Fazlul Huq and the Bangalee Muslim question

The phrase "Bangalee Muslim" is generally regarded as a "living oxymoron," and the Bangalee Muslims are considered to be perennially trapped in a dilemma of identity over their Bangaleeness and Muslimness. The extraterritorial pull of religion often confounds their regional interests. How did AK Fazlul Huq, one of the most prominent Bangalee Muslims of the 20th century, deal with the dilemma? This article is an attempt to find the answer through a brief study of his life and works.

At the beginning of the 20th century, when Fazlul Huq joined politics, the Muslim political scene was dominated by elites—i.e. nawabs and zamindars. He himself was initiated into politics by ashraf Muslims like Nawab Salimullah and Nawab Ali Chowdhury. He actively participated in the founding of the All India Muslim League in Dhaka on December 30, 1906.

Fazlul Huq, like Salimullah and Nawab Ali, had the conviction that unless there was development of education, the Muslim community would remain backward and weak, and would continue to be exploited by the more advanced communities. Therefore, he put all his effort into the advancement of Muslim education and increasing their presence in civil services.

Fazlul Huq was closely associated with all the plans and schemes for the establishment of Dhaka University, which was an imperial concession to the Muslims of East Bengal following the annulment of the first partition of Bengal. He, with the help of Sir Abdur Rahim, obtained from the government a recurring grant of 550,000 rupees, and therefore the university no longer had to beg for money every year to the government of Bengal.

During the non-cooperation movement, launched on September 4, 1920 by Mahatma Gandhi, Fazlul Huq supported the Congress's programme of boycotting British goods and titles, but he was against the idea of boycotting schools and colleges. He felt that such a move would seriously hamper the progress of the Muslim community; therefore, he left Congress.

Similarly, Fazlul Huq was very vocal about the persistent discrimination in appointment of Muslims in government services. In his testimony to the Royal Commission on the Public Services in India (1914), for example, he said, "In considering what would be a due representation of a particular community, regard should be had to its numerical strength in the province, to past history and political importance generally. In Bengal, for instance, Muhammadans (Muslims) should be given at least half the appointments every year."

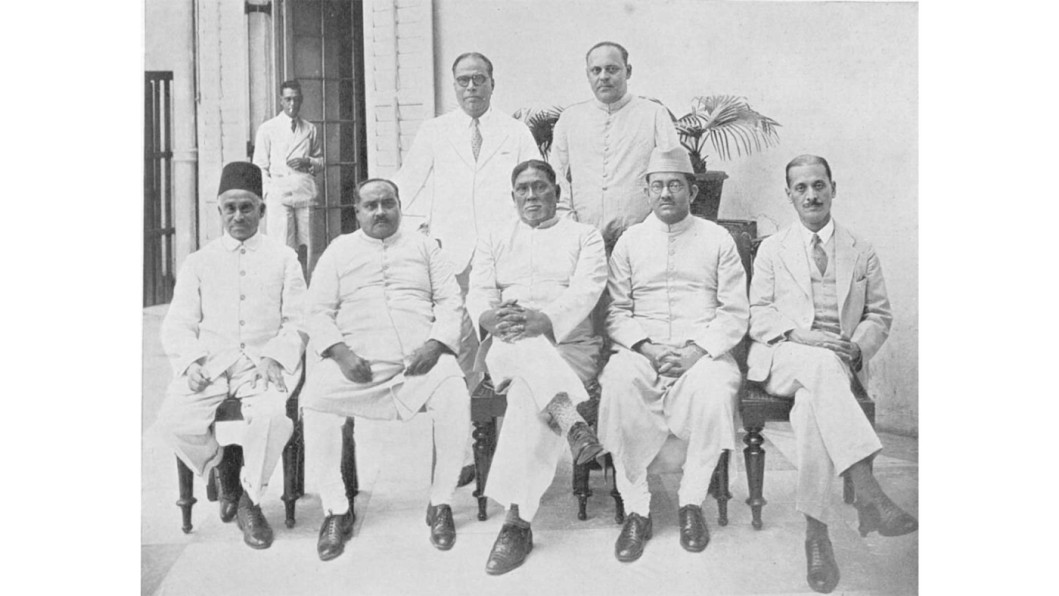

Politician and author Kamruddin Ahmad stated that the Fazlul Huq government (1937) in Bengal "for the first time opened avenues of employment [for] the educated middle-class Muslim young men."

Thus, gradually, Fazlul Huq became the spokesman, respectfully called Huq Saheb, of the emerging educated Muslim middle class of Bengal. To the poor and starving peasants of Bengal, the majority of which happened to be Muslim, he was, according to politician and author Abul Mansur Ahmad, also the messiah of their daal-bhat.

Fazlul Huq founded the Krishak Praja Party (KPP), which started a mass movement with the objectives of establishing peasant rights, relieving the peasants of the oppressions of moneylenders and zamindars, and making raiyats the owners of land by abolishing the zamindari system (langol jar jomi tar). Historian Tariq Omar Ali opines, "Fazlul Huq's peasant populist election campaign, particularly his fiery oratory, were critical in shaping this emergent Bengali Muslim peasant community into a political force."

Most of the zamindars in East Bengal were Hindu, and therefore, there were attempts to portray KPP's political programmes as communal. But this does not hold true as Huq's KPP was a fierce opponent of the Muslim League, which was committed to the strategy of communal separatism in politics, and was dominated by feudal and capitalist interest groups like Dhaka nawabs and the Ispahanis.

The 1937 Patuakhali election is a case in point. KPP's Fazlul Huq versus Muslim League's Khwaja Nazimuddin. The champion of Bangalee peasantry versus the scion of the Muslim elite, landed aristocracy of Bengal. Muslim League unashamedly played the religion card to attract Muslim voters. The Muslim League's mouthpiece, The Star of India, wrote, "A vote for the Muslim League means a vote for united Islam." The League ran vicious campaigns against Fazlul Huq, portraying him as a stooge of Hindu-dominated Congress. Huq's KPP reproached the League's campaign for Muslim solidarity as a "false cry" and adopted a non-communal programme highlighting peasants' interest regardless of religious beliefs. Fazlul Huq came out victorious in this "fourth battle of Panipat"—as termed by BD Habibullah—receiving 70 percent of the vote.

Fazlul didn't limit himself to Bengal politics. He played an instrumental role in formulating the famous Lucknow Pact (1916), which was seen as a beacon of hope to All Indian Hindu-Muslim unity. He was the president of the All India Muslim League from 1916 to 1921. He also held the position of general secretary of the Indian National Congress from 1918 to 1919.

However, Fazlul Huq never completely merged his Bengal politics in all-India concerns that were often detrimental to the interest of the region. Abul Mansur Ahmad testified that Muslim League's callous indifference to the annulment of the Muslim-dominated province of East Bengal and Assam, and its agreement in the Lucknow Pact to the permanent reduction of the Muslims of Bengal to a minority, in exchange for weightage of a few Muslims seats in other provinces, disillusioned Huq about the party. "It must have pained Fazlul Huq that all-India Muslim leadership did not raise its little finger of protest when Deshbandu's Bengal Pact was turned down by (the) Indian Congress during his life time, and rescinded by the Bengal Congress after his death," Ahmad added.

In the declaration of the Lahore Resolution (1940), Fazlul Huq's emphasis on "independent states' shows that he was not acquiescent to a singular Muslim solidarity. Rather, it was a forceful statement in favour of provincial autonomy.

In 1943, Fazlul Huq wanted to form a national government in Bengal with representatives from all the parties, including the Muslim League, Congress and Hindu Mahasabha. However, due to Jinnah's opposition, this couldn't happen. Politician and author Abul Hashim opined that if this plan had been executed, the partition of Bengal could have been prevented. Even in the twilight of his political career, Fazlul Huq was illegally dismissed from the chief ministership of East Bengal (1954) by the Pakistani authority for expressing his desire for the unity and autonomy of Bengal.

Fazlul Huq was also the patron saint of Bangla language and literature. In 1937, at the Lucknow session of the All India Muslim League, some non-Bangalee leaders proposed adoption of Urdu as the official language of the party. The Bangalee delegates under the leadership of Fazlul Huq vehemently opposed this move, and the resolution was dropped. He was also an active supporter of the 1952 Language Movement. The election manifesto of the United Front, which Fazlul Huq led to victory, called for recognition of Bangla as a state language, transformation of the then official residence (Burdwan House) of the chief minister of East Bengal into Bangla Academy, construction of Shaheed Minar at the site of the police firing in 1952, and declaration of February 21 as a public holiday.

In light of the above discussion, the political career of Fazlul Huq can be summarised as follows: at the all-India level, Fazlul Huq fought for the regional interest of Bengal, and in the parley of Bengal politics, he fought for securing the rights of Muslims, particularly the Muslim peasants and educated Muslim middle class. His fight for his co-religionists never descended into communalism.

Historian Sana Aiyar rightly points out that Fazlul Huq refused to prioritise the Muslim identity over the Bangalee identity. The distinguished aspect of his politics, according to Aiyar, was the reconciliation of religious and regional identities into one political framework.

I want to conclude this article with the observation of the scientist and philosopher Acharya Sir Prafulla Chandra Ray about Fazlul Huq: Fazlul Huq combined in himself a true Muslim and a true Bangalee, and thus constituted the ideal Bangalee of the future.

Shamsuddoza Sajen is a journalist and researcher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments