A G Stock's Memoirs of Dacca University

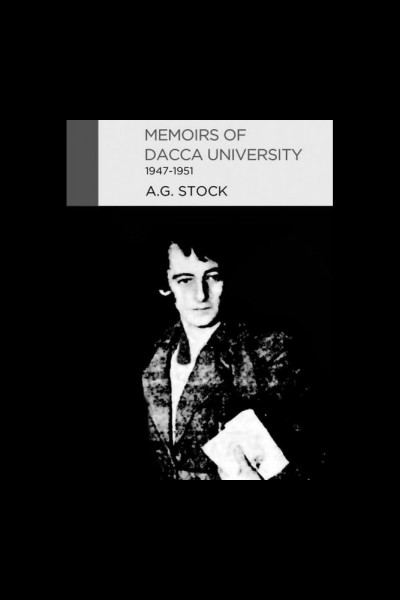

"The book is a memoir, not a history, and makes no claim to a historian's detachment or research." With this statement, A G Stock makes her point clear at the outset of her book, Memoirs of Dacca University 1947-1951, even though the memoir fervently records the tumultuous period in East Pakistan after the Partition and gives an insight into the causes leading to the Language Movement. First published in 1973 by Green Book House Limited, a new edition of the title went into print in 2017 by Bengal Lights Books with a forward by Kaiser Haq, and the current editor Khademul Islam's note, both stressing on the paramount significance of the book.

The memoir begins with Stock narrating the preface of her choosing a career in the East. After graduating from Oxford, she had happily settled into a life, wittily identified as a double life in London, teaching part time at a training college while also 'hard at work in colonial freedom movement,' an interest she developed during student time by collaborating with the anti-colonial student forum. It is this interest that finally led her to choose the job of a professor and Head of the English Department of The University of Dacca in 1947 where she stayed till 1951.

It was just an aftermath of the Partition. The new country Pakistan was yet to settle down as Stock correctly discerned "unlike India, which had been preparing for independence for years, Pakistan had only just begun to believe in its own existence." No doubt, both the country and the university were going through a rough patch. And in midst of this chaotic confusion, Stock landed, settled down and mingled with people from various walks of path with an easy grace and compassion.

A keen observer of people and places, Stock in her memoir launches into an evocative description of all the people she met and all the places she visited during her four years of stay in East Pakistan. She accurately describes her brief encounter with people on the SS Franconia like the young Pakistani army cadet who naively believed, "We simply can't visualize a country divided forever … we shall come back to a united India" (5), or the Bengali girl from Santiniketan who came up with this beautiful poetic line, "One should never hold on tightly to life." She portrays the activities of the small village boys who offered their services as porters: "A troop of brown boys in loincloths leapt from the bank and raced towards the steamer…. they went through the water like drapers' scissors through bales of cloth. (9)" As a literary scholar, Stock's narrative is often lyrical. The exotic natural landscape of Bengal that had immensely moved Stock were narrated in nothing short of a musical prose: "The Gangetic plain spreads out under blazing sunlight like a tapestry, endlessly monotonous, endlessly varied. (7)"

Stock's depiction of characters deserves special mention. The undersized twelve-year old boy, dressed in a shabby lungi carrying a small suitcase presented himself one day before Stock announces proudly, 'I businessman" (23). Then, there is Abdul, the superb cook reluctant to serve native guests; Kalipada, the English Department chaprassie who practically ran the department in the first month. He was theoretically illiterate but would look over Stock's shoulder and correct her spellings of names. Stock had the chance to meet and befriend some prominent personalities like Munier Choudhuri, Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta, Dr. Khan Sarwar Murshid and a few others. It was at this time when Mahatma Gandhi was shot dead, making Stock a witness of a memorable moment of history.

As mentioned earlier, the university itself was afflicted with numerous issues. It was also the primary centre of the revolution movements, full of marches, demonstrations and protests. Yet, it was no battle zone, and Stock and her students did engage into various literary and cultural activities. One such venture led her to translate some of the old Muslim poets of Bengal as well as modern Bengali poets like Kazi Nazrul Islam. Some of the translated versions were published in an English journal, New Values, a project of Stock's student Khan Morshid. She came across Jasimuddin, the poet who gave tremendous efforts and time to revive the Bengali folklore. Stock was instrumental in producing an abridged edition of The Vicar of Wakefield for use in the Intermediate course. Moreover, she delved deep into the issues of English teaching and the faulty examination system in the sub-continent. In some crucial ways, she was able to take more or less an objective view of the socio-political issues whether it was the Hindu-Muslim rifts, the communal riots, the language trouble or the student and chaprassi strikes. Throughout the memoir, she recorded the political ferment of that time, often raising important observations: "What's the use of an Islamic state if it doesn't translate the principles of Islam into a social order?" (84). With an insight so rare, she could predict: "I had an unacknowledged presentiment that the language question would issue in bloodshed" (204).

From the very beginning, Stock was aware of the tensed, troubled relationship between the East and West Pakistan. Though Pakistan was born as the homeland for Muslims of the subcontinent, there was nothing similar between the two regions except religion. The West Pakistan again and again launched assaults on the language and culture of the Bengalis leading to a series of fierce protests and strikes. Though Stock repeatedly claimed herself "as an onlooker, not an actor," her sympathies were all for her students who lightened the tough days and the colleagues whom she deemed a privilege to know. Her tone is marked by empathy for "the impracticable Bengalis" (112) and their causes throughout the memoir. It is this compassion for her pupil and colleagues that made her visit them in jail or stand as a guard in the women's hostel during communal riots. After a brief holiday in New Zealand, when she returned to East Pakistan, she claimed it was "like an odd homecoming perhaps, but it felt like dropping back into a life where I belonged" (162). Her close association with the students and colleagues eventually caused indirect friction with the Pakistani authorities. She was under surveillance to the extent of her private correspondences being traced by intelligence agencies. It was at this time, she decided to leave East Pakistan. But her profound feelings for Bengal and the Bengalis did not lessen by any means which perhaps compelled her to make a comeback after twenty years in 1972 to a newly liberated country, Bangladesh.

Finally, it cannot be denied that memoirs often tend to be monotonous and could be taken as a dull, rambling work that readers read with feigned interest. But Stock's memoir is an exception not only for its palatable prose spiked by utter lucidity but also because of its vast range. It's a fine blend of historically significant events or merely a topical event, meeting with some very well-known or perhaps totally unknown characters, a trip to the village or abroad, the description of the beauty of Bengal or simply some facet of nature and her acute observation of various socio-political issues. Some may find it to be more than a memoir with its wide canvas, giving the readers a slice of the sub-continent. Be it philosophy, history, rhetoric, or any other focused discipline that one finds interesting, he or she can always read Stock's Memoir in order to conduct both a factual and a narrative investigation regarding the post-partition, pre/post Liberation War times in Bangladesh.

Marzia Rahman is a translator and short story writer from Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments