Literature or sadism: The bleak picture of trauma in ‘A Little Life’

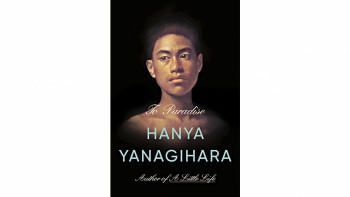

There are few novelists as cruel as Hanya Yanagihara—and in A Little Life (Doubleday, 2015), her pen draws blood. Nine years on, the controversy of the 800-page character study of an irreparably broken protagonist is still ablaze with accusations that it sadistically exploits trauma for profit.

A Little Life begins deceitfully enough, with four friends moving to New York after graduating university but as it tracks their lives for the next several decades, Jude St. Francis emerges as the black-hole centre of the story. At first, Jude is reserved and distant, a darkness amidst the friend group's cosmic kaleidoscope of buzzing parties, dingy apartments, and bloodthirsty ambition. An enigma who divulges nothing, his friends know nothing about him, not even his ethnicity or how he really got the injury which frequently debilitates his legs.

But soon, with a growing ferocity, the reader is pulled into a horrific truth about Jude. Marred by an inconceivable childhood trauma that is he is unable to process, let alone confess or heal from, Jude sinks deeper into disturbing self-harm and self-hatred over the decades.

Yanagihara, a former Condé Nast Traveler editor, is a travel writer. She trades in storytelling that is so richly descriptive that the reader is transported to the deepest, darkest depths of Jude's mind.

Jude's character is written in such excruciating detail that you can practically feel him bleeding into the ink on the page; your own head echoes each self-loathing thought, every twisted conclusion. You sit powerlessly beside him on the bathroom floor as he slashes his own skin; you are locked in the room with his monstrous abusers as he relives childhood trauma.

The intense connection that Yanagihara successfully creates between Jude and the reader is a rare literary feat. Written almost completely in third person, the reader does not become Jude but becomes someone who deeply cares and worries for him. And it is precisely this written excellence that earns A Little Life its controversy. At what point is writing so expressive, so raw, that it makes a dangerous spectacle of human suffering?

Equipped with a powerful reader-protagonist union, Yanagihara plays a cruel game. She dangles the hope of Jude's recovery temptingly, only to snatch it away each time.

In the end, nothing will save Jude—not success, money, friendship, romance, not even parental love. He will fear those who love him unconditionally and will never believe he is worthy of genuine human connection. Being adopted at age 30 will not console the pain of being an orphan and the terrifying power he commands as an eminent lawyer has no strength against the demons at home.

Of course, I would've liked it better if the book ended just one chapter earlier, but literature is more than fan service, and Yanagihara intended, for better or for worse, to elicit the reader's misery. A happy ending would have meant closing the book with a satisfied smile; it would not have left the reader with a mass of emptiness and pure anger for how Jude's life turned out. That is why she not only wrote an 'unfixable' character but did so with brute maximalism.

Make no mistake, however, of reducing Yanagihara's graphic writing to mere profit-seeking. Different literary representations of trauma, no matter how ugly or painful, are important. As philosophy professor Eliss Marder puts it, literature is how we communicate aspects of the human experience that exceed ordinary expression and may even exceed human understanding. Similarly, Cathy Caruth, a pioneer in trauma theory, has long considered literature a vehicle for witnessing what cannot be completely known. We cannot reject pain from public comprehension because it is difficult to stomach. For some, trauma is not a backstory from which they can turn away. For some, the world is relentless, unforgiving, and there is no greater purpose nicely weaved throughout to make it all worthwhile.

A Little Life is a tormenting read, but it is so much more than its brutality. Between the lines, Yanagihara sketches an exquisite portrait of human compassion and empathy. She writes most strikingly of friendship as unconditional love, selflessness, chosen family, and a deeply transformative human connection. Undoubtedly, Jude encounters vicious adversaries throughout his life that permanently scar him but the friendship he finds is exceptional. The fact that it still could not completely "save" him does not change the love and compassion he found in so many.

There is a reason why several chapters are invested for the development of secondary characters, and why the only time Yanagihara employs a first-person perspective is from someone who loved Jude unconditionally. These characters' humanity rises above all and their stories regale the reader with a subtle warmth unlike any other: friends and readers alike end up considering it a privilege to help carry any part of Jude's burden he allows, even when it is extremely taxing.

Much like A Little Life shows, all-consuming connection is not healthy, but it is profoundly human.

Alifa Monjur is studying commerce and law in Sydney.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments