A reminder of the nearly unwinnable hand Yunus was dealt

History shows that the aftermath of popular revolts—particularly those that overthrow authoritarian regimes—is marked by chaos and uncertainty. What Bangladesh is currently facing—economic instability on pocketbook issues, such as exorbitant prices of essentials, a feeble investment climate, and a war of words among political stakeholders with competing vested interests—is a predictable symptom of a messy but necessary political transition.

In reality, that transition is underway—not through an overhaul of how politics functions in Bangladesh but within the pre-existing paradigm of a flawed system, through gradual, incremental steps towards democracy. Finding the sweet spot that constitutes a liberal, multi-party ecosystem will take decades, not months. It depends on both a good-faith commitment and the implementation of that commitment by political actors through self-reflection, public policies, and rhetoric that differ extensively from what Bangladesh has experienced in the past.

Yunus leads a team that, for all its flaws, has shown a willingness to listen to criticism rather than suppress dissent. However, testing the public's patience is the government's failure to adequately respond to those criticisms by matching words with actions. The public's patience is considerable, but it is not infinite and will inevitably reach its limits. Yunus' announcement that elections will take place sometime between the end of 2025 and mid-2026 has helped calm nerves slightly, offering a skeletal electoral roadmap.

Many segments of society, silenced for 15 years, are voicing their frustrations on a range of issues without the fear of reprisal. This sudden release of anger, while cathartic for some, has added to the government's woes. A vested quarter, still convinced that Hasina's political chapter is far from over, are intent on breeding chaos and disrupting the brittle equilibrium defining the social contract between an anxious population and an inexperienced government.

A government, neither elected nor politically sharp yet burdened with the task of navigating a minefield of expectations, frustrations, and entrenched divisions, is far from ideal. However, the current situation simply reflects the raw, anarchic truth of a nation still trying to figure out its next steps.

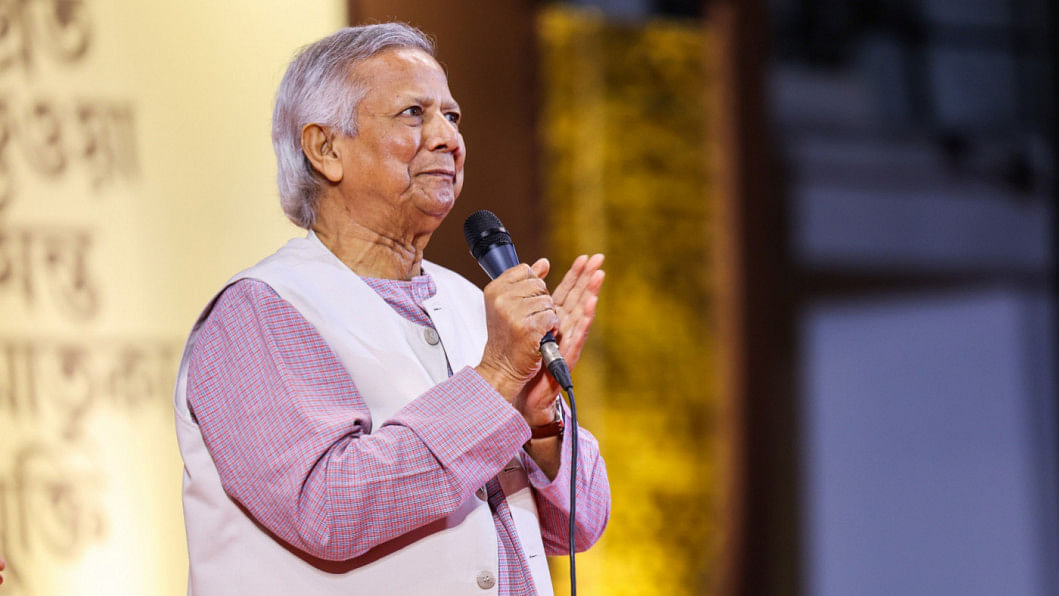

A sentiment has taken root in Bangladesh: Yunus is an honest man with good intentions, a philosopher who has wooed international leaders every time he has travelled abroad since taking the reins of government. At the recent World Economic Forum conference, he was in fine form. In Bangladesh, though, he seems out of his comfort zone, struggling to steer the ship of state—a ship he did not want to captain.

There are many steps that, as chief adviser, Yunus could and should have taken but has not. Critics have examined these shortcomings in depth. But it is the nation's duty to continuously remind itself of the context in which Yunus finds himself in the position he occupies today and why he deserves a fairer assessment.

To begin with, consider how Yunus assumed office. He was preparing either to remain abroad or return to Bangladesh to face imprisonment under a regime that sought retribution. That regime, led by a prime minister with a personal vendetta against Yunus, resented the universal respect he commanded. His stature was an insult to the fragile ego of an autocrat.

In the aftermath of August 5, a group of young student conveners, most in their 20s, approached Yunus with an emotional appeal. They summoned him back to Dhaka from Paris, delivering an unambiguous message: you have to return to take the role of head of government in Bangladesh. And they were right.

Frankly, there was no other option than Yunus. At that moment, and even today, no one else other than him had—or has—the moral legitimacy to unify a fractured Bangladesh. Yunus brought an aura of hope, a balm for a country reeling from weeks of state-sponsored carnage. Mob violence still occurred, but viewed contextually, things could have been much worse. Nonetheless, being a symbol of national unity is one thing. Governing is another matter entirely.

His advisory council has attracted valid criticism due to the underperformance of certain individuals. According to Yunus's own admissions in a candid conversation with New Age editor Nurul Kabir, he was presented with a shortlist of names—likely suggested by the student conveners—and chose individuals he knew personally. Unlike previous chief advisers of caretaker governments, who had the luxury of time to prepare and the clarity of purpose, Yunus inherited a state apparatus with neither.

The caretaker governments of 1991, 1996, and 2001 operated under three-month mandates to organise elections. They benefitted from defined goals, established timelines, and institutional preparation. In contrast, Yunus was tasked with a much broader and less defined mission: to reform a system riddled with corruption, dismantle entrenched authoritarian structures, unite political parties, hold elections, and manage the day-to-day affairs of the state. There was no roadmap, no consensus on priorities, and no clarity on the duration of his administration.

Most members of his advisory council have no experience in government, including Yunus himself, as he often reminds the public. He could not appoint figures closely tied to the Awami League or BNP, nor could he include anyone seen as ideologically extreme to the left or the right. This resulted in a team that lacks administrative skills and ideological cohesion. While these shortcomings are real, they reflect the impossible deck of cards Yunus was dealt.

The politics Yunus must navigate are no less fraught. The BNP demands elections as soon as possible with minimal reforms, pushing the idea that an elected government is urgently needed. Meanwhile, frontline student leaders have begun to display signs of inexperience, veering into unnecessary ideological debates, such as calls to amend Bangladesh's state ideology, rather than focusing on designing a coherent policy vision for the future. Activism, for all its courage and energy, has not translated into the kind of maturity needed post the uprising.

Then there are the religion-based factions, including Jamaat-e-Islami, which seek to steer Bangladesh in a direction likely at odds with a sizeable segment of the country. Considering all this and more, Yunus has become an umbrella shielding a nation from local and international conspiracies, striving to cocoon citizens from conflict with one another to the best of his ability, battered by competing political, ideological, and generational storms.

Compounding these challenges is the bureaucracy. The civil service, entrenched in inefficiency and outdated practices, has become a barrier to both reform and daily administration. Yunus has faced a public service designed to resist change, still bearing the influence of the previous regime. From law enforcement's failure to carry out its responsibilities to the continued dominance of syndicates, the bureaucracy has proven to be an almost insurmountable obstacle.

The greatest challenge lies ahead. The recommendations from various reform commissions must now be either agreed upon, ditched, or left for the elected government to pursue, requiring negotiation among political stakeholders. Yunus has taken on the responsibility of building consensus—an extremely difficult task. He has positioned his government as a facilitator without its own agenda, suggesting that those expected to lead Bangladesh after the elections should take the wheel in determining what is best for the country.

On paper, this approach seems inclusive—some might even call it democratic. The real question, however, is whether an 84-year-old man, who has lived a remarkable life, achieved nearly everything one can aspire to, and brought international recognition to Bangladesh, can rise to meet the moment and what is arguably the biggest test of his life. The people of Bangladesh have little choice but to place their faith in a man who, throughout his storied career, has rarely disappointed his nation. Criticise his government we will, but place our trust in him we must. Good luck, Dr Muhammad Yunus.

Mir Aftabuddin Ahmed is a public policy columnist. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments