The Covid-induced stress factors impacting our students

There have been changes in the way we live and the way we die. We have learned to live carefully during this time of the pandemic, yet we have been dying carelessly. We have learned to live in isolation, yet death seems to be in no mood to spare us alone. News of death reaches us through social media. Facebook newsfeeds now run like a bottomless obituary page of a regular newspaper; you get tired of writing condolence messages or posting RIP or sad emoticons. You keep on sharing sympathies only to realise that the negativity has sucked the emotion out of you, and in the digital space, you are simply writing codes that lack human empathy.

As an educator, who has been teaching at the university level for the last 27 years, I had to jump through hoops to move from physical to digital classrooms due to this pandemic. The new tricks for old bones have been overwhelming for many senior faculty members. The transition has made me realise how the last 13 months have turned me into an automaton. Teachers are performers who get their performative energy from their classrooms by interacting with their students. The interaction in a virtual classroom is not the same as in a physical classroom. Most of our students do not turn on their videos during our Meet or Zoom sessions due to privacy or bandwidth reasons. The techniques that you learn from the internet or pedagogical experts for breakout interactive sessions often do not apply in our circumstance because of the lack of digital resources. For instance, many students may not have the data to watch a video that you want them to watch, or they may not have the apps and features on their devices to take full advantage of the e-classes. I know of a student who had to type three 2000-word assignments for his mid-term on his phone as he did not have a laptop.

Although the classroom screen is equally apportioned, each participating member has a unique tale to tell. The semblance of equity that you see on your screen belies the inequity that exists on the other side of the black mirror of our computers or phones. We do not know how many people are crammed in a small room from where the student is attending the class; by the same token, a teacher does not know that his lecture is being heard by many unintended listeners. A classroom is no longer a protected space to liberate your minds, it is in the world wide web, where a teacher does not have any control over the contents being shared. As a teacher, I must be extra careful about what I am saying or not saying in a classroom.

I was attending an e-summit recently where one history professor in the US was saying how these online classes have brought her academically closer to her husband, who is an anatomy professor. The couple have never seen each other in their classroom settings as they belong to two different disciplines. While the wife was lecturing on the Middle Age response to plague, the husband listened. And when the husband was lecturing on what disease can do to the body, the wife listened. They realised how literature and historical narratives aptly captured the effect of the disease in images or artefacts. This is a serendipity for the couple who found new ways of collaborating in research, bridging medical science and humanities. The accidental participation in each other's classes created a new familial bond.

On the other side of the spectrum, we come across many stories that underline the lack of family bonding in coping with mental health disorders. We have heard about the increased number of cases of anxiety, depression, insomnia and suicidal thoughts that grew out of the lack of family support. Covid-impacted low-income, poverty or joblessness has created unprecedented frustration. Many university students feel helpless as they see their parents going through lifestyle compromises or adjustments due to this disease. They are in a stage of life where they have the desire to help their parents during this time of need, yet they are not fully ready for the workforce. A study on the mental health of students during Covid-19 in Bangladesh found an association of depression-anxiety-stress (DAS) with older (25–29 years) rather than younger (18–24 years) students. This is not hard to discern as the disease has evidently delayed or stalled the academic life of many.

As a nation, we were all set to leverage demographic dividends, taking full advantage of the high number of the population in their prime age to contribute to society. The pandemic has suddenly brought the same age group under extreme duress. Their hopelessness and frustrations can have a long-term effect on our social fabric. I do not think we are addressing the issue enough in our Covid-19 responses.

At my university, ULAB, we are working with two professional bodies—Maya and Moner Bandhu—to give round the clock counselling services to our students. In addition, we have included mental health as essential skills in our curricula. We also have a unique partnership with an international leadership programme with a project called "My sister's keepers", where female students form a self-support group. The more we invest in the psychosocial wellbeing of our students, the more we learn how little we are doing to take care of the mental health of our young generations.

A pre-pandemic study showed that 16.18 percent of people in Bangladesh suffer from mental disorder. This was in 2019. We do not know how the number has changed in the last two years, but we do know that 94 percent of them do not get support from psychiatrists. There is still stigma attached with going to a "shrink". But when you hear that in a country of 16 crore you have a little over 200 trained mental health doctors—there are reasons to be worried.

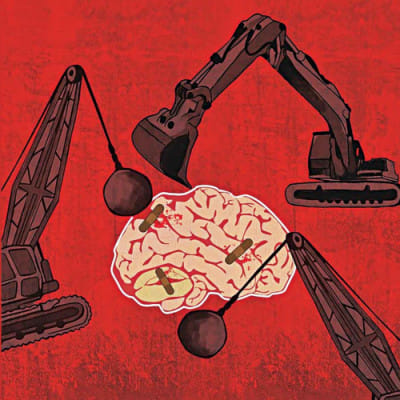

Once we see the full picture of the havoc wrought by the coronavirus, we will realise the need for a multi-sectoral response. Supplying oxygen and ventilators or handing out Eid relief can only scratch the surface of the problem. What lies beneath is a bigger problem that will require a humane solution. The pandemic has made us turn to machines. But if we do not want to turn into machines, we better start searching for ways to deal with the stress factors.

Shamsad Mortuza is Pro-Vice-Chancellor of the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB), and a professor of English at Dhaka University (on leave).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments