Dark Academia: Why we love it and what needs to change

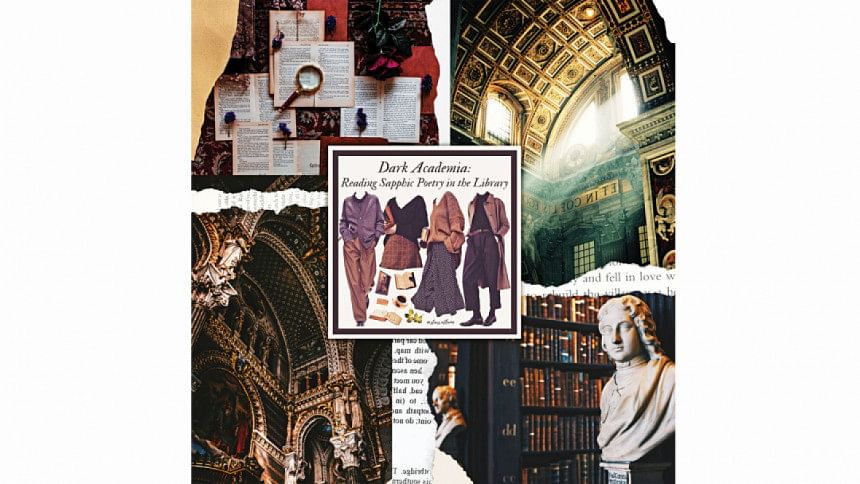

Dusty libraries, tweed blazers, candles, classics, coffee pots and armchairs: these are some of the basic elements of a social media aesthetic when one is into Dark Academia. The rising popularity of Dark Academia, which essentially romanticizes an intellectual lifestyle and classic literature, has turned into more than just a facet of contemporary literature and culture. It has evolved into a prominent subculture and even a lifestyle choice for a niche audience.

Books considered to be part of the Dark Academia (DA) sub-genre are usually set in an academic establishment, be it a boarding school or a liberal arts college, illustrated by a darkly poetic atmosphere, often with the backdrop of sinister, gothic architecture. Books like Leigh Bardugo's Ninth House (Flatiron Books, 2019) and Victoria Lee's A Lesson In Vengeance (Delacorte Press, 2021) outline this especially well. Characters belonging to the genre usually have a profound passion for seeking knowledge. Dwelling in existential dread, their diction is dominated by classical prose. Surrounding the brooding, morally-grey characters are common themes of murder, secret cults, and queer angst in these books.

In today's late capitalist era, where everyone is dependent on modern technology, DA has risen as a countercultural response. While pop culture often satirises individuals with a thirst for knowledge as "nerds", DA-enthusiasts find embracing "the dark academia lifestyle" comforting and relatable. It allows them to vicariously live through a privileged academic life with a perforating access to knowledge.

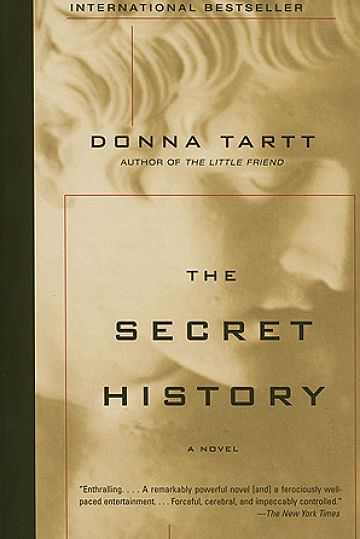

Mary Shelly's Frankenstein (1818) and Oscar Wilde's The Picture Of Dorian Gray (1890) may be thought of as the bibles of Dark Academia, but it was Donna Tartt's The Secret History (Vintage, 1992) that became the modern cornerstone of the sub-genre. Tartt's debut novel had all the key tropes to appeal to a new generation of readers who enjoyed fantasizing about life on campus, about learning an ancient language and solving mysteries. But, like most other genres, Dark Academia, too, is disproportionately eurocentric.

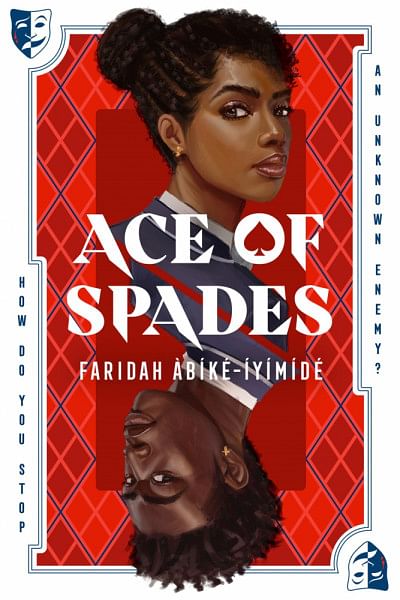

Earlier books of the sub-genre, like Maurice (1971) by EM Forster or Dead Poets Society (1989) by Nancy H Kleinbaum, all glorify western culture. It is only recently that the landscape has been including and publishing authors of different ethnicities. Naomi Novik's Scholomance series (2020), for instance, has the most diverse characters among contemporary DA. Ace Of Spades (Macmillan, 2021) by Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé also offers remarkable critique of the traditional elements of DA, as it challenges the existing racism and classism of academic establishments in the western world. In the book, Chiamaka and Devon, the only two Black students in an all-white school, find themselves in an old system of social eugenics where Caucasian students and teachers try to sabotage their pursuits and have them thrown out.

These narratives, however, still promote the toxic prejudice of western educational systems, which establish the prominence of characters belonging to a predominantly white, bourgeoisie class. Apart from this, the DA culture also highlights unhealthy behaviour and problematic habits such as alcoholism, intake of morbid amounts of caffeine as sustenance, romanticising mental health problems, and even glorifying suicide.

The mystifying beauty of DA culture lies in the romanticisation of the mundane; there is something poetically sinister about the way these books represent something as basic as academia, which is alluring to the younger generation of readers. Perhaps it is the idealised aesthetics that draw them in. But how politically justifiable is the non-critical consumption of this sub-genre?

In reality, educational institutions have always maintained a certain level of racist and classist hierarchy and it is concerning that the Dark Academia aesthetic and its most prominent books only perpetuate such discriminating practices. I believe that as readers, we should be wary of any toxicity that pop culture propagates. We must not forget that Dark Academia should be a critique of the system rather than perpetuating the very conventionalism against which literary criticism stands.

Nawshin Flora is currently daydreaming about catching up to her never ending TBR list. Remind her to get enough sleep at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments