Is there a way out of the ethno-political cauldron in India’s far-east?

Ever since I read The Bengalis: A Portrait of a Community (Rupa Publications, 2017), I have been on the lookout for nonfiction books written by Sudeep Chakravarti. What attracted me towards his approach to nonfiction is not only the vast array of research materials he brings on the table but also the way he combines research with creative nonfiction and then tells the story in his uniquely flowy yet punchy manner. But when Sudeep's The Eastern Gate: War and Peace in Nagaland, Manipur and India's Far East (Simon & Schuster, 2022) landed on my desk, I was faced with a dilemma. While his previous books fall well within my areas of interest, I can't quite say the same about this one.

It was the lingering taste of The Bengalis that made me skim over the first few pages. After describing why this region is India's gateway to realising its eastern ambitions, Sudeep soon cuts to the chase, stating that the Naga peace process is central to establishing peace in Nagaland and Manipur, and "to a lesser extent, to Arunachal Pradesh and Assam." His aim is to look at options for working out a viable peace deal which does not rise and fall in sync with the government's "Look East" or "Act East" policy but which sees "things from the perspective of this region".

With a quick reference to Irom Sharmila, Bengali fiction writer Mahasweta Devi and Meira Paibi leader Yumnam Mangal Devi, he then incorporates the women's angle into the narrative, which is often lost when accounts of history and geopolitics are written by men. The groundwork thus laid, I was rather intrigued.

Throughout the book, between sections of a chapter, there appears in italics what Sudeep calls in a note at the very beginning "a 'dispatches' element", which weaves into the narrative "news breaks … information and messages received and exchanged, notes, and thoughts as preparatory to writing …" This element adds a unique flavour to the book, often assuming a satiric tone, the kind of which I have yet to encounter in a nonfiction work of intense deliberation.

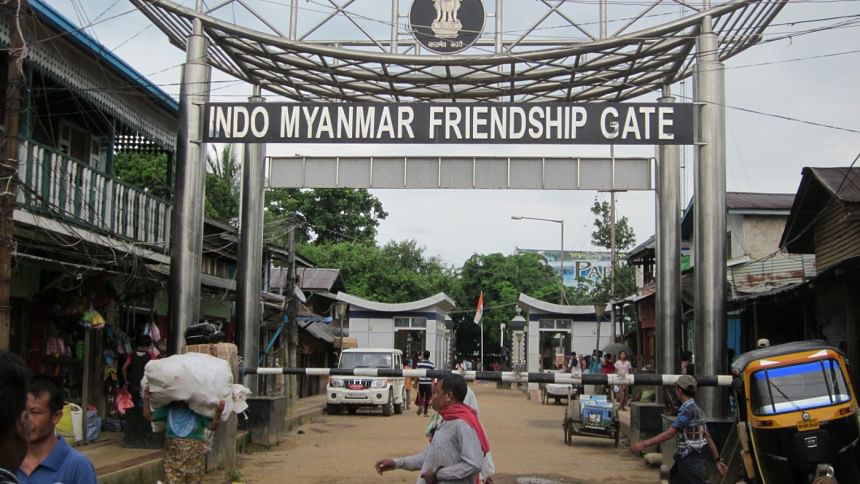

Moreh's dark underbelly

As the first chapter begins with a mysterious arms dealer who displays the author a collection of various weapons, Sudeep's prowess in narrative nonfiction becomes evident. It is as detailed as a journalist's, as thorough as a researcher's, and his storytelling is as literary as a fiction writer's. From the mysterious dealer, Sudeep takes us into the bowels of Moreh's dark underbelly. Moreh is the conduit for arms, drugs, contraband, and other smuggled products to flow between India and Myanmar and China.

While sharing details of interviews with security personnel about the narco trade, he writes: "They pointed to the involvement of at least a dozen rebel groups of all ethnic persuasions such as Naga, Meitei, Kuki, and Zomi, active in Manipur; and that of the political, bureaucratic and security establishments. All feed off the narco economy. All want to control it. All find some accommodations, find a level."

Providing missing links through a creative approach

As I traversed this vast terrain, I realised that the issues plaguing the region have hundreds of political and historical ramifications. The ethno-political situation is combustible and has always remained so since the 1940s. Ethnic groups with some clout derived from their "demographic heft" have their own rebel groups that, by default, are pitted against rebel groups of other ethnic persuasions. For example, the Meitei and Kuki rebel factions are at war with the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), especially with the NSCN (I-M). In many cases, one ethnic group has several factions that are fighting each other to a bitter end. Consider the deadly battles between NSCN (I-M) and the breakaway faction NSCN (K). The instance of CorCom, a unifying platform for seven Manipuri rebel groups, is an exception which has materialised only because all the various factions, including those from Naga and other ethnicities, had to form an alliance to fight against the NSCN (I-M), India's second largest rebel group after the Communist Party of India (Maoist). So, CorCom was more like an existential call than an intellectually mediated decision to establish peace.

As the "dispatches" demonstrate, Sudeep knows this terrain as intimately as one knows their hometown. Just like a master storyteller unravels the different interconnected stories in a novel, Sudeep unpeels the issues underlying the multi-layered conflicts in this region. As Sudeep walks the reader through this region, it is only likely that they will encounter missing links with political ramifications multiplying. At this juncture, what I found to be most remarkable is that Sudeep consciously does away with a chronological approach; he rather combines dispatches, interviews, creative nonfiction, analyses and research in a non-chronological way that provides all the missing links in addition to making one want to know more about the future developments.

The centrality of AA and FA

Ultimately, it all boils down to the Alternative Arrangement and the Framework Agreement. AA revolves around the erosion of protection for the Naga people (and their rights over their lands) living in the hill districts of Manipur. Such protection, usually guaranteed for tribes in other NE states, was not provided to the Naga tribes in Manipur. NNC activists perceive the tightening of Manipur government's administrative control over the Naga people and their lands as a well-designed "Meitei conspiracy", and it turns out that this perception is not unfounded at all.

Although the AA came to naught, the Framework Agreement (FA) came to fruition in 2015 when a BJP-led alliance assumed power in India in 2014. The FA was signed in 2015 between the Government of India and the NSCN (I-M) with the aim of putting an end to conflict with Naga rebels and finding a solution to ending "an uneasy ceasefire with I-M signed in 1997". It wasn't long before it became obvious that the FA was one more piece on the region's "game of chess". The BJP-led government was playing it to its advantage, using it to push its communal, Hindu-majoritarian propaganda during election times. The NSCN (I-M), on the other hand, held rigidly on to its demand for a Greater Nagaland, a demand which was eyed suspiciously both by the government as well as other rebel factions.

The AFSPA

Sudeep traces the genesis of the ethno-political conflicts to the period of British colonial rule. But all the successive governments since India's independence, his research shows, have contributed even more to aggravate the situation. It did come as a surprise that the Armed Forces (Assam & Manipur) Special Powers Act (AFSPA), the harshest of laws, was passed as a bill in the parliament in 1958 when Jawarlal Nehru was India's prime minister. The heavy-handed use of this law gave a free rein to security and paramilitary forces to carry out extrajudicial practices, including killings, torture, rape and enforced disappearance, in Manipur and Nagaland, targeting mainly the Meitei and Naga rebel groups.

Threats posed by migrant influx

It is towards the end of the book that Sudeep steers his focus on the issues of internal migration in pre-partition India and migrant influx from neighbouring countries, mainly from Bangladesh. With the meticulousness of a historian, he, again, traces the root of the migrant issue to colonial times when large numbers of Bengali Hindus had migrated to Assam either as professionals to work in the British administration or as agricultural migrants. Then came India's partition which triggered communal riots all over India and Pakistan, forcing millions of Muslims and Hindus out of their homes. Millions of Bengali Hindus from what then became East Pakistan (later Bangladesh) fled to West Bengal, Tripura and Assam. This influx created tension in all these states but things got especially incendiary in Assam. When Assamese was made the official language of Assam, protests broke out on both sides of the ethnic spectrum and violent attacks were carried out on Hindu Bengali settlers.

This already-incendiary ethno-religious mix was exacerbated by the influx of economic migrants from Bangladesh, known as IBIs, or Illegal Bangladeshi Migrants. Two examples suffice to show the extent to which the ethnic-religious fires flared up, killing and evicting Muslims who had been living here for hundreds of years as well as the IBIs. The Nellie Massacre happened in Assam in 1983 that "killed over 2,100 Bengali Muslim men, women and children …" Referring to Sanjoy Hazarika's book, Sudeep writes that "in the early years of the rebellion Bodo militants walked in from camps in Bhutan and simply machine-gunned Bengali-speaking Muslims".

This chapter, titled "Migration Matrix: The Future Will Be Tense", is hugely important and relevant to the current political context of India where Muslims are being demonised along religious lines, where the IBIs are regularly facing violence, and the Bengali-speaking Indian Muslims are collated as IBIs and "are doubly victimised for their language and religion, with even their citizenship called into question," as a recent Scroll article points out with reference to events in Delhi's Jahangirpuri area.

The situation was further complicated by the BJP playing the NRC and CAB, later CAA, to legalise non-Muslim migrants and strip IBIs or Muslims of Indian citizenship.

But what if a climate disaster strikes along the coastal belt of Bangladesh? What if Bangladesh fails to ensure sustained socioeconomic growth? India will be powerless to stem migration from Bangladesh arising out of such situations, Sudeep writes. The picture he paints of such a future is bleak, if not dystopian. Sudeep's forecasts, needless to say, are predicated on facts and figures. His prediction that Bangladesh's failure to make socio-economic progress will result in more migrant influx into India rings true. It will mean more instability in the region. He does not lose sight of Bangladesh's strengths though and aptly points out that Bangladesh has stopped being a haven for rebel factions from India's Northeast, thanks to the Sheikh Hasina-led government. But he seems to place the onus on Bangladesh to control the influx and thus save the region from this impending disaster. I am not as perspicacious a commentator as Sudeep is. Nor am I an expert on the geopolitical affairs of the region like he is. Even so, as a journalist and writer who takes an interest in the history and the current cultural and political trends of what is now known as South Asia (SA), I can't help commenting on this.

Sudeep balances out the bleakness of the future by painting a bright picture where Bangladesh has made significant strides in socioeconomic progress. This progress, Sudeep hopes, will adequately address the livelihood needs of people, precluding them from slinking into India through the porous border. It is highly unlikely that this is how things will pan out. Neither India nor Bangladesh is a model for economic development. The administration in Bangladesh is as corrupt and morally bankrupt as it is in India. The saga of GDP growth sounds more like a myth than a reality. Of course, there are success stories in the garment industry, remittances and the private sector but what trickle-down benefits are there for the increasing number of poor people in urban areas and villages? Anyone living in Bangladesh knows that prices are higher in Dhaka than most other metropolitan cities in South Asia and that inflation rates have already gone through the roof.

Bangladesh's poor economic performance is also conditioned, at least in part, by geopolitical factors. The current Sheikh Hasina-led government, ever since it assumed power in 2009, seems overzealous to curry favours with India's government. It has given its big neighbour many commercial concessions and it continues to be India's biggest market in South Asia. Yet the trade deficit with India is still huge. On the political front, India's big brotherly attitude has for long caused many humanitarian crises across SA, a point also emphasised by commentators in Nepal. The brutalities of the BSF along Bangladesh-India border are a case in point.

So, if Bangladesh's poor economic performance is causing an influx of migrants, it is most likely to continue.

The onus, therefore, is as much on Bangladesh as on India, simply because refugees—whether they are displaced forcefully or for economic and climate change-related reasons—cannot be blamed. Instead of a heavy-handed approach, perhaps a more humane approach to the refugee issue is the first step.

This is the only point that I had an alternative thought about.

All the other points are dealt uniquely with a creative approach that combines several disciplines and marks a rare achievement in the genre of nonfiction. Whether one is interested in partition history or this region's geopolitics or more particularly, about the Northeast, they will have to consult this book, which, most definitely, will provide them with all the details, data, perspectives, and analyses they perhaps need to know.

Rifat Munim is a writer, editor, and translator based in Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments