How to avoid buying LNG from the spot market

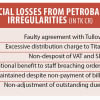

We have known for a while that dependence on the expensive liquefied natural gas (LNG) would put Bangladesh under major financial stress. Four years after LNG was introduced to the local gas supply chain, Bangladesh Oil, Gas and Mineral Corporation (Petrobangla) feels the pinch more than anyone. Meeting the mounting LNG import bill, Petrobangla has apparently exhausted its financial basket and asked the government for help in the form of a major subsidy. It got only a fraction of what it wanted. So it turned to the banks for loans. It even took money from the gas development fund (GDF), which was created exclusively for exploration and development of local gas resources, with contributions from ordinary consumers subscribing to the pipeline gas supply.

How expensive is LNG in the present international market? Bangladesh supplies about 3,100 mmcfd (million cubic feet per day) to the national gas grid. Out of this total gas supply, according to Petrobangla, about 75 percent comes from the local gas fields, which costs an estimated Tk 20,000 crore per year, including tax and other expenses. The remaining 25 percent is imported as LNG from the international market, for which the cost is estimated at Tk 44,000 crore.

Bangladesh buys and procures LNG from two sources: i) Qatar and Oman under long-term contracts at a price agreed upon in the contract – e.g. about USD 11 per mmbtu (million British thermal unit); and ii) The spot market at a fluctuating price. The LNG price in the spot market is volatile and jumps up or down depending on the market situation. At one point early this year, Bangladesh bought LNG from the spot market at USD 35 per unit. So, the prices of gas consumed in Bangladesh compare as follows: USD 2 per unit for locally produced gas to USD 11 per unit for LNG imported under long-term contracts and up to USD 36 per unit for LNG imported from the spot market.

From the above it appears that the spot market price of LNG makes a big difference when accounting for the LNG import bills. This is in spite of the fact that the volume of LNG procured from the spot market comprises the smaller part of the imports – e.g. 150-200 mmcfd out of the total volume of 800 mmcfd. So one way to reduce the financial burden of LNG import is to avoid buying it from the spot market and procure it more under long-term contracts. But that is not possible at the moment because of the lack of contract opportunities. A more immediate option of avoiding spot LNG purchase is to procure gas from the local sources. Bangladesh can very well add to its gas production the volume equal or even more than the amount of LNG bought from the spot market. There are several means to do so, such as:

1. Extracting stranded gas: There are several places where gas reserves have been discovered but remain untouched. This gas is unnecessarily stranded due to the absence of simple measures. For example, the Bhola North gas field, discovered in 2018 with substantial reserves, has not gone into production yet. Bhola is an island district, detached from mainland Bangladesh by a short channel. It is shocking that a simple pipeline connecting Bhola to the mainland was not built to add the gas to the national grid at a time when gas feed from imported LNG is draining crores of taka out of our pockets. This gas field can produce about 60 mmcfd, per a conservative estimate.

Furthermore, a second gas field in Bhola, Shahbazpur, produces less than half of its capacity due to the absence of a pipeline. Zakiganj gas field, discovered in 2021, is yet another unused gas field that can be brought under production immediately.

2. Work over the old wells: Another way of increasing gas production in Bangladesh is to "work over" the old and abandoned gas wells. Many production wells are abandoned as they appear to be exhausted or have some technical issues. At a later time, these wells can be reactivated by further examination and intervention (technically known as workover). Workover is a normal procedure in the gas production system and has seen successes in the recent past, like the one in Kailashtila 7 well, which was revived to produce more than 15 mmcfd gas several years after it was abandoned.

3. Enhancing production rate per well: The international oil companies (IOCs) working in Bangladesh have their gas wells producing 40-70 mmcfd per well. The production rate by the national gas companies (Bapex, FGFCL, SGFCL), on the other hand, ranges from less than 10 to 30 mmcfd per well. Studies carried out by consultants have pointedly suggested that gas production in many of the locally operated wells can be increased by taking several simple measures, like replacing the smaller production tubes with larger ones, for example. Workover of more and more old wells is a realistic way to increase gas supply immediately from local sources.

From the above, it is evident that there are practical ways for the government to avoid procuring LNG from the very expensive spot market. At the same time, it should find more agencies that would enter long-term contracts to provide LNG at favourable prices to Bangladesh. In the long run, though, there is no alternative to extensive gas exploration, should Bangladesh want to tackle the gas crunch.

Dr Badrul Imam is a former professor at the Department of Geology of Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments