Motherhood, martyrdom and the spirit of female resistance in 1971

War has a gender. As it tears through cities and homes carrying firearms and riding tanks, littering streets with wreckage and flooding rivers with corpses, we associate war with men. As it births new nations and identities, infusing generations with renewed hope and courage, we associate war with men. Be it guerillas, freedom fighters, intellectuals leading revolutions or politicians designing strategies, generational gender dynamics have placed men at the forefront of war. In the history of Bangladesh's liberation war against Pakistan, men are the protagonists, and while commemorating the three million lives lost in 1971, it is in the honour of the martyred men that the country's streets fill with garlands of marigolds and tuberoses. It is in remembrance of them that songs are composed, monuments are erected and holidays are observed.

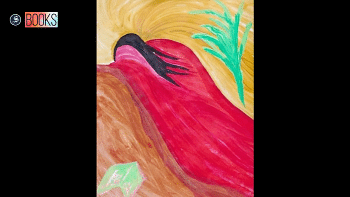

On the other hand, as with other historical events and primarily wars, women's contribution to the 1971 war has been shockingly forgotten or misconstrued and oftentimes, blatantly denied. Women are predominantly remembered as victims of Pakistan's undeniable genocidal rape campaign, which by conservative estimates, claimed 400,000 victims. Bengali women faced severe violation and degradation at the hands of the Pakistani army; however, it was the deafening attention on their shame and assault from both a national and global audience that sidelined and diminished the role of other women in the fight for freedom. Therein lies the power of Jahanara Imam's Ekattorer Dinguli (1986), a poignant memoir which highlights the capacity of female resistance through the author's legacy, losses, and triumphs as a mother, wife, and political activist, over a journey of the months leading to Bangladesh's independence.

At first, Ekattorer Dinguli may seem like the musings of an upper class Bengali housewife, from Jahanara's frustrations at the lethargy of her househelp, to the constant attention her ailing father-in-law requires, to the often humorous temper trials she has to endure as the mother of two headstrong boys. However, we're quickly introduced to the fascinating and exemplary layers that make up Jahanara: her political activism which comes alive through the sheltering and mobilisation of freedom fighters, her social and cultural influence which unites generations across socio-economic groups for the country's independence, and the determination with which she meticulously documents history through her writings. What stays with readers is the force with which she loves and longs for her son, Rumi, an emotion so powerful it cannot be contained within the pages of her book, but spills out onto her readers as they join in her hope and heartbreak, especially in the face of the life-changing sacrifice she needs to make for her country's independence.

Yet, in the instances where women's contribution to war is recognized, it is done so usually in the form of their sacrifices or tolerance. They are almost always at the receiving end of the action, passively reacting (or not reacting) to it.

What is extraordinary about Jahanara Imam's story, and the different roles she undertakes both within her household and in politics, is the ease with which her multidimensionality coexists. Jahanara spends her mornings in the narrow streets of New Market, searching for fresh tilapia, jackfruits and mangoes for her mother's kitchen, while curfewed evenings are spent burying rifles and machine guns in her backyard. Days into the war, her house becomes a secret convergence point for pro-liberation participants, ranging from doctors and journalists to professors and lawyers. Jahanara is seen actively strategizing with them on how to mobilise freedom fighters, collecting and subsequently disseminating these blueprints across her networks. Despite her reservations about her son's participation in the war, from the early days of 1971, Jahanara is seen actively involved in helping Rumi mobilise fighters. Be it by flushing ingredients needed to make explosives, meticulously sewing money into the folds of guerillas' pants, or collecting and transporting necessities like medicine, cigarettes, and money for the battlefield, Jahanara proves that one need not be in the frontlines to fight a war. At the same time, she is seen preparing a menu of shami kabab, biryani, and cha to ensure her guests are well fed.

From a feminist perspective, Ekattorer Dinguli travels gracefully through the decades, translating into a relevant, educational, and crucial account of a woman's fight for her country. At a time when women's rights are severely compromised in Bangladesh, be it through the distressing exploitation of women in the garment industry, or the widespread violation of domestic workers, Imam shows the critical and indispensable role that women play in a country's advancement. Today, her story serves as a plea to those in positions of power in Bangladesh to hold space for women, and enable their mobilisation through equal opportunities and rights.

Perhaps it was the desperation for independence, and an innate survival instinct that expunged conventional gender dynamics and united both men and women in the quest for freedom and a new identity. Or perhaps it was Jahanara's socio-economic background—her being the only woman in an urban, upper class household of progressive men, which naturally propelled her participation in the war. Regardless of her financial and environmental advantages, Jahanara had the option to flee the war, like hundreds had done from within her community, but she chose to remain in Dhaka and actively partake in the country's political movements. Her story serves as a feminist reporter's pad—laying the foundation for how Bengali women can influence socio-political movements, transform a nation's history and shape its future, one that is especially pertinent today as women's voices get silenced, and they struggle to claim their space in light of the country's challenges.

The soul of Ekattorer Dinguli lies in the relationship between Jahanara and her son, Rumi; and in the love, yearning, and heartache that only a mother can feel for her child. Jahanara reaches for her son like she reaches for prayer: in moments of desperation, loss, fear, and chaos, to persuade, implore, reason and beg. The initial months of war take us through her most conflicting dilemma: choosing between her overwhelming love for her first-born and his devastating need to become a freedom fighter. Jahanara is destroyed by the war's dangers and potential outcomes on Rumi, however, his patriotism and relentless zeal for a liberated Bangladesh result in her hesitantly conceding and permitting him to join the Mukti Bahini, ultimately sacrificing her child for the sake of her country.

The endless tragedies within Ekattorer Dinguli, and the heavy and emotionally depleting prose, find respite in the interactions between Rumi and Jahanara. Like a window letting the light in, their exchanges infuse the book with humour, sunny anecdotes, fights over evening snacks and a giddy enthusiasm for a new flag, a new nation. The idyll of their relationship compels readers to participate in their dynamic; Jahanara's family becomes ours, and it immediately makes her personal loss universal.

In August of 1971, Rumi's successful assault on the Pakistan army results in his capture, subsequent disappearance and ultimate death, which remains unknown but largely understood by Jahanara and her family. Her husband, Sharif, and younger son, Jami, are also captured and extensively tortured by the Pakistani military before being ultimately returned. However, the shock of Rumi's arrest and the

lack of information on his whereabouts washes over Jahanara in waves of devastation and helplessness over the months leading to independence.

Despite her anguish and desperation as she searches for her son, while reluctantly accepting the possibility of his death, Jahanara continues participating in the war with sincerity. She dives into finding shelter for wounded fighters, hiding families in her mother's home, and transmitting relevant information across a network of revolutionaries. Rumi's death is an infinite loss, and hangs over her head like a dense, dark cloud; however, what is striking is her relentless courage as she continues to fight in the face of life-changing adversity, especially in the most crucial and precarious months leading to liberation. Unfortunately, Jahanara's reality as a mother is one shared by millions of women in 1971, which demonstrates the scale of Bangladeshi women's sacrifices and contribution to the war, be it as community organisers, messengers, guerilla fighters or martyred mothers and wives.

I first picked up Jahanara Imam's Ekattorer Dinguli at age 15, with apprehension and reluctance as it made its way to my Bangla class' mandatory reading list, unbeknownst to how the book would change my relationship with my country by showing me the forgotten legacy of women's contributions, on whose backs and wombs Bangladesh was made. Over the next 15 years, I came back to the book instinctively, intentionally, and subconsciously, sometimes to understand women, their resilience, courage and capacity to love, but mainly to return home to my mother. As someone whose entire existence is because of and for her mother, Jahanara's every breath, laced with her love and longing for Rumi laid out the blueprint of the lives of mothers, including my own. A love whose power defies all else, and a bond that can only be experienced and hardly explained, Jahanara's complete submission to her son, and utter helplessness in the face of his desires and duties, helped me see mothers for their bravery, their struggles and sacrifices, and unmatched perseverance while weathering losses, and all the love their hearts hold. Often one needs exactly that, a new perspective, a new voice to see what is hiding in plain sight, the gift of a mother's love that is incredibly tempting to take for granted. It was through the magic of her words that I unlearnt and relearnt of the treasures this relationship holds, the inexplicable joy and profound heartbreak of motherhood, and since then have used them to navigate a way back to my first country, my mother.

Ekattorer Dinguli forces one to acknowledge the dire reality of ethnic and religious violence, and the harsh legacy of colonial oppression and divide that has ruptured the fabric of the South Asian subcontinent since 1947, claiming millions of lives, and showing wider and deeper cracks through the years. In the case of Pakistan and Bangladesh, the book reveals Pakistan's prevalent oppression and brutality of the Bangladeshi people, which included among other tyrannies, an attempted erasure of the Bengali language, and its people. Jahanara Imam highlights the viciousness with which divides are perpetuated, and the hunger with which it claims lives within borders and across generations, religions, genders and class. Through her journey as a political activist and her loss as a mother, Ekattorer Dinguli shows that regardless of the outcomes of war, even "winners" straddle both joy and loss, hope and despair, ultimately, leaving no winners in war.

Sarah Rashid, based in New York, is interested in how religion and politics shape art in South Asia.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments