Muzharul Islam: An activist architect

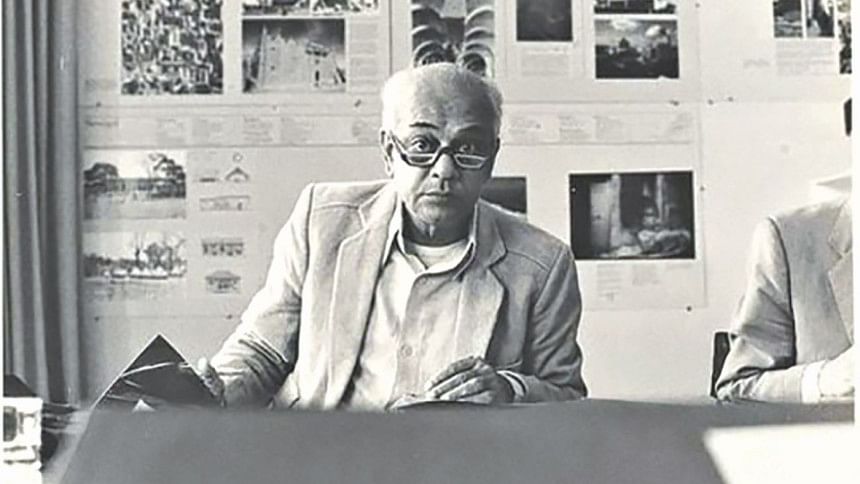

Today, December 25, is architect Muzharul Islam's (1923-2012) 94th birth anniversary. Not only was he Bangladesh's pioneering modernist architect, he was also an activist designer who viewed architecture as an effective medium for social transformation. His early work shows how architecture was deeply embedded in post-Partition politics.

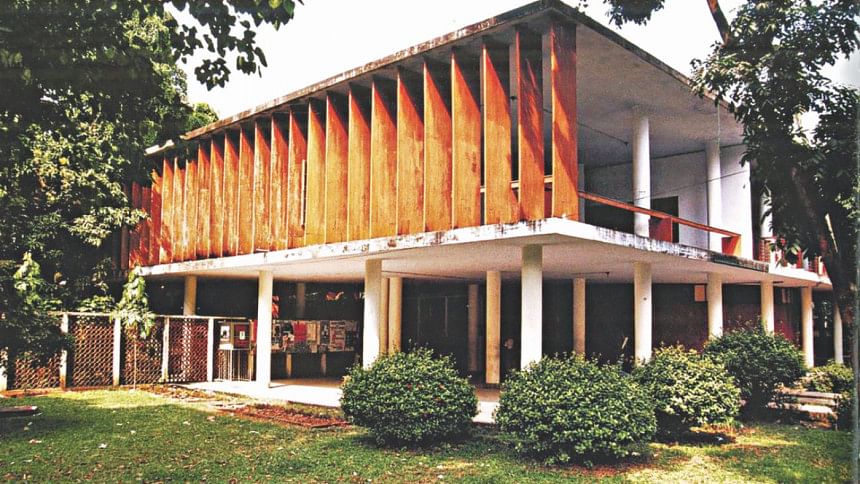

Consider his "master piece", the Faculty of Fine Arts (1953-56) at Shahbagh. At first encounter, the building presents the image of an international-style building, with a quiet and dignified attention to the architectural demands of tropical Bengal. Closer inspection, however, hinders the Eurocentric tendency to measure the building's "modernity" exclusively through a "Western" lens. A host of nuanced architectural modulations and environmental adaptations reveals how Muzharul Islam's work cross-pollinates a humanising, modernist architectural language with conscious considerations of climatic needs and local building materials.

The literature on South Asian modern architecture usually identifies the Faculty of Fine Arts as the harbinger of a Bengali modernism, synthesising a modern architectural vocabulary with climate-responsive and site-conscious design programmes. What has not been examined in this iconic building is how Islam's work also provides a window into the ways his architectural experiments with modernist aesthetics were part of his inquiries into the ongoing politics of Bengali nationalist activism.

After completing his Bachelor of Architecture degree at the University of Oregon, in June 1952, Muzharul Islam returned home to find a postcolonial Pakistan embroiled in acrimonious politics of national identity. The fragility of the pan-Islamic polity that sought to consolidate the impossible geography of Pakistan was evident. The religion-based, two-nation partition of the Indian Subcontinent into India and Pakistan was designed to create two separate domains for Hindus and Muslims respectively. Yet, Muslim Pakistan was already in trouble soon after the Partition of 1947. The newly minted country's two regions—East and West Pakistan, separated by 1,000 miles of Indian territory—clashed over their asymmetric power relationship, different languages, and, most of all, conflicted attitudes regarding how their divergent ethnicities and Islamic nationalism intersected.

The country's political power was centred on West Pakistan, while this lopsided power structure was further exacerbated by an ideological difference. The ruling elites of West Pakistan embraced a brand of political Islam that they believed would not only work as an ideological buffer against the perceived threat of Hindu-majority India, but also unify the different ethnic groups of Pakistan with an overarching Islamist spirit. Such a state policy alienated many secular-minded leaders, intellectuals, and professionals in East Pakistan, drawn more to a mediating relationship between humanist Bengali tradition and faith than to greater Pakistan's Islamic nationalism.

On February 21, 1952, less than a year before Muzharul Islam arrived home from the United States, the police opened fire on Bengali East Pakistanis protesting on the streets of Dhaka. The people of East Pakistan demanded the right to speak their language, Bangla, not Urdu—the language of the ruling elite in West Pakistan—which West Pakistanis had proposed as the national language of Pakistan. Some Bengalis, including students, killed during the political demonstration in Dhaka, were lionised as martyrs of the Language Movement in East Pakistan.

Muzharul Islam interpreted the prevailing political conditions in his homeland as a fateful conflict between the secular humanist ethos of Bengal and an alien Islamist identity imposed by the Urdu-speaking ruling class in West Pakistan. The turbulent politics in which he found himself influenced his worldview as well as his fledgling professional career. The young architect began his design career in a context of bitterly divided notions of national origin and destiny, and his architectural work would reflect this political debate. He felt the need to articulate his homeland's identity on ethno-cultural grounds, rather than on a supra-religious foundation, championed by West Pakistani power-wielders. Muzharul Islam's Faculty of Fine Arts embodied these beliefs.

With his iconoclastic building, Islam sought to achieve two distinctive goals. First, the building introduced the aesthetic tenets of modern architecture to East Pakistan. For many, its design signalled a radical break from the country's prevailing architectural language for civic buildings. These buildings were designed either in an architectural hybrid of Mughal and British colonial traditions, popularly known as Indo-Saracenic, or as utilitarian corridor-and-room building boxes, delivered by the provincial government's Department of Communications, Buildings, and Irrigation (CBI). The Faculty of Fine Arts was an unambiguous departure from the colonial-era Curzon Hall (1904–1908) at the Dhaka University, within walking distance of Islam's building, and the Holy Family Hospital (1953; now Holy Family Red Crescent Medical College Hospital).

Second, the Faculty of Fine Arts' modernist minimalism—rejecting all ornamental references to Mughal and Indo-Saracenic architecture—was a conscious critique of the politicised version of Islam that had become a state apparatus for fashioning a particular religion-based image of postcolonial Pakistan. By abstracting his design through a modernist visual expression, Muzharul Islam sought to purge architecture of what he viewed as the political associations of instrumental religion.

At Yale University in 1960, where he pursued a Master's degree in architecture, Islam met Stanley Tigerman, with whom he formed a design partnership to work in East Pakistan. Tigerman claimed that Islam's architecture was part of the same search for a Bengali identity that helped define the secular ideological foundation on which the new nation of Bangladesh was eventually built.

The Faculty's modernism hinges on Muzharul Islam's dual commitment to a secular Bengali character and universal humanity, a post-nationalist worldview rooted in the enlightenment ideals of Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), as well as his own education in both the East and West. A life-long student of Tagore, Islam refused to see any ideological conflict between Bengali mythos and modern notions of progress and rationality. What makes Muzharul Islam's work particularly important is that his architectural search was triggered by a peculiar political predicament resulting from the inversion of the very pan-Islamic argument that was used in the creation of Pakistan.

Today, the Faculty of Fine Arts has become an icon not only of art education in the country, but also of its modernist national aspiration. The much-celebrated cultural procession on April 14, the first day of the Bengali calendar, begins here. Art students create giant papier-mâché masks, birds, animals, and fish, which symbolise Bengal's agro-pastoral heritage. The building is part of the national narrative.

Happy birthday, maestro Muzharul Islam!

Adnan Morshed is an architect, architectural historian, and urbanist and currently serving as Chairperson of the Department of Architecture at BRAC University. He is the author of Impossible Heights: Skyscrapers, Flight, and the Master Builder (2015) and Oculus: A Decade of Insights in Bangladeshi Affairs (2012). This essay has been excerpted from his recently published article "Modernism as Postnationalist Politics: Muzharul Islam's Faculty of Fine Arts (1953-56)" in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. He can be reached at [email protected].

Comments