed by internecine conflicts over power and privilege. Students, freedom fighters, and cultural activists faded away since their belongingness was neither activated nor even sought. Intellectuals withheld support either because the initial efforts were considered to be too radical by some, or too timid by others. Even Maulana Bhashani, with his long roots in peasant and populist activism, became more of a critic than a supporter of these measures.

Opponents of the concept such as the new "brief-case capitalists," the "indenting entrepreneurs," and the "dispossessed owners of the nationalised industries," became increasingly active and gained traction. Plans for agrarian reforms were completely shelved for reasons of "practical politics." The commission note on the First Five-Year Plan, which contained the most comprehensive discussion of goals, benchmarks and policies, was hardly debated in parliament and given only a cursory reception in the cabinet.

The entire notion of "socialism" gradually began to be viewed as an "academic" exercise—in the worst sense of the term. Some Awami League stalwarts began to believe that "Bangabandhu was led down the garden path on the issue of nationalisation by the professors in the Planning Commission" (Page 114).

Moreover, it was widely believed that the nationalisation programme was a disaster. RS points out that in spite of various and obvious difficulties, its performance was really not too shabby. In Chapter 10, he details the aggregate success it achieved in several (though not all) sectors. However, the damage to its reputation had been done, and it was lethal.

The "gang of four" in the commission began to feel frustrated and alienated. Dr Nurul Islam, the liberal "technocrat," Dr Anisur Rahman, the "idealist," Dr Mosharraf Hossain, the "pragmatist," and RS, the (incurable) "optimist," were all disappointed with the level of support their ideas generated. Even the international solidarity that they had expected from socialist countries proved to be ephemeral and elusive (Pages 243-247). Consequently, they began to plan their exit strategies. By late 1974, nearly all had left or were on their way out. Their grand experiment had collapsed.

But while the concept of socialism might have been a bit complicated, and carried some baggage, the issue of democracy was simpler, and integral to the values and vision which defined the nationalist struggle. The reason why even that was largely abandoned through the institutionalisation of BAKSAL is clearly a more complex issue.

The book does not avoid it. Indeed, RS expresses his anxiety and dismay as those events unfolded. But it does not receive the same engaged attention as the unravelling of the economic plans does. His relative indifference to this issue is understandable, since this was not his area of expertise or focus, and the subject may be more delicate. But clearly both outcomes were related and had been prompted by similar factors and dynamics.

RS also refers to the rising anti-Indian mood in the country. It would be difficult to determine if this had been caused by the pre-existing sentiments that had been nurtured as an article of faith during the Pakistani period and still resonated among many in Bangladesh, or by the challenges and failures of the state leading people to blame an external agent, or the attitudes and behaviour of India itself that deepened early suspicions and concerns. Similarly, whether people became more communal as a result of anti-Indian feelings or more anti-Indian because of their communal predispositions cannot be clarified. But both were palpable and contributed to the government's unpopularity, since it was considered to be too beholden to Indian interests. (Awami League's perceived over-closeness to India was mined and manipulated to cunning advantage by successive regimes and communal forces).

In the context of the corruptions, mismanagement, political tensions, bureaucratic infighting, law and order problems, the proliferation of "bahinis," external pressures (the oil crisis in 1973, the rise of international food prices that led to the famine the next year), and the "crisis of rising expectations" (when people had expected too much and received too little), Bangabandhu may have felt a bit overwhelmed, besieged, impatient, and alone with his back against the wall. BAKSAL may well have been his cry of desperation and a plea for help from the public—the one constituency he knew, loved and trusted.

In less than a year of BAKSAL, the father of the nation, the very symbol of our dreams and struggles, lay in a pool of blood following a dastardly and brutal attack on his entire family. The subtitle of the volume "From Dawn to Darkness" is, thus, both poignant and accurate.

This is a sad book. While it covers a lot of territory, presents characteristically clever insights and astute analysis, and is written in the inimitable style and dry wit of RS, it is ultimately a sincere and candid reckoning with the reality of some unsettling failures. Hopefully, this will inspire a fuller, richer and more objective discussion of how our soaring dreams turned into a grim nightmare so quickly.

What is remarkable is that, in this book, there are no axes to grind, excuses to offer, fingers to point, beans to spill, canards to skewer, patrons to placate, demons to slay, or agendas to advance. It opens a window into that intriguing and chaotic period which gradually assumed the dimensions and character of a Dickensian tragedy ("it was the best of times, it was the worst of times … it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair").

This book should not only be read—it must be studied.

Dr Ahrar Ahmad is professor emeritus at Black Hills State University in the US, and director general of Gyantapas Abdur Razzaq Foundation in Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments