Talks history offers food for thoughts

The ruling Awami League will begin talks with opposition political alliance Jatiya Oikyafront tomorrow with a backdrop of an eventful saga of success and failure in the history of dialogue in Bangladesh politics.

A day after tomorrow the AL will hold a dialogue with Bikalpadhara Bangladesh.

In the following we have reproduced the article, by Shakhawat Liton published in 2016, analysing the history of political dialogues in the country.

The history of dialogue in Bangladesh politics in the last 25 years is an eventful saga of success and failure.

One may draw inspiration from successes to resolve a political dispute. Others may follow ways how to deepen a crisis, let alone work towards its resolution.

Take some shinning and gloomy examples of dialogues as President Abdul Hamid opened talks yesterday with political parties seeking their opinions to form an acceptable Election Commission.

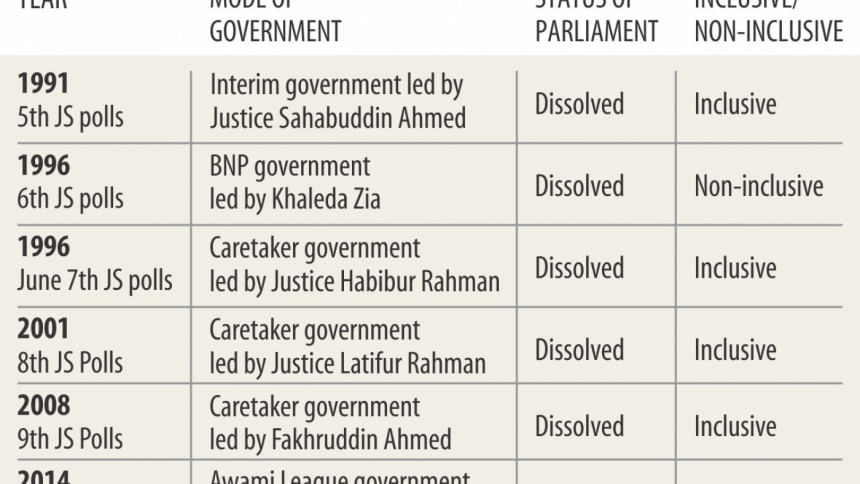

After the fall of autocratic ruler Gen Ershad, the first instance of successful talks among political parties paved the way for smooth transition to democracy in 1991.

They reached an agreement through talks and requested then chief justice Shahabuddin Ahmed to lead the interim government after Ershad resigned as the president.

The Shahabuddin government was successful in leading peaceful transition to democracy through holding a free and fair election in February 1991.

Again, parliamentary democracy was brought back through peaceful means following a consensus between all political parties.

In the run up to the 1991 elections, the then EC, led by Justice Abdur Rouf, held a successful dialogue with 67 political parties resulting in unanimous formulation of an electoral code of conduct. In the talks, all the political parties agreed to abide by the agreed code in electioneering.

The CHT Peace Accord was another significant outcome of successful talks between the government and the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Samhati Samiti in 1997. This brought an end to decades-long insurgency in the three hill districts.

During the Fakhruddin Ahmed-led caretaker government, the Election Commission, led by ATM Shamsul Huda, had held several rounds of talks with political parties and was successful in bringing sweeping electoral reforms, including mandatory registration of the political parties with the EC.

Take two more instances of holding of successful talks between the AL and the BNP.

Under the mediation of the then Speaker, leaders of the then ruling AL and the BNP agreed on January 14, 1997 to resolve a crisis in parliament.

Leaders of the AL and the BNP sat for talks again on February 2, 1998, to resolve the stand-off in parliament. They reached an understanding and the BNP returned to the House ending a boycott.

GLOOMY CHAPTER

The other side of the dialogue story is a sad one indeed. Whenever talks collapsed, it brought disastrous consequences. On every occasion, the country's people, economy and democracy restored in 1991 had to pay dearly.

Failure of negotiations between the AL and the BNP mediated by some eminent persons in October 1995 to resolve the political crisis resulted in massive street violence and eventually a one-sided parliamentary election in February 1996.

The then BNP-led government formed through the election was forced to introduce a non-partisan election-time government system in weeks. It was also forced to step down at the end of March 1996, paving the way for fresh parliamentary election in June 1996.

It was again the BNP-led government that created a political crisis by increasing the retirement age of the Supreme Court judges through a constitutional amendment in 2004.

The amendment paved the ways for chief justice KM Hasan to become the chief adviser of the election-time caretaker government.

The AL-led opposition vehemently rejected the constitutional amendment, saying they would not accept Justice Hasan as the chief adviser. It came up with a set of electoral reform proposals including the one for the formation of the EC on the basis of consensus among the political parties.

The BNP-led government did not pay heed to the AL proposals. It appointed a Supreme Court judge, MA Aziz, as the chief election commissioner and other election commissioners. This worsened the political situation.

The Aziz-led EC was itself in disagreement over the preparation of a fresh voter list. To resolve the problem, it decided to hold talks with political parties seeking their opinion on it. It invited more than 100 political parties. The AL-led opposition alliance boycotted the talks which turned into a farce, drawing the EC into controversy.

Towards the fag end of its tenure, the BNP-led government agreed to sit for talks with the AL to break the political deadlock. Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan and Abdul Jalil -- deputies of their parties -- held several rounds of talks in Jatiya Sangsad Bhaban.

Emerging from talks, Bhuiyan and Jalil kept assuring the worried nation that they were making progress. But it was a bluff. The talks yielded no positive results, as both the parties stuck to their guns.

The tenure of the BNP government came to an end with the crisis remaining unresolved. Street violence flared up. Then president Iajuddin Ahmed opened talks with the political parties to break the impasse.

The BNP rejected the AL's proposal for an alternative to Justice Hasan.

All of a sudden, Iajuddin, on the BNP's advice, assumed the office of the chief adviser, ignoring the constitutional provision. The crisis worsened further.

Some of his advisers, however, moved to break the political deadlock by holding talks with political parties. They prepared a package of proposals in this regard.

But Iajuddin, allegedly on the BNP leaders' advice, stopped the advisers' initiatives. He even appointed two more election commissioners.

At one stage, the AL-led alliance pulled out of the election scheduled for January 22, 2007.

Yet, the Iajuddin-led government was determined to hold the one-sided election. The AL-led alliance intensified street agitation and announced that they would resist the polls. The country was plunged into a complete political chaos. In such a situation, the armed forces intervened. A state of emergency was declared on January 11.

The crisis centring the election-time government prevailed again in 2011 when the AL-led government abolished the caretaker government system by amending the constitution.

The constitutional amendments not only allowed the AL to stay in power during the election, but also allowed all MPs seeking re-election to stay in office.

This time, the BNP-led alliance took to the streets for bringing back of the non-partisan election-time government. The AL rejected the demand. A political deadlock prevailed ahead of the 2014 election with escalation of violence.

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina then offered to form an all-party election-time government and invited the BNP to join. But Khaleda Zia rejected the offer and kept demanding a reintroduction of the caretaker government.

Hasina even made a phone call to Khaleda inviting her to sit for talks, but she refused.

The United Nations sent its key official Oscar Fernández-Taranco in early December of 2013 to Dhaka for a four-day whirlwind visit to discuss with political leaders a mutually acceptable formula to hold “inclusive, non-violent and credible” election.

He held several rounds of talks with AL and BNP leaders. But the talks failed to break the deadlock, resulting in a one-sided parliamentary election on January 5, 2014, and 153 MPs elected uncontested.

HOPE AGAINST HOPE?

The above examples of success and failure offer food for thought for top politicians who are meeting the president.

During the talks, the political parties are supposed to give their opinion on the formation of the new EC in February, which will conduct the next parliamentary election after two years.

The president's initiative generated hope for the formation of an acceptable EC though the record is not much inspiring. In 2012, the then president Zillur Rahman formed the present EC, led by Kazi Rakibuddin Ahmed, through a search committee following talks with political parties.

But the current EC is apparently one of the weakest and controversial ECs. It conducted the January 5 one-sided parliamentary election. Almost all the local government elections held since 2014 were mired in controversies.

A strong EC now matters more than ever due to the absence of an election-time non-partisan administration. In such a situation, the role of the EC would be significant in conducting the next parliamentary election.

The president's move came hot on the heels of BNP chief Khaleda Zia's proposal for formation of the EC on the basis of consensus among the political parties.

The party might urge the president to take steps for forming an all party election-time government during the next general election.

Success of the president's move, however, depends on the political will of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina who is chief of the ruling AL. Because, the president has no power to do anything on his own without the advice of the prime minister in this regard.

The talks might not yield positive outcomes if the current trend of distrust remains among politicians. If political parties draw inspiration from their previous successes in resolving disputes, they might be able to move away from the confrontational political culture and begin a fresh chapter of cooperation, which would contribute to making the next parliamentary election participatory.

So, success of the talks between the president and political parties is immensely important.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments