On ‘Gaza Monologues, the Land of Sad Oranges’: A theatrical performance by Prachyanat

How do you attempt to understand testimonies of mass public trauma? "There is an absolute obscenity in the very project of understanding", states Claude Lanzmann, maker of Shoah (1985), a film of Holocaust testimonies. A question as deceptively simple as "Why have the Jews been killed?...reveal[s] right away its obscenity". As part of the audience of Gaza Monologues, the Land of Sad Oranges, a theatrical performance by Prachyanat that ran on January 19, 2024 at La Galerie of Alliance Française de Dhaka, Dhanmondi, I was confronted with an equally obscene question—why are the Palestinians being killed?

My years' worth of book-knowledge failed me as I tried to grapple with this question whilst listening to unthinkable testimonies of trauma written by youngsters who experienced the Gaza war during their adolescence in 2008-2009. Weaving these testimonies into an immersive art form, the theatrical performance submerged me into a realm void of spatiotemporal conventions, where 2008 coincides with the now, and where a Dhanmondi audience, through many, many layers, bears witness to trauma in Gaza. Subsequently, it challenged me to emerge with a creative listening approach to trauma in lieu of an impossible, "obscene" attempt to understand.

One striking testimony recounts the aftermath of witnessing the death of a neighbour during a bomb explosion, the body blown up into shards. Although this incident, in actuality, happened in a second, it seemed to have escaped temporal conventions and, yet, it was reduced to "only 15 minutes of news time." Piled on top is another layer of complexity as the writer's mother, also a witness, has her own, yet much more intensely felt version of the incident that runs for two hours and that "she cannot shut up about." From the reciter of this monologue emanates a quavering voice which resounds an assurance that, if she were alive, she would be telling this "story" to us too; as this voice trails off, another mellifluous voice hums a doleful tune in tandem with the strings of a guitar. However, there is a trace of annoyance in the monologue at the fact that the writer's mother always told the story as if they were not right there beside her, as if they had not witnessed the incident. The testimony then concludes with the writer questioning themselves—had they actually been there? This highlights the unreliability of memory—memory lies, leaves gaps, and fills gaps. Consequently, the transference of trauma through conscious recollection becomes muddied. The testimony thus, resonates with what Cathy Caruth, in her work on trauma and memory writes: "the capacity to remember is also the capacity to elide or distort".

On the other end of the spectrum, trauma that has not been integrated into consciousness, as in with PTSD patients, is paradoxically inaccessible both to the victim and the listener. I say "paradoxically" because this trauma results from an event that, due to its unexpectedness or horror, was not fully experienced as it occurred and, consequently, never became "a narrative memory [like other memories] that is integrated into a completed story of the past." The paradox lies in the fact that, untainted as it is by "memory" or conscious recall, this event retains its precision as it, due to never having been fully experienced, insistently and exactly recurs only in the form of nightmares or undistorted flashbacks that are, again, not fully understood. Thus, another Gaza testimony states, "I hate seeing dreams".

Caruth offers that the "impossibility of a comprehensible story, however, does not necessarily mean the denial of a transmissible truth". In fact, Lanzmann, for his film, began with this very impossibility as he refused the conventional framework of understanding to welcome a "creative act of listening." He thus states, "Not to understand was my iron law during all the eleven years of the production of Shoah. I had clung to this refusal of understanding as the only possible ethical and…operative attitude…There was an absolute discrepancy between the book-knowledge I had acquired and what these people told me. I didn't understand anything anymore". He adds, "This blindness was for me the vital condition of creation". This act of refusal for Caruth then, is a creative "way of gaining access to a knowledge that has not yet attained the form of "narrative memory…" because "[w]hat is created does not grow out of a knowledge already accumulated but, as Lanzmann suggests, is intricately bound up with the act of listening itself". Trying to make sense of such a refusal and "breaking with traditional modes of understanding creates new ways of gaining access to a historical catastrophe for those who attempt to witness it from afar", argues Caruth. Evidently, the listener of the trauma too is confronted with quite a challenge. I ask myself, is trauma being diluted in the process of transference from the victim to the page, from the page to the theatrical reciter, from the reciter to the audience?

Caruth writes, "The attempt to gain access to a traumatic history…is also the project of listening beyond the pathology of individual suffering, to the reality of a history that in its crises can only be perceived in unassimilable forms". And so I too aim to listen beyond the individual. Within the fabric of the monologues that were recited, I could trace a desperate attempt, by these war-stricken people, at a kind of ornamentation of death, manifested in efforts to make their dead selves look as good as possible—as if that is their only hope at agency. A testimony, in fact, read that since their life is a hopeless possibility, they want to look dignified in death.

That is why one testimony in the performance recounts a relative being terrified at the thought of dying by bombardment because, then, all his efforts to look good in death would be in vain as he would explode into a million little pieces—into nothing.

That is why a grandmother is fretting over her lost fake tooth as her family expects imminent death, with smoke billowing through their crumbling home. Her justification—if she lay dead without her fake tooth she would look unattractive, with her secret laid bare to people who found her.

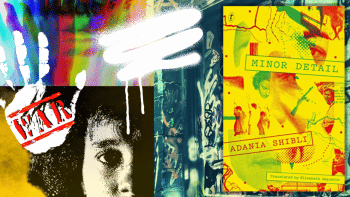

Another testimony talks of their lives as if it were a stroke of luck, in that they consider it an extra to be still living and even more superfluous if they were to ever "outlive" the war or, rather, their "intended destruction"—strongly echoing Marianne Hirsch who uses similar diction to write about Holocaust survivors. Ironically though, the theoretical ideas that I have discussed throughout this essay, including Hirsch's, all stem from a field (trauma and memory) that has consistently disregarded all other forms of trauma, be it from enslavement, colonisation, or the Gaza genocide; and having thus privileged a specific traumatic event (the Holocaust), it has created a narrative of exceptionalism around this event as if other forms of trauma lack gravity. One of the Gaza testimonies stresses the significance of politics and media, declaring that "they are what attacks us and they are what saves us". I would like to add "knowledge-production" to this list of attackers and saviours—it attacks and saves in insidious ways, as exemplified by trauma and memory's skewed making of knowledge.

A stubborn child with a teddy bear does not want to leave it behind whilst fleeing a war-site. The testimony recalls when they used to be happy with this teddy and the reciter of the testimony tears up while she reads, "I don't want to grow up"—the whole audience felt the reciter's passion, the emotion permeated La Galerie, flowed through bodies, leaving a trace of it in each. How do you imagine that being a child's wish? How do you imagine a land where children do not want to grow up and do not want to dream? In lieu of an "obscene" understanding of such impossible questions, the theatrical production by Prachyanat provided its audience an opportunity to engage in an act of creative listening to trauma by presenting it in a multi-layered, fragmented art form.

Momena is an occasional contributor to Star Books and Literature.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments