Development prerogatives for South Asia’s economic progress

In 1960, China's GDP per capita was USD 89.52. Until about the mid-1990s, China was a low-income country, with a per capita income of USD 317 in 1990. Throughout these three decades, China's per capita income was not much different from the three major South Asian countries—Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. China's growth trajectory broke away from the rest since 1995. Its per capita income in 2020 was around USD 10,500, compared to that of Bangladesh (USD 1,968), India (USD 1,900) and Pakistan (USD 1,193).

During this period of rapid growth, China lifted millions of people out of poverty. In 1990, there were more than 750 million people—about two-thirds of the population—living below the international poverty line (USD 1.90 a day) in China. By 2012, that number had fallen to fewer than 90 million, and by 2016 it had fallen to 7.2 million people (0.5 percent of the population), suggesting that roughly 745 million fewer people were living in extreme poverty in China compared to 30 years ago.

China has formally overtaken Japan in 2010 as the world's second largest economy, accounting for about 25 percent of global GDP or output. In 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), it accounted for 4 percent of the world's exports, and by 2017, that had risen to 13 percent. China's foreign exchange reserves, the largest in the world, rose to USD 3.22 trillion in May 2021.

Having grown in such a staggering fashion, unprecedented in recent history of the world, China's economy is facing structural headwinds given adverse demographics, tepid productivity growth, and the legacies of excessive borrowing and environmental pollution. These challenges require attention, with short-term macroeconomic policies and structural reforms aimed at reinvigorating the shift to more balanced high-quality growth.

The government recently highlighted achieving common prosperity as a key economic objective, reinforcing signals of a possible shift in policy priorities towards tackling income inequality. The Chinese government has made innovation a top priority in its economic planning through a number of high-profile initiatives, such as "Made in China 2025," a plan announced in 2015 to upgrade and modernise China's manufacturing in 10 key sectors in order to make China a major global player in these sectors.

Salient features of China's role

Since as early as 1950, China has been leveraging its strong history of domestic achievements in development to support other "developing" countries through its South-South cooperation and in the 70 years since, has grown into a preeminent provider of financing for global development. According to the Chinese government's 2021 White Paper, "China's International Development Cooperation in the New Era", China spent RMB 270.2 billion (USD 42.0 billion) on its international cooperation efforts in total between 2013 and 2018 (approximately RMB 45 billion or USD 7.0 billion annually); however, this represents only a fraction of China's overall engagement in low- and middle-income countries and does not account for its significant non-financial contributions to development.

Despite its increasingly important role in financing global development, the Chinese government has made it clear that its development cooperation is categorically different than that of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) donors. The government considers China to be "the largest developing country in the world" and, as such, views its development cooperation efforts as "a form of mutual assistance between developing countries". China considers its "South-South cooperation" to be "essentially different from North-South cooperation".

According to the 2021 White Paper, between 2013 and 2018 China allocated RMB 270.2 billion (USD 42 billion) to foreign assistance. The White Paper only provides an aggregate figure for these six years, but if divided equally, this amounts to an average of RMB 45.0 billion (USD 7.0 billion) annually. Just over half of these funds took the form of interest-free loans and grants, while 49 percent were concessional loans, meaning loans subsidised by the Chinese government with a preferential interest rate of 2-3 percent with 15-20 years maturity and a grace period of five years. Also, 4 percent of loans was interest-free loans, usually, with a 0 percent interest rate, 20 years maturity, and 10 years grace period. The other 47 percent of China's foreign assistance during this period was given as grants.

A comparison of the 2014 and 2021 White Papers also reveals a shift in the concessionality of China's foreign assistance. In relative terms, China has increased its use of grants from 36 percent of foreign assistance in 2010-2012, to 47 percent in 2013-2018.

China's BRI has two main components and five pillars. The components are an overland Silk Road and Economic Belt connecting China with Europe, the Middle East, and Central and Southeast Asia and a Maritime Silk Road including the construction or improvement of ports along the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, and South Pacific. The pillars include infrastructure, trade, financial connectivity, policy, and people-to-people exchanges. The BRI spans 65 countries that, according to a 2018 analysis by Morgan Stanley, accounted for 30 percent of global nominal GDP, 40 percent of global GDP growth, and 44 percent of

the world's population. This analysis also suggests that China's overall spending on the BRI could reach USD 1.2 to USD 1.3 trillion by 2027. The total announced investment is as high as USD 8 trillion.

Climate change response is mentioned throughout the White Paper including a section on environmental protection; however, there is no reference to the Paris Agreement or indications that China plans to mainstream climate objectives within its development programming. Rather, it mentions the BRI South-South Cooperation Initiative on Climate Change, its support for low-income countries trying to mitigate the effects of climate change, the establishment of a South-South Climate Cooperation Fund (SSCCF), initiatives to support low-and middle-income countries making the transition toward renewable energy, and environmental management and sustainable development training programmes.

China has emphasised health in its development programme for decades and has grown into a major player in this sector. Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, in particular, China has been promoting the health aspect of its BRI, what has been called the "Health Silk Road" or China's efforts to build a "community of common health for mankind". The 2021 White Paper outlines China's commitment to making Covid-19 vaccines "available as a global public good once they have been developed and applied in China".

Recent role in South Asia

China has embarked on a grand journey West. Officials in Beijing are driven by aspirations of leadership across their home continent of Asia, feelings of being hemmed in on their Eastern flank by US alliances, and their perception that opportunities await across Eurasia and the Indian Ocean. Along the way, their first stop is South Asia, comprising eight countries—Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka—along with the Indian Ocean (particularly the eastern portions but with implications for its entirety). China's ties to the region are long-standing and date back well before the founding of the People's Republic in 1949.

China's main asset is its economic levers of influence, and Chinese actors are proactive in wielding these. China is helping to construct mega infrastructure projects in almost every country in South Asia; in most cases with money that it has lent them. Its loans to Sri Lanka were at USD 4.6 billion in 2020, and the overall figure for Maldives is believed to be between USD 1.1 billion and USD 1.4 billion. According to the IMF, Chinese loans to Pakistan stood at USD 24.7 billion by April 2021. Figures from the Ministry of Finance show that the total outstanding Chinese loan to Bangladesh was around USD 2.6 billion in fiscal year 2019-2020.

"Debt-Trap Diplomacy", is a widely used narrative against China, by the Western and Indian media, suggesting that China really has a "Machiavellian strategy". However, in-depth independent studies found no "debt trap" in the four countries namely Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka, most often cited as an example of debt-trap diplomacy, has an overall debt management problem. Studies in 2020 put Sri Lanka's external debt to China at about 6 percent of its GDP. Other countries like Nepal and Bangladesh have been prudent in choosing their funders and methods of financing, often choosing traditional multilateral institutions or other bilateral lenders as partners.

In recent years, the most powerful sources of Chinese influence in the four South Asian countries—Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka—have been commercial and financial. This is reflected in high-value project finance and operations partnerships, not least for the Hambantota and Colombo port projects in Sri Lanka and the Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project in Bangladesh. Without exception, the governments of the four countries have described China as a crucial development partner, either as a funder or in providing technological and logistical support. Additionally, it is the biggest trading partner of goods for Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and the second-largest for Nepal and Maldives. Chinese investors have been the largest source of FDI pledges to Nepal for six consecutive years till 2020-2021, with more than half of the country's total FDI in the 2018-2019 fiscal year. However, the economic element is increasingly intertwined with political, government, and people-to-people aspects of these relationships.

Several Confucius Institutes have opened in Bangladesh in quick succession. In Nepal, multiple schools have made Chinese-language courses compulsory after the Chinese government offered to cover the salaries of the teachers involved. In Bangladesh, journalists have been awarded one-year, all-expenses-paid fellowships to Chinese institutions, and multiple newspapers have worked with the Chinese embassy to coordinate roundtables on the benefits of the BRI for the country.

The pandemic has created opportunities for China to work directly with the four countries in new ways—on the provision of medical equipment, biomedical expertise, and capital for coronavirus-related needs. In April 2021,

Foreign Ministers of China, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh agreed to deepen cooperation as South Asian countries are facing a new wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Changing geo-politics and Bangladesh

Chinese President Xi Jinping's visit to Bangladesh in October 2016 was a landmark one owing to a number of factors. After three decades, a Chinese President visited Bangladesh, signifying growing importance of the country in South Asia's economics and geo-politics. A number of high-profile investments and other business deals worth billions were agreed during President Xi's trip. The mega projects under implementation are examples of cooperation.

There is no denying that the United States remains the top global power. However, the nation is in a relative decline. This is largely due to the rise of China and a number of other emerging economies including India. The global economy's shifting centre of economic gravity towards Asia is making China and India two powerful economic engines as well as geo-political rivals.

Geo-political rivalry between the two Asian giants means smaller South Asian countries, including Bangladesh, could face mounting challenges in managing a balanced relation with them in the years ahead. Nevertheless, it is critical for these countries to maintain balanced ties with India and China, preserving their national interests. Too much alignment with a single power risks the country becoming a vassal state.

For centuries, China had been well-connected with its immediate neighbours as well as Europe, Middle East and Africa through the Silk Road. Beijing intends to re-establish this historical connection, creating a vast network of railway, energy pipelines, highways and modernising border points.

Beijing is also developing new institutions and channelling funds, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Silk Road Fund, to support the largest undertaking since America's Marshall Plan, implemented after World War II.

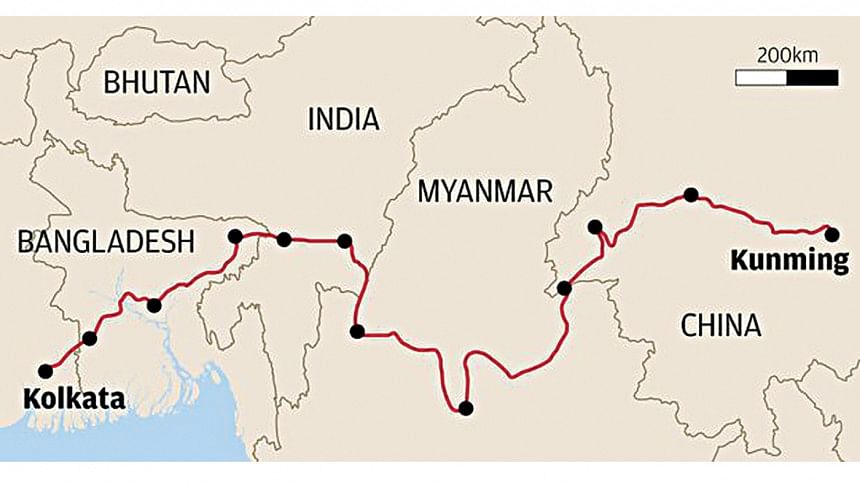

The BCIM Economic Corridor, involving Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar, is also a part of OBOR. However, the progress of BCIM has been less than satisfactory, although its origin dates back to the 1990s, as China and India's strategic rivalry has slowed down the pace of BCIM.

Dhaka needs to employ its diplomatic apparatus to integrate with China and other Southeast Asian countries, taking the institutional advantages of OBOR in general and BCIM in particular. Dhaka and Beijing should work closely to find ways for Bangladesh to access the most dynamic region of the world, i.e., East Asia, through Myanmar, taking advantage of China's leverage over the country.

China's plan to revive the Maritime Silk Route (MSR) and development of economic belts offer immense opportunities for Bangladesh. The plan of the 21st century MSR coincides with Bangladesh's demarcation of its maritime boundary with two of its Bay of Bengal neighbours—India and Myanmar. This gives the country an opportunity to build a blue economy in the world's largest Bay.

It is expected that both Dhaka and Beijing will forge greater cooperation involving blue economy. According to the Sino-Bangladeshi Joint Statement, the two countries will also commence feasibility studies on the establishment of the China-Bangladesh Free Trade Area and China will continue to support Chinese enterprises in the construction of special economic and industrial zones in Bangladesh.

The two parties also affirmed that, in addition to Chinese domestic banks, the AIIB will be an important financial source for Bangladesh's economic development needs, as witnessed by the fact that one of the first four AIIB loans was for a Bangladeshi power distribution system upgrade and expansion project.

China already has FTAs with a handful of countries, including Pakistan, as well as with ASEAN. China's FTA practice is evolving, and its existing agreements provide a reliable indicator of the extent of trade and investment facilitation and liberalisation we can expect under the future China-Bangladesh FTA.

Conclusion

China has always believed in mutual respect and treating each other as equals, and advocated mutual accommodation and dialogue among civilisations. Despite their differences in national condition, development stage and cultural background, all participants of Belt and Road are equally important partners. All the Belt and Road projects must be open and transparent, and should be aligned with the development strategy and long-term plan of the participating countries. Flexibility to and fully accommodate the reasonable concerns of all parties in the spirit of seeking common ground, respecting differences and pursuing common prosperity are essential.

The partners must be transparent and corruption free, which is also beneficial for China. As long as China is not tone-deaf and is able to take effective steps to correct the problems, it will have a good chance to succeed. China, for example, may set up a mechanism to review current and future projects, which will enable it to continually refine its policies and practices so as to bring greater transparency, open competition, inclusive growth and wider acceptance overseas. Going forward, China's door will open even wider, for this serves our own interests as well as those of others.

Dr Salehuddin Ahmed is Professor, BRAC University, and Former Governor, Bangladesh Bank.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments