A pluralism that transcended the sectarian divide

"Musalmane bole go Allah, Hindu bole Hari

Nidankale jabe re bhai eki pothe choli"

(Muslims say Allah, Hindus say Hari

In the end, we all travel the same path.)

— Bengali folk song

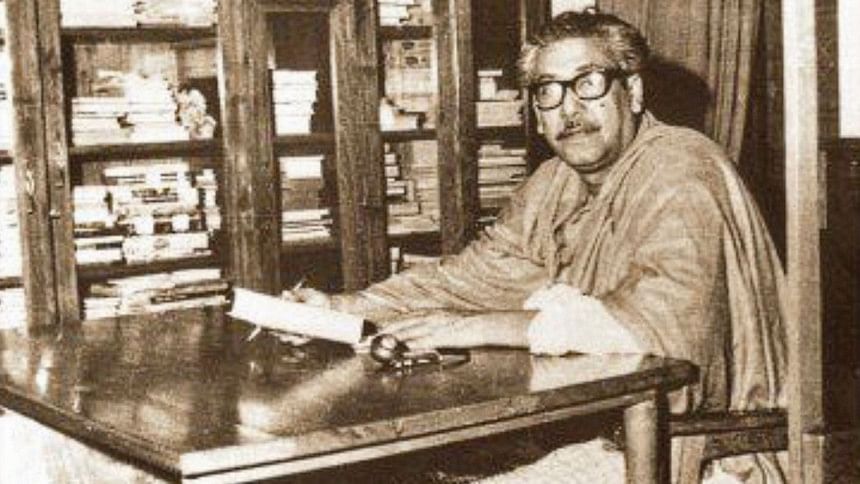

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is rightly celebrated for leading the people of Bangladesh to independence after a prolonged, decades-long struggle that required acute political acumen, a remarkable capacity to win the hearts of his people, and most important of all, that rare sort of courage that had the power to stare squarely into the eyes of death.

There is no gainsaying the fact that he had it all.

However, for me, there is something very special about Bangabandhu that singles him out among the world's statesmen who have led their people to freedom.

It is his transcendent humanism that makes Bangabandhu so exemplary and relevant in this fraught contemporary age.

It is our ill fate to live in an age of vicious sectarian schisms. We live today in a world where a rogues' gallery of unscrupulous political hucksters are exploiting hatred. Many parts of the world are plagued by a majoritarianism driven by a fearsome prejudice of a privileged majority. It is all the more dangerous because it is powered by a malice spurred by an erroneous sense of victimhood by the majority/powerful who cast a jaundiced eye at minorities.

In our subcontinent, Hindu-Muslim antagonism has bedevilled our polity for a long time. One of its terrible manifestations was the bloody partition of India in 1947. It is a bitter irony of partition that the biggest claim of its supporters also proved to be one of the most hollow. Instead of resolving the problems of minorities, Pakistan, the safe haven for aggrieved Muslims in India, compounded it. Now you had two nations whose minorities felt insecure—Muslims in India and Hindus in Pakistan—and the enmity between the two nations exacerbated that insecurity.

From 1947 to 1971, as the Bengalis of erstwhile East Pakistan fashioned a new identity, sectarian prejudice (read anti-Hindu prejudice in East Bengal) was a potent tool used by the Pakistanis and their Bengali sympathisers who tried to nip a growing humane, inclusive Bengali consciousness.

It had a seductive appeal. The nascent Bengali community of East Bengal, predominantly Muslim, was susceptible to prejudice. Painful memories of socio-economic oppression by the Hindu elite in the pre-partition era were deliberately stoked to incite it.

Thank goodness, the people of East Bengal balked. The Awami Muslim League dropped the "Muslim" from its name in the 1950s. And nowhere was this refusal to bow to sectarian prejudice better epitomised than in Bangabandhu's wondrously unshakeable commitment to pluralism throughout his entire career.

Bangabandhu and the Awami League remained steadfast in a Bengali identity that was open to all, regardless of faith, which embraced an ethos that celebrated Rabindranath and Nazrul in equal measure.

How different he is from many of today's political movers and shakers! I sometimes wonder which is worse, the outright political rogues who shamelessly exploit bigotry, or the more mainstream politicians who know better but nonetheless play footsie with prejudice out of political expediency.

After the creation of East Pakistan, a secular Bengali consciousness blossomed among the predominantly Muslim Bengalis of erstwhile East Pakistan.

It had two separate roots. One was more intellectual. I would argue that the nascent Bengali intelligentsia shaped by the University of Dhaka played a pivotal role in developing a rationalist, humane identity that was linguistic and cultural, rather than religious.

Bangabandhu's pluralism was more deeply rooted in the heart of Bangladesh, its rural hinterland. It came from the more traditional syncretic traditions of rural Muslims and Hindus, informed by values that embraced a humanist interpretation of religion that shirked orthodoxy. Bangabandhu's secular, humane values, I would argue, did not spring from the intellect, but from the heart. That is the reason it struck such a deep chord with Bangladeshis from all walks of life. This is the humanism that is not from the academe but from grassroots spiritual humanist traditions. It is a humanism that draws its inspiration from the likes of Lalon Fakir, Hason Raja and Shah Abdul Karim.

I think we often err when we infer that orthodoxy and intolerance are the handmaidens of deep faith. Bangabandhu and Pakistan's founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah present a telling corrective. Jinnah drank whisky, loved his ham sandwiches and married a Parsi woman. He had the lifestyle of a pukkah Sahib. Yet his political credo centred around the dubious but implacable contention that Hindus and Muslims were two different nations. Bangabandhu was a practicing Muslim, yet he believed in a Bengali identity that warmly welcomed people of all faiths.

The true test of a statesman is not a professed commitment to an inclusive, plural identity that embraces people of diverse faiths, but his ability to stand steadfast even at the risk of losing political capital when battling the siren call of opponents who are happy to exploit sectarian prejudice.

Bangabandhu, let it be said, passed that test with flying colours.

And what of us, heirs to his glorious legacy?

I do not think we can say in all honesty that we have done a satisfactory job of upholding Bangabandhu's humanism. Occasional outbursts in social media reveal the dark underbelly of our society. The flurry of outrageous bigoted remarks against cricketer Liton Das and actor Chanchal Chowdhury in the recent past, for example, are a stark reminder that the Sisyphean struggle to establish plural, humanist and inclusive values is still a work in progress.

Ashfaque Swapan is an Atlanta-based writer. "Mujib Hatya Chakranta", his Bangla translation of Lawrence Lipschitz and Kai Bird's investigative report on the murder of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, is available on Kindle.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments