Is monetary policy helping contain inflation?

The Federal Reserve of the US and the European Central Bank kept hiking policy rates in their fight against record inflation throughout last year and this year whereas the central bank of Bangladesh chose not to use the full force of the monetary policy.

The country's efforts aimed at curbing higher inflation did not succeed largely because of a 9 percent interest rate ceiling that the Bangladesh Bank introduced in April 2020.

This was because the cap largely made the policy rate hikes put in place by the central bank ineffective as it contributed to the flow of cheap money in the economy, thus pushing up the inflation rate.

When Abdur Rouf Talukder joined the BB as its governor in July last year, inflation stood at 7.48 percent. And in his maiden press conference a month later, he backed the cap.

He said withdrawing the ceiling to control inflation is the "textbook solution" and there is no need to follow the US since Bangladesh did the best among the South Asian countries to tackle the pandemic-induced crisis by following its own methods.

But western economies have shown that a tighter monetary policy works when it comes to curbing inflation.

The US has raised interest rates to the highest level in 22 years to stabilise prices and make borrowing costlier. It has raised the rate 11 times since early 2022.

As a result, annual inflation in the world's largest economy is expected to have reached 3.6 percent in August. It would be much lower than the June 2022's peak of 9.1 percent.

Similarly, eurozone inflation halved from an all-time high of 10.6 percent in October last year to 5.3 percent in August this year.

The BB has not been much behind the rest of the world in raising policy rates.

It started to increase the repo rate in May last year as inflation went up following a sharp increase in the commodity prices driven by the crisis brought on by the Russia-Ukraine war. The rate has been revised upwards five times since then.

But the rate hikes did not bring expected results as funds were still cheaper owing to the interest rate ceiling.

Finally, in June this year, the central bank's monetary policy for July-December withdrew the cap and introduced a market-based lending rate to meet conditions attached to the International Monetary Fund's $4.5 billion loan.

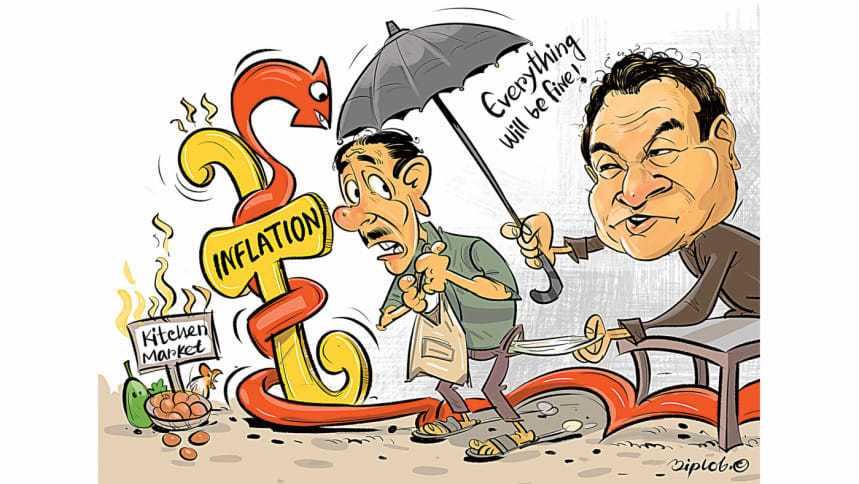

But higher inflation has already brought about a cost-of-living crisis in the country.

Average inflation rose 23 basis points to a 12-year high of 9.92 percent in August against the central bank's full fiscal year target of 6 percent. In July, it stood at 9.2 percent.

In the past one year, experts squarely blamed the 'faulty' monetary policy for the runway consumer prices.

"Bangladesh has failed to control inflation because it did not use the monetary policy," said Fahmida Khatun, executive director of the Centre for Policy Dialogue.

She explains that when inflation rises persistently and goes past the target, central banks usually take cautious measures through monetary policies to control the money flow.

"But in Bangladesh, the money was very cheap until June due to the interest rate cap. The lending rate was lower than the inflation rate and this increased the money supply."

Fahmida said the central bank lifted the interest rate cap but it was too late.

The broad money, a measure of the money supply in an economy, recorded a 10.48 percent year-on-year growth at the end of June.

Mustafa K Mujeri, executive director of the Institute for Inclusive Finance and Development, said the central bank framed monetary policies until June without bringing flexibility to interest rates on loans.

"There is a lack of proper policy since we didn't follow the market-based interest rate and the exchange rate."

The former chief economist of the BB also blamed the lax supervision in the commodity market and in the money market.

"The unnecessary volatility in our commodities market has increased the prices of a number of goods and this has hurt the pockets of consumers."

Mujeri cited the example of Sri Lanka and India for the proper management of inflation.

Sri Lanka was facing the worst economic crisis in its history just a year ago and inflation rocketed to 69.8 percent in September.

In July, inflation in the Island nation stood at 6.3 percent, also way lower than 12 percent in June.

Inflation eased in India as well.

Selim Raihan, executive director of the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling, said the government has yet to take effective measures to control higher inflation.

"Several countries succeeded in reining inflation by hiking the interest rate, but we have not employed our monetary tools to take the right steps."

Market factors also responsible

Fahmida said a faulty market management was another reason for the skyrocketing inflation.

"There are some sections that are creating an artificial shortage of products."

The noted economist said the argument that Bangladesh's inflation is import-based is not fully correct.

Inflation was supposed to decline in Bangladesh since the price of commodities has come down in the international market in recent months.

"Instead, inflation shows no sign of slowing down," she said.

On Sunday, Rizwanul Islam, a former special adviser of the International Labour Office in Geneva, said market imperfections and foul play in a monopolistic/oligopolistic market have long been pointed out as a major factor behind the recent inflation.

"It's a pity that very little is being done to moderate this monstrous shock."

He thinks given the nature of the current inflation, conventional instruments like monetary policy alone can't fight it.

"Other measures, especially to ease and regulate the supply of essentials, are urgently needed."

In June, the central bank blamed several factors for the elevated domestic commodity prices and inflation. They include higher prices of imported items in the global market, a larger depreciation of the taka, and the upward adjustments in fuel and energy prices.

The taka has lost its value by about 27 percent against the American greenback since the outbreak of the war in February last year.

A lack of a competitive environment, along with market syndication, could have also contributed to the current CPI (Consumer Price Index) inflation, the BB said.

Yesterday, BB Chief Economist Md Habibur Rahman said the central bank has taken a series of measures, including the withdrawal of the interest rate cap, and the hike in the policy rate, in order to tame inflation.

"It will take time to tame higher inflation."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments