Himu taught me it was okay to not be normal

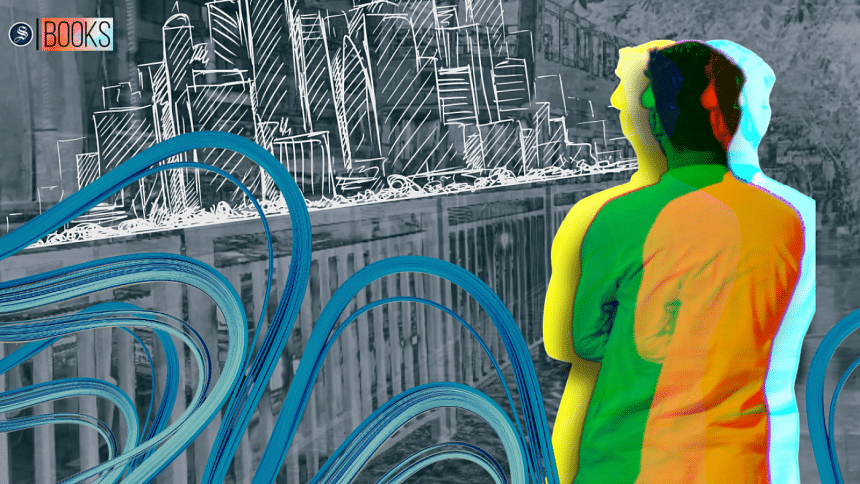

Untidy fringes of hair on his forehead, a simple yellow panjabi with no pockets, and a mind full filled with never-ending curiosity—this is how Humayun Ahmed's Himaloy appears to us while he takes midnight strolls around Elephant Road, through Shahbagh signal on moonlit nights, relishing the beaming yet soothing rays of the far, far away moon.

I was introduced to Himu while mimicking my Nana. I would sit on his arm chair, wear his golden framed specs and get lost in pages of the books. This was the prime aim of my life—the signature attribution of adulthood in my young mind.

As soon as I turned 12, Nana brought me a copy of Parapar (Anyaprokash Books, 2005) and I instantly fell in love with Himu, his unconventional questions, and the way he perceived the world around him.

With time, his choice of actions came to me as a revelation, often challenging the ways I grew up thinking of what counted as "normal".

The way Himu ridiculed social stigma, especially criticising capitalism and the norms set by "pseudo" Marxists, was not something I was used to, as I was always taught to be competitive from a very early age.

Himu not only made me look beyond goals that lead to a luxury of life, but he also taught me to enjoy the tiny bits that make life agreeable. His choice of friends compelled me to think at least once of how we often fail to pick the right one just because we are too blinded by our prejudiced perceptions and end up judging the actor instead of the action.

Himu introduced me to a new world of emotions where people were allowed to make mistakes, be mischievous, and not be judged for it. Harnessing one's internal emotions and external expressions is something Himu never succumbs to, despite the world trying to teach him his ways on numerous occasions. The way he repels such 'set' norms and sometimes even urges his inner cravings to leave his side while he walks the path his father had chosen for him years ago, are commendable.

Many argue that Himu behaves in such a manner due to the effect of a childhood trauma he went through when his father murdered his mother, only for the sake of bringing him up as a "great man" who rejects materialistic needs and capitalistic wants.

However, there is no denying that the way he normalises poverty and low standards of living is inspiring, especially for those who, after a long and tiring day at work, sleep in comfort with dreams of a better life serving as their lullaby. For Himu, finding happiness is easier said than done—a phenomenon which is thought to be absurd by most.

I find his perception regarding the nuances of life not just enlightening but also acceptable, subtle, and delightful.

To add to this, Humayun Ahmed's descriptions are vivid, especially while penning incidents in which Himu appears to be witty and calm. But they are no less impactful when he makes the point he intends to, when delivering food for thought.

While I spend hours worrying about how to meet my ends financially, Himu, who has no source of income, happily substitutes his transportation costs with the healthier option—walking—and he never worries about groceries in his kitchen cabinet. This comes to me as a ray of hope.

With every passing day, as I scroll through my newsfeed looking at people crying over their inflation and pandemic-hit life, Himu, the son of a psychopath who seldom opts for rationality, instils light in my sadness.

With most of my friends judging me over my obsession with Himu, and me discarding their logic behind how Himu is merely a character fit for children, I find if we could accept more Himu's, life would probably become a lot easier.

I firmly believe that resilience is essential to surviving in today's world. The first person to teach me to adapt and proceed with whatever I have instead of complaining about things I don't, was Himu—a crazy night dweller, too unique to be accepted by the "civil" society.

Ashley Shoptorshi Samaddar is a Sub editor at The Daily Star's News Desk.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments