Watch watching

Since long I have been intrigued by Desmond Morris's Manwatching (1977), admittedly one of the few books that I have gone through, not as much for its brazen content as for the very fact that the writer could think of a topic as absorbing as watching human beings. We all more or less do that, i.e. watch others around us (artfully or unashamedly), but Desmond (no, I do not know him on a one-to-one basis) transformed his zoology studies into a hobby; or, was it the other way around? No wonder then that a favourite quote of the ethologist, surrealist painter and popular author is 'I viewed my fellow man not as a fallen angel, but as a risen ape'. That really does bring out the monkey in the Englishman.

It is now clear that BCS examiners have been watching their examinees for a long time too. Based on what they have observed, this year over two lakh government service hopefuls have been barred from carrying a watch (wrist, pocket or electronic) to the 162 examination centres during the preliminary test. The irony is many among those who took that momentous decision did wear a watch or carry one when they appeared in this life-changing exam.

The test-takers are increasingly feeling unprotected after the previous ban on calculators, mobile phones and electronic devices. One wonders what will happen if further observation uncovers another common means of cheating – making notes on the underside of one's non-writing arm. How do I know that? Well, more on that some other day. What if an examinee arrives with a designer dupatta or an uttorio made of all the answers to the probable (leaked or otherwise) questions? This divesting of one's personal belongings has to be stopped at some point if only to avoid pain (disarming) and embarrassment (disrobing).

Some watches are just that, they tell the time if they are working. They should be of no use to any cheat anywhere, unless its brand is Psyche and the expected question is: What is another word for 'soul' that begins with a P?

There are other useless watches, such as the ones that stop working during exams, occasionally to the peril of the wearer. When asked, not all invigilators are in a mood to tell a helpless examinee the time, simply because the invigilator already has a job. Mui ki honu re?

Some watches are many times more expensive than the starting salary of a government employee. I am not referring to the Phoenix-shaped Cartier that is priced at $2.755 million, or to the Tourbillion Diamants Blancpain having a price tag of $1.812 million. You read those numbers right. I am assuming (and logically so) that of the more than 30 million watches with a price higher than $1,000 that are sold each year, a few find their way into our examination halls. We are indeed gratified that persons of such noble backgrounds are opting to serve the people. I believe some invigilators would tell them the time. Psst! What do these ultra-costly watches do besides telling the time? You guessed right, I do not wear a wristwatch.

The point is why ban watches (and what more articles will you bar?) when the solution lies in the question-setter gaining more knowledge than the wristwatch, rising above the calculator, and giving more time in setting intelligent and perceptive questions that transforms even an eight-digit calculating time-telling digital gadget into a vegetable. Please don't ban bananas; they are the lifeline of many students and scholars.

For instance, if a question seeks to know how many hands a wristwatch has, it is a not a legitimate question these days because with the options available some watches have more than two. Besides making the one possessing a no-hands digital clock go berserk, it will compel the examinee to take a look at his/her watch, which will tantamount to copying. Got you! You can imagine the TV scroll: Thousands expelled for watching their watch by examiners who were watching.

A better approach could be to ask about the greatest benefit of, say, a pucca road instead of making them watch the watch by asking the road length that had to be built if 33 percent of a 100km stretch was to be made pucca.

Why not set a question asking which country (among the options given) does not manufacture watches instead of which does, and why? Poke their intelligence instead of prodding their calculating skills. Let us be inspired by the method of 'open book' exams.

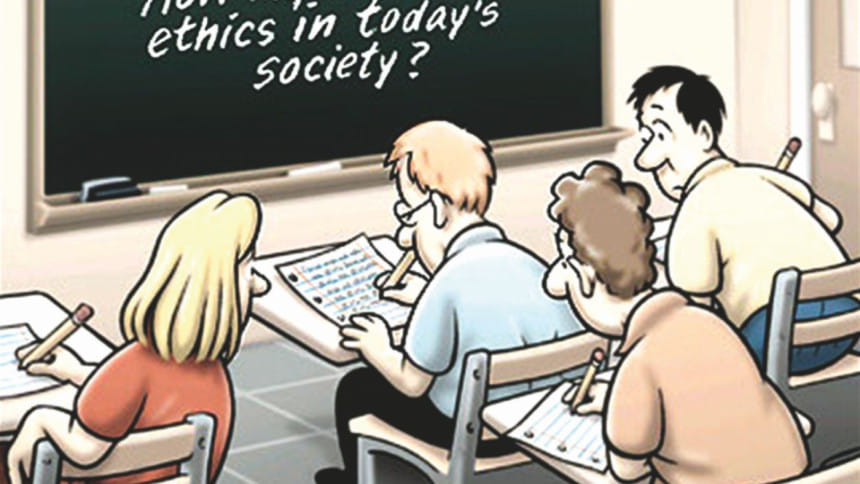

But, what if a receiver of text messages is disguised as a wristwatch? Aha! To begin with, we could teach our children from as early as primary school level that cheating is a sin. We could transform our societies to condemn cheats and penalise them in all sorts of ways. But, we do not.

Sadly though, there are cheats at the highest institutions in our country, our universities, where teachers have cheated in their professorial applications, and held on to their jobs, with the help of conniving vice chancellors; the reason being poor schooling and dubious social upbringing, and a society debased enough to accepting the wrongdoers.

It is thus an almost impossible task to catch them at BCS level, if we have not taught them at primary. Cheating has become the norm, honesty an exception. Instead of awarding the honest, which we sometimes do most ceremoniously, we should deal exemplary punishment to the cheats.

The writer is a practising Architect at BashaBari Ltd., a Commonwealth Scholar and a Fellow in the UK, a Baden-Powell Fellow Scout leader and a Major Donor Rotarian.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments