Reading as a form of resistance: Some anecdotes from the 1971 war

It was towards the end of June in 1969, only a few months after the massive uprising that led to the downfall of Ayub Khan's decade-long dictatorship. Historian Ghiyasuddin Ahmad was visiting his friend Anisuzzaman, who was in the midst of packing up his home in Dhaka for a move to Chittagong University. As they chatted in Anisuzzaman's reading room, Ghiyas perused his friend's bookshelf and spotted a copy of Hitler's Mein Kampf. He picked it up and declared, "I will keep it, as it will be of much help to me. You can keep my History of Bengal." Anisuzzaman had borrowed the History of Bengal from Giasuddin a long time ago, but had forgotten to return it.

Professor Anisuzzaman, reflecting on this incident in Amar Ekattor, his memoir of the Liberation War, recalled how many times after Ghiyas's death he had thought of this exchange of books, seeing it as a gift of free Bangla from Ghiyas who had chosen to walk the path of fighting fascists.

Ghiyasuddin Ahmad is one of our martyred intellectuals. He was abducted from his House Tutor's residence at Mohsin Hall by anti-liberation forces on the morning of December 14, 1971. His dead body was recovered 20 days later at the Rayer Bazar slaughter site.

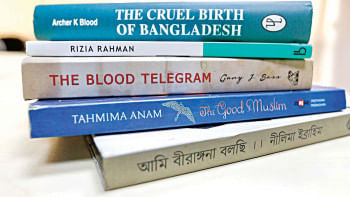

There are many such stories that reveal a lesser-known aspect of Bangladesh's Liberation War—how books fuelled hope and resilience during the War. The seemingly passive act of reading became an active resistance effort in multiple forms, from learning guerrilla tactics to fight the occupying army to finding solace in the history of people living under siege, to keeping up the spirit of freedom. Here are a few anecdotes.

In the first week of May 1971, Muyeedul Hasan was making arrangements to depart for India to join the war effort. One day, Akhtar Ispahani hurried to his residence and gave him Frantz Fanon's Wretched of the Earth, urging him to read the book as it was written in a similar context.

Akhtar was the wife of Isky Ispahani, who belonged to one of Pakistan's 22 wealthiest families.

Upon starting to read the book that night, Muyeedul found it to be incredibly insightful and relevant to the freedom struggle of Bangladesh. As he delved into the text, a question arose in his mind—why would a non-Bengali neighbour risk her life to give him such an important book? Unfortunately, Muyeedul never got the chance to ask her.

Subsequently, Muyeedul Hasan became a special assistant to Tajuddin Ahmad, the Prime Minister of the Bangladesh Government-in-exile, and played an important role during the war.

On May 3, 1971, five weeks into the war, Jahanara Imam noted in her diary that it was her birthday. Her sons, Rumi and Jami, paid her a visit in her room to extend their greetings. They brought no surprise gifts like they usually did. Instead, Jami presented a black rose from their garden, while Rumi gifted her a copy of Leon Uris' Mila 18. This historical fiction was loosely based on the turmoil caused by the Nazi invasion of Poland during World War II, as well as the subsequent resistance.

Rumi gave the book to his mother and said, "By reading this book, Amma, you can regain your mental strength…It has the power to dispel all your fears and help you move on from your grief…If you simply change the names of the country and nation in the book, you will see that it tells the story of Bangladesh, the sorrows of Bangalis, our resistance, and our struggle for life and death."

We learn from Jahanara Imam's war diary titled Ekattorer Dinguli that Rumi had almost all of Leon Uris' books in his personal collection.

It is worth mentioning that the Pakistani junta actively targeted books during the war, banning many works that spoke in favour of the freedom struggle, and burning libraries across the war-torn country.

One of the libraries that suffered this fate was the Raja Ram Mohan Ray Library in Old Dhaka, established in 1871 as the first library in Dhaka. On the night of March 25, the Pakistani Army attacked the library and set up camp there, squandering its rich collection.

Many of the library's books were subsequently sold in lots on the footpaths of besieged Dhaka. After the war, the library authorities placed advertisements requesting people to return any books from the library that they might have in their possession, but the response was poor. The library's hundred-year-old collection was lost forever.

One more story related to Professor Anisuzzaman comes to mind.

During the Liberation War, Indian historian and political activist Gautam Chattopadhyay, along with his wife Manju Devi, devoted themselves to the welfare of Bangladeshi refugees who sought shelter in West Bengal. Gautam also used to visit the training camps of Bangladeshi freedom fighters, providing for their needs and supplying them with essential items, including food and clothing.

Once, when asked about his needs, a young fighter remained silent. Eventually he lowered his head and said, he would appreciate a copy of Jibanananda Das's Ruposhi Bangla. Jibanananda's poetic evocation of Bangla's natural beauty had become a symbol of freedom during the war.

Sharing this incident with Anisuzzaman, Gautam opined that those who possess such love for their country and culture cannot be kept in shackles. History has proven Gautam Chattopadhyay's words to be true.

Shamsuddoza Sajen is a journalist and researcher. He can be contacted at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments