Dolphins washing ashore dead: Fishing nets at fault?

French naval officer, explorer and conservationist Jacques-Yves Cousteau was not wrong when he said, "The happiness of the bee and the dolphin is to exist. For man it is to know that and to wonder at it."

As such it feels especially unfortunate that in this piece, we are having to wonder just the opposite. Why are dolphins washing ashore from the Bay of Bengal, is there one or many more reasons behind their deaths and can anything be done?

News of dead and sometimes emaciated dolphins washing up along the coast have been making the rounds on both social media and news platforms of late.

"If you look closely at the newspaper photographs, you will notice that many of these mammals that wash ashore are emaciated. Often times there's a piece of net around the dolphin's snout," said Rubaiyat Mansur, adviser to the Wildlife Conservation Society Bangladesh programme.

WCS began operations in Bangladesh in 2004 focusing on marine conservation.

Bangladesh Forest Department too believes WCS' statistics and insights on cetacean deaths in our Bay of Bengal are the most accurate as they have kept meticulous data for the past 15 years.

Md Zahangir Alom, country representative of WCS, echoes Rubaiyat Mansur's opinion on dolphin mortalities.

"Dolphins are mammals and like us they drown if they cannot surface to breathe. Most of these deaths are caused by entanglement in fishing nets, particularly in gillnets (locally known as fash/sandi/ilish/sayen/current/poka/bhasa/bhadha/khuta jal) used to catch Hilsa fish," Zahangir says.

"The ban on hilsa fishing ends in June. So from July, when fishers go out to sea again, we start seeing more reports of dolphin deaths," he adds.

This indicates an almost direct relationship between Hilsa fishing and dolphin deaths.

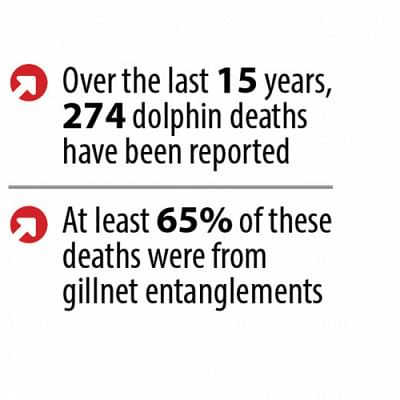

WCS has been keeping count of dolphin mortalities reported in the media or over the WCS dolphin hotline since 2007. Within these nearly 15 years, a total of 274 dead cetaceans have been reported.

"For 130 of these animals, we were able to identify the cause of death," says Zahangir.

"At least 65 percent of these deaths were from gillnet entanglements," he adds. Fisherfolk use gillnets to catch hilsa fish.

According to WCS data, there have been 14 cetacean deaths in 2018, 11 in 2019, 31 in 2020 and 25 deaths in 2021 (from January to August).

For any and all species of dolphins, this many deaths is a cause for concern. According to Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC), a leading international charity that is dedicated to the protection of whales and dolphins, they virtually never have twins; they give birth to one baby at a time every one to six years depending on the species and individuals. The average time between babies for bottlenose dolphin mothers is two to three years.

There might be another reason behind the recent increase in reports of dolphin deaths.

According to Zahangir, there is notably more public awareness, partly due to WCS training programmes for journalists and many educational outreach programmes in coastal areas over the past years. So, there is likely also an increased interest in reporting such incidents.

"There is also more attention towards marine wildlife now, especially since the coronavirus hit and news reports made the rounds saying that dolphins had returned to Cox's Bazar," said Zahangir.

He does not believe that deaths have increased recently, and in fact says dolphins have been dying as incidental by-catch in this manner for a while.

"We need to remind hilsa fishermen before the seasonal ban on hilsa fishing ends and they go off to the sea that they should keep an eye on their fishing nets at all times and safely release any marine wildlife caught in those before they perish."

In terms of solutions and way forward, Elisabeth Fahrni Mansur, senior manager of the WCS Marine Conservation Programme in Bangladesh, believes that we have a shared responsibility in protecting our ocean.

"In terms of government bodies, we're seeing increasing collaborations for marine conservation between the forest department, responsible primarily for protecting wildlife and managing protected areas, and the fisheries department, responsible for managing marine fisheries and marine protected areas," says Elisabeth.

She also said that research conducted in collaboration with coastal fishermen trained as citizen scientists shows that there are, for example, areas where hilsa fishers often catch mostly jatka and that are frequented by dolphins. By identifying high priority and high-risk areas for threatened marine wildlife such as cetaceans, sharks, rays, and marine turtles, it is possible to share ocean space in a way that benefits people and wildlife.

But there is hope. Gillnet fishermen trained in safe release procedures by WCS have documented successful releases of dolphins, turtles, and a whale shark.

Dolphins are protected under the Wildlife (Conservation and Security) Act, 2012, says Deputy Chief Conservator of Forests Jahidul Kabir Jewel. There is a provision for two-years punishment for killing dolphins but it is not a cognisable offence.

"Only the killing of elephants and tigers under Wildlife Conservation Act-2012 is considered a cognisable offence," he added.

The forest official also focused on the need for stewardship at sea to bring an end to this problem and emphasised on collaboration between multiple sectors such as forest department, fisheries department and other relevant bodies.

There is a need to monitor sea-vessels, determine whether they are dumping any chemical waste or otherwise in Bangladesh's waters to also ensure no other unknown reason is contributing to the deaths of dolphins, he added.

Meanwhile, marine conservationist and assistant professor of Zoology Department at Dhaka University, Alifa Bintha Haque, says these deaths are more complicated than meets the eye.

"Without any forensic study on the dolphins that have washed ashore, it is hard to say whether it was a natural death or whether it was due to some other human-induced reasons.

"With that being said, of the dolphins that have washed ashore recently -- some are quite small in size. And it may be the case that these are not natural deaths, but it cannot be said for sure."

And if we look at human-induced causes of deaths, there could be many reasons. "Dolphins, especially the ones that live near the shoreline are especially vulnerable to habitat degradation. The number of mechanised boats has increased as well and dolphins could get injured by a boat propeller, it could also be due to pollution, or due to entanglement in fishing nets or some disease even," Alifa says.

"I really think focus should be given on determining the cause of death by conducting a forensic investigation. This should not be tough as most places where dolphins have washed ashore have a forest department or fisheries office. The forest office could work in collaboration with a veterinary university to conduct the forensic study. That would give some concrete answers."

In the end, there are no conclusive answers until further studies say otherwise but for now, we need to take a more nuanced approach. We need to be more aware of where our fish is coming from, understand its connection to the sea, empower and build the capacity of fishers to ensure they release the mammal alive and overall reduce our pressure on the sea. That way at the very least, we can say with more clarity that these deaths are not caused by us.

For now, the water remains murky.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments